Gene Nichol on North Carolina's lessons for America's democracy struggle

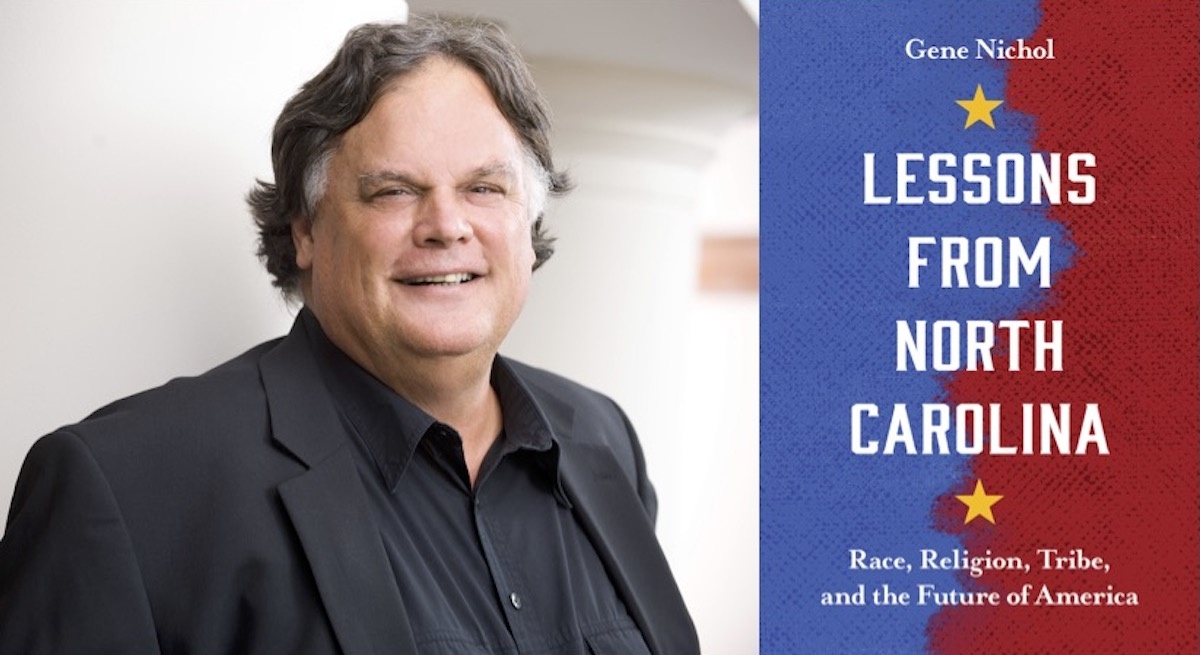

Gene Nichol, a UNC law professor and anti-poverty scholar, recently spoke with Facing South about countering the systematic assault on democracy in North Carolina — the topic of his latest book.

North Carolina, a state once considered a beacon for progress in the South, has in recent years become synonymous with regressive politics that are undermining democracy and diluting the influence of the state's increasingly diverse electorate. The North Carolina Supreme Court's new Republican majority solidified this anti-democratic takeover in a trio of decisions issued late last month that allow extreme partisan gerrymanders, restore a restrictive voter ID law, and make it harder for people with felony convictions to regain their voting rights.

Facing South recently spoke about what's happening in the state with Gene Nichol, an anti-poverty scholar, law professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and author of the new book, "Lessons from North Carolina: Race, Religion, Tribe, and the Future of America." The conversation touched on the history of political division and progress in North Carolina, the backlash against the state's diversifying electorate, and the power of movement politics to secure democracy.

Nichol previously served as a dean at UNC, law dean at the University of Colorado, and president of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. Nichol took part in the Moral Monday movement protesting the Republican-led North Carolina General Assembly's regressive agenda, and he authored a series of op-eds for the News & Observer condemning legislative assaults on the poor and charging that the GOP ruled as a "white people's party." He also directed the UNC Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity, which was created in 2005 during Nichol's tenure as the law school's dean. The position allowed him to travel to communities across the state to learn from poor North Carolinians about their lives.

