Who gets to rest in peace? The complications of repatriating remains for Southeastern tribes

This 2002 photo shows artifacts stored at the Research Center of the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology. The office, which is housed in the state’s Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, holds the second-largest number of Native American ancestral remains in North Carolina. (Photo via North Carolina Digital Collections.)

On a Saturday afternoon in late March, a small group of Native American tribal members gathered at an auction house in rural Mebane, North Carolina, protesting the sale of a 600-year-old human skull. Local law enforcement had been made aware of the auction just days prior but determined that the sale didn’t violate state or federal law, as reported by The News & Observer. The day before the planned sale, however, a member of the state’s Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation created a TikTok video that drew thousands of views, fueling outrage and demands to pull the skull from the auction.

Tribal members were ultimately able to halt the sale of the skull, and its owners have since indicated their interest in repatriation. But the incident underscores complications surrounding protections for Native American burial remains in Southeastern states.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) passed by Congress in 1990 sets out a process for federal agencies and museums that receive federal funding to repatriate cultural items — including human remains and funerary objects — to Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. But the landmark legislation doesn’t apply to tribes without federal recognition, leaving many in the Southeast — most of which have only state recognition — to the mercy of institutions that may or may not be willing to engage them in the repatriation process while grappling with laws that vary from state to state.

More than three decades after the passing of NAGPRA, hundreds of thousands of Native American remains have not yet been returned to their descendants or laid to rest but instead are locked in storage facilities and research labs across the country. For example, the Tennessee Valley Authority, a federally owned electric utility corporation, maintains the largest collection held by a federal agency. The agency only recently completed a NAGPRA inventory of the remains of nearly 5,000 Native Americans it removed from Alabama, Tennessee and Kentucky, with repatriation set to begin later this month.

Of the institutions and museums that hold the greatest number of Native American remains in their collections, several are located in the South, where a legacy of settler colonialism and forced migration shapes the politics of tribal recognition — and thus access to NAGPRA protections.

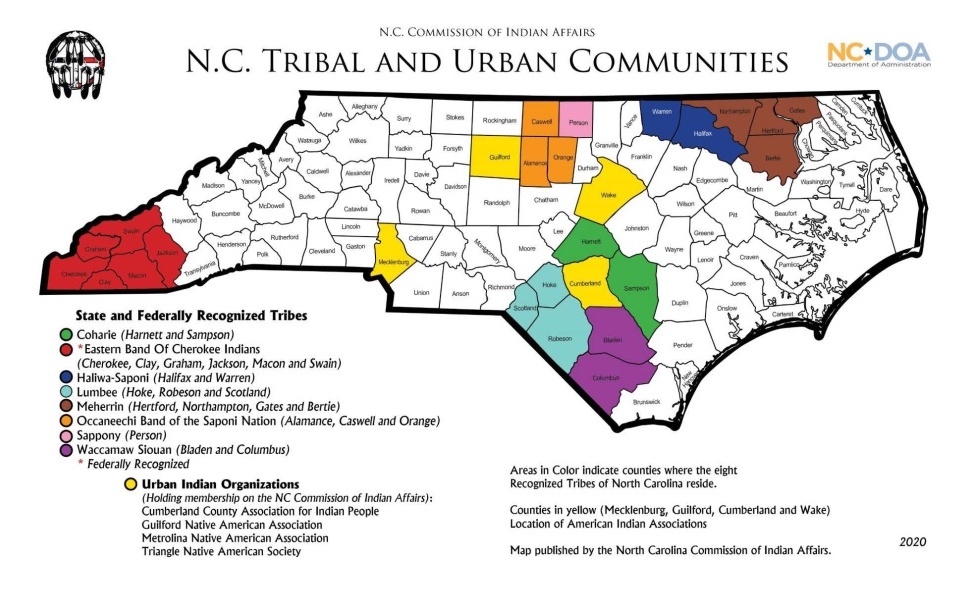

Greg Richardson serves as executive director of the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs, which represents a dozen Native American groups across the state with the highest population of Native Americans east of the Mississippi River. He describes NAGPRA as a “creature of the federal government and federal legislation.”

“As I view it, there's a real disparity here, in terms of the way that human remains are addressed state by state,” Richardson said.

