Revisiting the March on Washington

On the afternoon of August 28, 1993, the heat and humidity in Washington, D.C. were overwhelming. I had spent the morning photographing on assignment for the United Auto Workers (UAW) magazine Solidarity. Autoworkers from around the country were attending the thirtieth anniversary of the march that precipitated the "I Have a Dream" speech that Martin Luther King gave in 1963 from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial — a speech that galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

Among the photos I took that day at the 1993 commemoration of the speech was one of Raymona Middleton, a third-generation Washingtonian who in 1963, at the tender age of 13, had begged her mother to let her attend the march to hear King speak. Recently, while going through my papers, I came across the letter Ms. Middleton wrote to me in December of 1993 after I sent her the pictures I had taken of her at the thirtieth anniversary. Her letter described that day in 1963: "My mother, expecting trouble, forbade me to attend. No amount of pouting or tears changed my mother’s mind. I had to stay home watching it all on television."

She wrote of her motivation to be present at the first march: "I, like millions of Americans, even as a young teenager, had seen on TV the horrific violence throughout Alabama, Mississippi, and other parts of the Deep South towards African Americans! Some of these TV broadcasts showed police attack dogs and local firefighters using water hoses on the marchers, people being dragged through the streets like trash. So, by age 14 I had an awareness of severe racism towards people who looked like me. I remember what happened when police, and state troopers killed and severely injured not just Black folks, but many white students who had emerged from the North to travel south encouraging Voting Rights. In 1965, two years after the original MLK March on Washington, the violence continued towards Lutheran clergy, Jewish rabbis, and Catholic priests during the March from Selma to Montgomery, better known to me as 'Bloody Sunday.'"

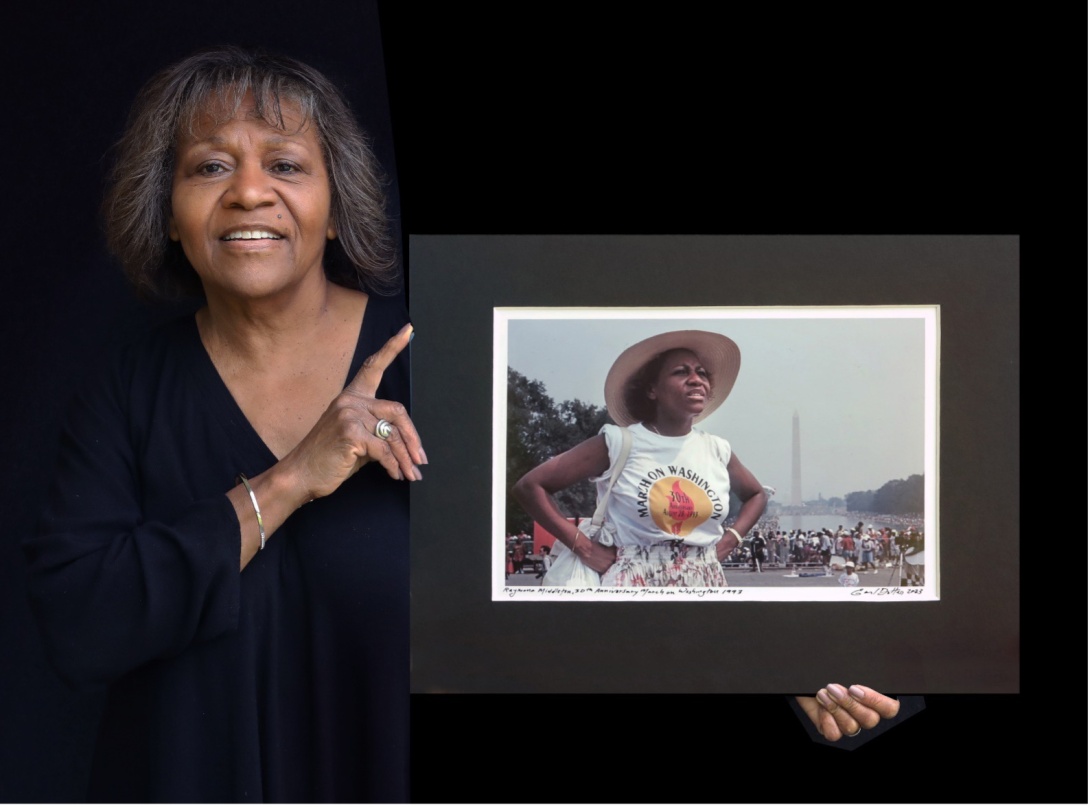

Raymona Middleton, photographed by Earl Dotter this year.