In 2015, despite forceful opposition from students and faculty, UNC's Board of Governors, selected by the General Assembly, voted to close the Poverty Center as well as the Institute for Civic Engagement at historically Black N.C. Central University and East Carolina University's Center for Biodiversity. As UNC law school dean Jack Boger said of the poverty center's closure, "The recommendation rests on no clearly discernible reason beyond a desire to stifle the outspokenness of the center's director, Gene Nichol, who continues to talk about the state's appalling poverty with unsparing candor."

In place of the Poverty Center, Nichols helped the UNC law school develop the North Carolina Poverty Research Fund, which continues to examine the systemic reality of poverty across the state. In 2018, he published "The Faces of Poverty in North Carolina: Stories from Our Invisible Citizens," which focuses on individuals struggling with economic hardship. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

One passage of your book notes that "the state of North Carolina had long been regarded as a leading edge — perhaps the leading edge — of progressivism in the American South." But you also note that "since 2011, North Carolina has experienced a powerful Republican revolution." Can you speak to this duality and how it continues to shape the state's political landscape?

One way to put it is for a time, even though I think this was overdone, North Carolina was regarded as a moderate beacon in the South, different than some of our Southern state compatriots. And there was some truth in that, but now that's much altered, certainly since 2010. I think that the way The New York Times describes it, we have become a "pioneer in bigotry." There are a lot of different components of that, and this book is about a lot of them. And it concerns some lessons to be learned from the revolution which has taken place in the last 13 years in North Carolina, not all of which are heartening ones. So, I think broadly speaking, the country is engaged in a powerful struggle for democracy now, and North Carolina is as well.

I think it's fair to say that we've been at it a little longer than most of the rest of the country, so we've got a little more experience in it. So it's probably worth thinking about how a number of these issues have played out here. But the country as a whole, certainly since the Trump years, is now engaged in its most important struggle for democracy itself. And we've been heavy participants in that unfortunate reopening of some of the fundamental values of the United States in North Carolina.

You note the "backlash" that occurred in North Carolina after the election of the first Black president in 2008, which ultimately led to the all-white Republican control of all three branches of the state government. How are racism and racialized political maneuvering undermining the will of the state's increasingly diverse electorate?

When you look at this broad array of changes, it can be hard to tell where to start. I remember Lily Tomlin used to say, "No matter how cynical I get, I can't seem to keep up." And it feels a little bit like that in North Carolina. But actually, consistent with your question, we almost always know where to start in North Carolina, particularly when it comes to challenges to democracy or the effort to crush full democratic participation; those always start with race. And they have throughout our history, really — our first day as a colony till this very morning.

We witnessed this potent backlash to the electing of Barack Obama: change in government, change in party leadership on really all three branches of government, at least for a time. And that reflected some astonishing changes that weren't talked about as much. For one thing, we have been governed since 2010 in the North Carolina General Assembly by Republican caucuses that have, for the most part, been all white — literally all white.

And that's an astonishing thing to contemplate. The 14th Amendment passed over 150 years ago. And when our folks in these last 13 years have gone into their caucuses, their closed caucuses, to decide what the policies are for North Carolina, they have essentially been an all-white conclave. And it's not just a question of aesthetics; they have governed like a white person's caucus. To go through the list: The federal courts have told us that this General Assembly, the Republican General Assembly, has given us the largest, most pronounced racial gerrymanders ever presented to a federal court. They have attacked the right to vote of African Americans in North Carolina with "surgical precision." That's the words they use and found repeatedly. They have embarked upon the boldest, most blatant examples of political gerrymandering ever seen in the United States.