When laws conflict

According to The News & Observer, the skull from the Mebane auction is believed to be that of a young girl, with the owner having purchased it from an antique store in Montreal in the 1960s. The timeline of the sale and the skull’s potential origins with First Nations in Canada pose complications, since it may not be from tribal or federal lands where NAGPRA applies in the U.S. But in North Carolina, the sale of any human skeletal remains taken from unmarked burial sites is still illegal under the state’s 1981 Unmarked Human Burial and Human Skeletal Remains Protection Act.

Other Southern states including Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Tennessee have similar statutory protections. But there have been times when federal and state law have come into conflict, such as a 2008 case brought by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation over remains disturbed by a construction project on private property in the Chattanooga area. It eventually led the Tennessee Office of the Attorney General to publish an opinion in 2011 declaring instances when NAGPRA preempts state statutes on the reburial and display of Native American remains.

North Carolina formally recognizes eight tribes, but only one of them — the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who live on the Qualla Boundary in Western North Carolina — is also federally recognized. One of those state-recognized tribes, the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, maintains an office in Mebane, where the skull was to be auctioned. But neither the Occaneechi nor the N.C Commission of Indian Affairs was consulted regarding the sale’s legality, Richardson noted.

“But I’d have to think that that was partly because you're dealing with people who really do not know and understand the lay of the land for Indian tribes,” he said.

Richardson, who is a member of the state-recognized Haliwa-Saponi tribe based in Halifax County, hopes that the Mebane case will offer a “teachable moment” for auctioneers and others unfamiliar with legislation protecting burial remains. “You don’t fix it by just ignoring it and saying, ‘Well, this is just a one-time thing, it’ll never happen again,’” he said. “It will happen again.”

Part of the solution could include strengthening language in the North Carolina statute regarding unmarked human burial remains, Richardson suggested. The recently formed N.C. American Indian Heritage Commission has also been examining ways to simplify the repatriation processes for state-recognized tribes.

The Repatriation Project Database published earlier this year by the nonprofit news outlet ProPublica shows that less than 30% of ancestral remains in North Carolina have been made available for return to tribes, which means an institution has established a connection between the remains and a tribal group. This number varies across the South, but for most states in the region — Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia — less than 50% of remains held by institutions have been made available for return to tribes.

The N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources — which the N.C. Office of State Archaeology is a part of — told Facing South that, as a state agency receiving federal funds, it follows NAGPRA guidance. The department also says it’s committed to consulting with state-recognized tribes in North Carolina and advocating to the NAGPRA Review Committee for tribal inclusion in repatriation efforts.

“[North Carolina] Governor Roy Cooper’s recent budget recommendations include funding for an additional position in our Office of State Archaeology to advance and accelerate our repatriation efforts,” a spokesperson told Facing South in an email. “We hope to have the General Assembly’s full consideration and support for this important work.”

NAGPRA revisions underway

Administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior, NAGPRA came about thanks to efforts by Indigenous activists and organizations to restore the rights of tribes to their ancestors’ remains and to enforce the protection of Native burial sites, which have a long history of looting and destruction by professional archaeologists and amateurs alike. Despite attempts by Congress to stop it, a market for cultural items stolen from graves proliferated during the 20th century, as the Washington Post reported. But the passage of NAGPRA in 1990 established formal procedures for returning cultural items, as well as criminal and civil penalties for violating the law.

“The goal of getting NAGPRA approved was just that — getting something out there that could begin to function and facilitate repatriation among tribes and museums and to put some teeth in it,” said Nancy Strickland Fields, director and curator of the Museum of the Southeast American Indian at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke and a member of the Lumbee Tribe.

Still, Strickland Fields compared NAGPRA to a sieve, where the original law didn’t catch all the complexities surrounding repatriation.

The National NAGPRA Program maintains a Review Committee, which oversees various aspects of the law, including requests from agencies and museums that want to return Native remains and cultural items to non-federally recognized groups. A key component of the law is identifying “cultural affiliation,” which it defines as “a relationship of shared group identity which can be reasonably traced historically or prehistorically between a present day Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and an identifiable earlier group.”