Finding Raymona Middleton's 1993 letter inspired me to try to locate her this past spring. After three decades, I was able to find her current phone number and gave her a call. She quickly recalled that day in 1993 at the Lincoln Memorial and the photos that I had taken of her. She told me that she had saved the page in Solidarity magazine that featured her photo, and had framed and hung it in her home, where it still hangs. I learned that the original photos I had sent her long ago had been lost during a move, so I arranged to make a home visit to give her replacements.

I also asked Ms. Middleton if I could update her portrait while she held some of the photographs I had taken of her during the August 28, 1993 thirtieth anniversary march. I wanted to show that her life still stands out today.

Raymona Middleton is a woman of faith who has imbued her life with social purpose. Often, she has been inspired by the pastors at her church, Rev. Dr. Grainger Browning and Rev. Dr. JoAnn Browning. It took two weeks before we could arrange a convenient time for me to stop by her home in Charles County, Maryland. During that time, I began to get a clearer idea of all the socially useful work that continues to occupy her time these days.

Finally, late this past May, after she had spent a day as part of an Outreach Team of women from her church with patients at DaVita Dialysis in Oxon Hill, Maryland, we arrange

(Left) Ms. Middleton holding a poster commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery march. Next to her are the pair of cowboy boots she decorated to remember her experience living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo by Earl Dotter. (Center) The framed page from Solidarity magazine in Ms. Middleton's home. Photo by Earl Dotter. (Right) Ms. Middleton gave Shawn Gibson, a dialysis patient who has suffered vision loss, a set of Bible CDs after they got acquainted while Ms. Gibson was receiving treatment at the clinic. Photo courtesy of Shawn Gibson.

Ms. Middleton recounted how her dad, Raymond, survived the Normandy Beach German gunfire as the Allies invaded Europe during World War II. But he

"My Dad, like many vets still today, signed the papers, he put on the uniform, and he risked his life for his country......but then got no help from the Veterans Administration," she said. "Like so many others his sufferings from war were real. I wanted to honor him and his service to our country at the thirtieth anniversary MLK March that I finally was able to attend."

As an adult, Ms. Middleton became a Federal Civil Servant at the GSA level in multiple agencies, the last of which was the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), retiring in 2005 after 33 years. She mentioned that while she was working at the U.S. Department of Interior, she made use of her 15-minute morning coffee breaks distributing her homemade sandwiches to the homeless encamped near that government building.

I asked about the colorfully painted cowboy boots displayed on the porch next to her. She explained that after retirement, she moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. The decorated boots are a remembrance to her enjoyable years there — but when the pandemic hit, she felt the need to return home to Maryland. Out west, she had developed an appreciation for the African Americans who had made their way there during the Great Migration that began after the Civil War, some forming Black townships and becoming cowboys and horse trainers.

Raymona Middleton holding a photograph of herself taken by Earl Dotter at the 1993 March on Washington. Photo by Earl Dotter.

That conversation led Ms. Middleton to convey some of her own family genealogical history. That research revealed that her maternal great-great-great-grandparents — Jacob Richardson, born enslaved in 1795, and his wife Mariah, born in 1837 — were both emancipated in Queen Anne County, Maryland, according to the 1860 census. Her paternal great-great-grandparents — John Alexander, born in 1801, and his wife Hannah Alexander, born in 1805 — were listed in the 54th District, Russell County, Virginia in the 1850 Census as "Free Inhabitants - Mulatto Farmers."

She said, "I believe that Dr. King, like most of us, would be discouraged by the current political status of our country. Back in January 2014, I decided to have DNA testing. To my surprise, the outcome was that I'm a total mix of everybody: (I'm 90%-African, 1%-Native American, 1%-Asian, 7%-European [Irish/Finish/Iberian], 1%-Caucasian = 100%). Most importantly, I am a true American, and I'll tell you why.... from both my maternal and paternal grandfathers to my own father as well as my son Robert have all fought in the military to protect and defend these United States of America. I am still searching, but yet to find supporting documents of a Civil War Patriot in my lineage. I am a descendant of former slaves who helped build this great country of ours, and feel that their blood, sweat, and tears are still crying out from the ground we walk on for equality and justice for all!

“For over 400 hundred years of being bought and sold like furniture, my ancestors toiled in inhuman conditions, building the White House brick by brick and serving within it, to becoming the human engine of our nation’s economy, growing and harvesting cotton, tobacco, and rice, a 'direct source' of vast riches still being inherited by others today. Like Dr. Martin Luther King, and those who marched with him, I still have his same Dream today, sixty years later!"

Tags

Earl Dotter

Earl Dotter is a longtime photojournalist who has dedicated his career to documenting the American worker. Many of his photographs appeared in Southern Exposure, the magazine published by the Institute for Southern Studies.