They repealed the Racial Justice Act [addressing racial discrimination in seeking or imposing the death penalty]. They reacted to the Black Lives Matter movement by making it harder for folks to get a hold of police cam video. They have passed laws of late designed to punish what they characterize as rioters, but basically meaning, too frequently, Black demonstrators, while they've welcomed white protesters with AK-15s strapped over their shoulder. They're telling us what we can learn about our racial history in the public schools, these folks who sit as a white people's caucus. They have lionized Confederate monuments, explaining as they did it that the Civil War wasn't really about slavery, it was about Northern tariffs.

So, the long and short of it, then, is that they not only have looked like a white people's caucus, they have governed like one, and have wounded North Carolina dramatically in the process.

For years you have been a crusader against poverty and systemic inequality, which has made you a target of the state's Republican leaders. In the book you argue that poor North Carolinians are not viewed or respected as "entire citizens" and have been excluded in the governing decisions of the state. Can you talk about how poverty functions as an obstacle for the full expression of democracy?

I guess the most obvious manifestation of that is since 2010, in North Carolina, we've embarked upon what's accurately described, I think, as the stoutest crusade against poor people by any modern state in America.

We, of course, first and foremost, for whatever it is now, 13 years, have denied Medicaid expansion. I'm praying hope against hope that that is about to be changed. But that's 13 years in which we have turned aside billions of health care dollars directed at low-income Tar Heels. That's 600,000 people a year denied access to health care. As the studies have found, it's meant that 1,000 or more Tar Heels every year died simply because the legislature wouldn't expand Medicaid. And they couldn't for the life of them explain why. That's because the actual reason was that they didn't want to give credence to any program that was associated with Barack Obama. That's one thing you can decide politically, but to decide you're willing to let a thousand of your sisters and brothers die just in order to make that political statement is an astonishing one.

But the list is much longer. They ushered in the greatest cut to a workers' compensation program in American history, taking us from the middle of the pack to having the stingiest workers' compensation program in the United States, which is where we still are, and which of course made it more difficult to deal with the challenges of COVID. Think of the impact of those two things, the refusal to expand Medicaid, which meant the stress on our health care system was dramatically increased, and then so many thousands of North Carolinians losing their job. And they had to deal with that brutal set of changes through the worst unemployment compensation program in the country.

We became the only state to ever abolish or repeal its earned income tax credit. And that meant that working families in North Carolina making about $35,000 a year actually had a tax increase as a result of the repeal of the earned income tax credit. They changed our tax scheme dramatically, making the income tax flat and then reducing it for folks at the top, and notably increasing sales taxes across a broad array of fronts. And they did so acknowledging that that would result in a heavier tax burden for people at the bottom, and that's a huge part of what their rationale was. They ended the state's modest appropriation for legal services. They dramatically cut dental services in the public schools, which of course impacts low-income people. They cut food stamps repeatedly, even though it didn't save us a penny in North Carolina because the food stamps are paid for by the federal government. But we were so anxious to make sure that even the federal government didn't put any money into the pockets of our poorest Tar Heels that we opted for those changes. We've from time to time cut the modest allocations that the state has had to food banks.

You put all that together, and they have treated low-income people as if they weren't part of the commonwealth — it's as if they were strangers to the constituency — and behaved in ways that you simply couldn't explain if they thought that poor people actually counted in the process.

But that's a big indication of the theme, it seems to me, of the North Carolina General Assembly in the last 13 years, whether it's in race or in poverty or in religion or in sexuality, for example. I think their common theme is that some folks count and others don't, or some folks count a lot more than others do. Some of us are the real American tribe, and the rest of us are like trespassers, or we're allowed at the sufferance of the traditional majority. And if that is inconsistent with demands of our constitution and our creeds, then we've increasingly said, "Well, the constitution and those creeds are going to have to give way. We believe in democracy only so long as we win." That is, here, sort of the white Christian male, traditionally empowered folks. We believe in democracy only so long as they win. We believe in equality only so long as their ascendancy is guaranteed. So that means that things like equal justice under law have to be now swallowed with a defining and defeating asterisk in North Carolina.

You write that "after a lifetime of study and engagement, I find it hard to place meaningful confidence in the courts, state or federal." I think about the recent anti-democratic decisions from the North Carolina Supreme Court. How do we best advocate for multiracial democracy in such a hostile political landscape?