But ProPublica and other organizations have underscored that the cultural affiliation concept has sometimes allowed institutions to sidestep or stall repatriation by determining that items in a collection are “culturally unidentifiable.” According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), as of February 2022 the remains of more than 116,000 individuals are still held by the federal government, of which 95% have not yet been culturally affiliated to a modern-day tribe.

Affiliation can be complicated for tribes in the Southeast, a region shaped by the land dispossession and ethnic cleansing that followed passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, and Seminole people were forced from their homes and into modern-day Oklahoma because of the act, with many dying along the brutal journey that became known as the “Trail of Tears.”

The Southeastern NAGPRA Community of Practice, a group developed out of the NAGPRA Community of Practice at the University of Denver Museum of Anthropology, specifically aims to bring together various stakeholders in the Southeast to address the “feeling of disjointedness and lack of knowledge and consultation” with repatriation efforts in the region.

“The legacy of forced removal in the southeast has impacted the trajectory of relationships between indigenous communities and state entities,” the group told Facing South in an email. “As a result there are a varying number of state recognized tribes in the various southeastern states. However, each state in the United States has specific and slightly differing burial and cemetery laws that allow for varying levels of protection and preservation.”

Shannon O’Loughlin is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and CEO and attorney for the Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit serving Indian County that provides legal expertise and strategy development on issues related to cultural sovereignty and heritage. The organization holds an annual repatriation conference and has previously submitted comments to the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs about potential revisions to NAGPRA legislation.

O’Loughlin said the concept of “cultural affiliation” so crucial to NAGPRA is viewed differently under law than science. Problems arise because of how some museums leverage their power, and because of the generally poor oversight when it comes to ensuring that institutions have followed through on the consultation process with tribes.

“Affiliation under the law is a simple administrative process that requires institutions to consult and take whatever evidence is available — not to do research, not to do DNA testing, not to do any of that, but just consult with tribes to determine a reasonable relationship between the ancestor and a present-day tribe,” she said. “And there's not a single inch of ground in the U.S. and Alaska and Hawaii that's not connected to a current present-day tribe. So there's no reason why there should be anyone on the culturally unidentifiable list, unless there's absolutely no information about an ancestor.”

In the case of culturally unidentifiable remains, NAGPRA stipulates that if none of the tribal groups consulted in the repatriation process by a museum or agency accept control, the institution can transfer control to other Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations. Another option is to transfer control to a non-federally recognized tribe, but that comes only upon the recommendation from the Interior secretary.

“Instead of going through the consultation and affiliation process that you would think would be more efficient to go through, they [state-recognized or unrecognized tribes] have to go ask the secretary for approval to receive those ancestors,” O’Loughlin said. “So it's not like state-recognized tribes don't ever get access to their affiliated ancestors, it's just the Department of Interior has made it more difficult for them to do so.”

Last October, the department proposed a set of revisions to NAGPRA, which included removing the term “culturally unidentifiable” and incorporating geographic origin into the overall affiliation and inventory process.

“Changes to NAGPRA regulations are long overdue,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, an enrolled citizen of the Laguna Pueblo, said in 2021 regarding her department’s ongoing review of the act. “It is crucial that as we consider changes, we consult with Tribes and Native Hawaiian communities at each step. I’m hopeful this process will eliminate unnecessary burdens to the repatriation process and allow Indigenous peoples greater access to their ancestors’ remains and sacred items.”

According to O’Loughlin, the Department of Interior is expecting the final rulemaking to be published before the end of this fiscal year on Sept. 30.

The right to rest in peace

At the moment, there is no state law in the Southeast requiring state agencies and museums receiving state funding to abide by a repatriation process. Nationwide, CalNAGPRA stands alone in addressing gaps in NAGPRA for tribes in California that lack federal recognition by, for example, elevating tribal knowledge in the process of determining cultural affiliation.

While the GAO has admonished some federal agencies for failing to comply with NAGPRA, other institutions undertook internal evaluations after being approached by federally recognized tribes. Among them was the Alabama Department of Archives and History. In 2018, the ADAH — which has in its possession the remains of over 100 Native Americans and more than 4,000 associated funerary objects — determined it was not compliant with the law and began the consultation and inventory process. Last August, the agency also pulled funerary objects from display.

"These ancestral remains were removed without consent," said Kellie Bowers, NAPGRA coordinator for ADAH. "Everyone deserves the right to rest in peace. We recognize here at the Alabama Department of Archives and History that it was wrong for these ancestors to have been removed. We are committed to respectfully returning these remains and their belongings to our tribal partners through the NAGPRA process."

Per federal law, the ADAH is currently engaging several federally recognized tribes with historical connections to Alabama, Bowers said. But the agency has also previously provided reports on its repatriation work to the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission. In May, the ADAH is planning to brief representatives from state-recognized tribes regarding the consultation process, though the meeting won’t be a NAGPRA consultation.

“The state-recognized tribes are Indigenous people and Alabamians, so it is appropriate for them to have information on the processes we are following under federal law,” Bowers said.

As the ADAH nears completion of the consultation for ancestral remains in its collection, Bowers noted other challenges lie ahead, such as finding land in Alabama for reburial for tribes from removal states. Another problem facing organizations that are repatriating remains is the issue of security to prevent them from being disturbed again, said UNC-Pembroke’s Strickland Fields. That’s why repatriation ceremonies tend to be very private affairs.

“Are they going to be in a safe location? Is it going to be monitored?” she asked. “... Whatever the circumstances of how these ancestors came out of their graves, this is part of what do we do to return them — how do we protect them in the future?”

Contributing to uneven access to repatriation is a lack of resources to adequately pursue consultation and to house ancestral remains, particularly when the onus of negotiating the transfer of remains — a process that can take years — is often placed on tribes.

Kevin Melvin is the tribal historic preservation officer for the state-recognized Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, a position he’s held since last August. Federally recognized tribes typically designate such officers to provide support for cultural preservation efforts and to work as liaisons between tribes and federal agencies with regard to remains. The position is funded by the federal government. But for the Lumbee, the largest tribe in the state and east of the Mississippi River, that’s not the case.

The Lumbee, located in Southeastern North Carolina, have fought for full federal status for decades. In 1956, the tribe was recognized by Congress but was simultaneously denied the benefits that every other federally recognized tribe receives. Among those benefits would be the funding of Melvin’s position — supported now by the tribe — as well as being fully covered under NAGPRA.

Melvin said the tribe is in the early stages of creating formal policies to guide repatriation and hopes that within a few years they will be able to construct a facility where the cultural items can be stored. He says he understands why NAGPRA incorporates the requirement of proving cultural affiliation.

“Tribes having to designate or go in and prove this is who we are and this is our stuff, yeah, that's kind of a bummer,” he said. “But again, that kind of keeps stuff out of the hands of private collectors and organizations and groups that really don't have anything to do with the tribe, and it makes sure that it goes to the right place.”

State-recognized groups in Alabama echoed those sentiments. Seth Penn, who serves as the governmental affairs liaison for the Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama, said he’s reached out to the Tennessee Valley Authority to be a part of conversations about repatriation. For Penn, it’s important that Native remains are reinterred in their ancestral homelands in Alabama, rather than through federally recognized groups based in other states.

“For me, as a Native person, I know that these spirits can never be at rest until the right ceremonies are done and they are entered into the land where they come from, which is their home,” he said. “Their home is not in a box, their home is not in an institution and … they most definitely don't belong in another state where the tribe has been removed.”

Richardson of the N.C. Commission of Indian Affairs draws parallels between NAGPRA and other federal legislation and programs that leave problematic gaps in protections and services for state-recognized tribes.

“The Indian Child Welfare Act only applies to federally recognized Indians, and NAGPRA only applies to federally recognized Indians,” he said. “But American Indians live all over this country, in every state and county in the United States, every city all over the United States. … So then the question is, what happens to the rest of our Indian people?”

(This story was edited on May 3 to clarify where ADAH is looking for land for reburial.)

Tags

Maydha Devarajan

Maydha Devarajan is the 2023 Julian Bond Fellow at Facing South. She previously worked as a reporter for the Chatham News + Record and as a metro reporting intern at the Raleigh News & Observer. Maydha has also served as a research intern with UNC-Chapel Hill's Southern Oral History Program and the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media.