That's the million-dollar question, I guess, isn't it? But first, let me back up a little bit.

It should be said, first of all, that North Carolina has benefited a good deal in the last dozen years from some of the traditions of independent federal judicial review. A lot of the worst excesses of this legislature — the racial gerrymandering, the monster voter suppression laws, and the like — have been declared unconstitutional by the federal courts, reminding us of the need for independent federal judicial review. But anyone who watches the unfolding of the United States Supreme Court now in Washington, D.C., can't have any sense that they will be potent guarantors for fundamental human rights. Quite the opposite. The question is going to be, how much damage are they going to do to central human rights and liberties?

You mentioned an array of decisions which just came down here at the end of the last month by the North Carolina Supreme Court. They decided that they were going to be all in in support of partisan gerrymandering. They decided that they were just happy enough with a racially tinged voter ID requirement. And they were quite content to disenfranchise, what, 55,000 folks who in North Carolina had served their sentences but were still under some court supervision, overturning the decision below. Those are massively unfortunate rulings, if we remember that the right to vote is the most fundamental of all rights and said to be protective and a guarantor of all other liberties.

I've studied those new decisions a little bit, and they seem to be announcing a sea change, saying in effect that the North Carolina Supreme Court is now going to be a willing and happy partner to the crusade against democracy which has been waged by the North Carolina General Assembly for the last 13 years. So that's an immensely distressing turn. So, I don't think that we can have confidence that our democracy is going to be saved and resurrected through the recourse to the judiciary.

And in my own view, it's hard to have a complete faith sometimes in the traditional give-and-take and incrementalism of the Democratic Party. So, to the extent that there's confidence to be had, I see it in the movement politics of North Carolina.

In a recent newspaper op-ed you wrote about "green shoots of democracy" popping up across the South and the country. What keeps you optimistic about the possibility of multiracial democracy in North Carolina and elsewhere?

There are green shoots appearing across the country now from the activism of engaged citizens. You have the abortion vote which took place in Kansas, which stunned both Democratic and Republican politicians. By significant margins people in Kansas stood up and said, "We're not going to allow our rights to be taken away." You have this marvelous Supreme Court election in Wisconsin, which reflected the same thing.

I think four of the last six presidential elections in Wisconsin have been decided by less than a percent. But this progressive liberal justice running explicitly on abortion rights and securing democratic government, she won by I think 11 points in ways that no one assumed. You have those marvelous, inspiring legislators down in Nashville, standing down the worst aspect of traditional Southern politics, and doing it in a way that just lifted the nation. There's this young trans woman from Montana of all places who rebuked the legislature and, it seems to me, came forward as a far more potent representative of the American promise and tradition than her adversaries in the statehouse. And then the Moral Monday movement has been such a potent example of people-based, engaged politics here in North Carolina. I think it's had a dramatic impact on our political fortunes.

So my own sense of optimism comes more from this movement politics than it does from a lot of the traditional fora. But I think it's a powerful basis for hope, even in what are obviously dark times, when we face a threat to our democratic institutions unlike anything that we have seen in many generations. And I'm not sure we always understand that in North Carolina, but we ought to. We ought to be getting used to its presence, so that we face a challenge to what we stand for as a people, what kind of commonwealth we actually choose to be. Whether we're still going to believe in the American promise, or, like many folks, unfortunately some of whom are in leadership positions, whether we're willing to give way in favor of their own desire to accumulate power.

It's easy to understand how we can principally think of ourselves as just the heirs of freedom, that there was all this great work done, but it was in the past and democracy is kind of assured for us. But as we know in North Carolina, it's not. It has also been threatened time and time again in this state. And it's not going to be anyone but ourselves who are going to assure it. Democracy is, as Robert Kennedy said, I think, "never a final achievement. It is a call to unending struggle." And that's a struggle that we face in North Carolina right now, and that we are in potent jeopardy of losing.

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.