'No end of trouble': The radical organizing of Durham's Jewish cigarette rollers

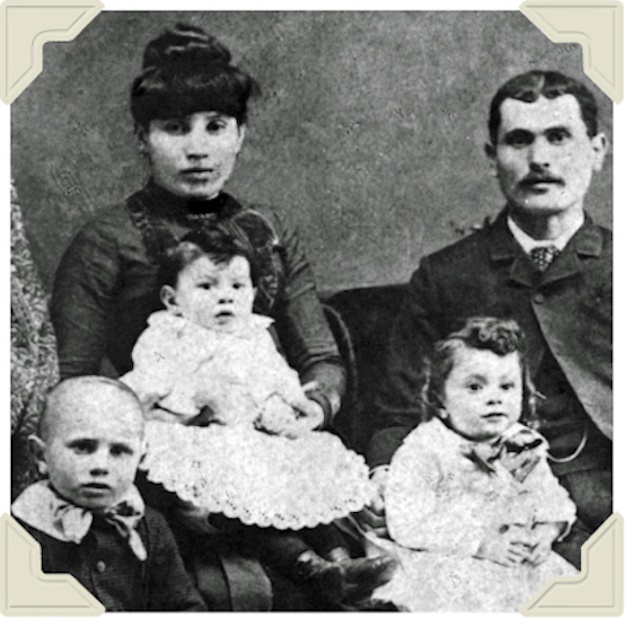

Moses Gladstein and his family. In 1881, James Buchanan "Buck" Duke went to New York City and hired Gladstein to find other striking Jewish immigrant cigarette rollers for his factory in North Carolina. Duke was sure the workers would not be able to organize a union in Durham, but he was proven wrong. (Photo courtesy of Jewish Heritage North Carolina.)

In 1881, tobacco mogul James Buchanan "Buck" Duke and his W. Duke, Sons and Co. of Durham, North Carolina, ventured into new territory for the South: cigarette making.

Cigarettes had first become popular in Europe in the 1830s, and factories making them began opening in New York City in 1864. There, bosses found cheap labor in Jewish immigrants, some of whom had learned to roll cigarettes in European high society. For manufacturing loose pipe tobacco, the Dukes had relied largely on African American laborers from rural communities. But rolling cigarettes required skills no North Carolinians had, Black or white.

So Buck Duke ventured outside of the state to look for suitable workers. He ended up in New York City, where he met Moses Gladstein, a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine — then part of Imperial Russia, along with a large swath of Eastern Europe. Gladstein, who learned to roll cigarettes from Russian nobility, had recently lost his job at New York's Goodwin Tobacco Factory for leading a strike. But that didn't bother Duke, who was confident that his experience overseeing workers — combined with North Carolina's staunchly anti-union labor laws, and workers' isolation and poverty — would prevent his cigarette rollers from organizing.

Duke hired Gladstein and tasked him with organizing a group of fellow strikers to move with him to Durham to work in the new cigarette factory. Duke even paid the workers' train fare. Duke's competitor W.T. Blackwell and Co., manufacturer of Bull Durham Tobacco, responded by hiring its own Jewish rollers, pushing the total number of Jewish immigrant rollers brought to Durham from New York City at the start of U.S. cigarette manufacturing to well over 100.

What ensued is an oft-forgotten chapter of Durham's history: a brief interlude in which leftist Jewish cigarette rollers came from New York, worked, organized, and were fired — and then, in most cases, left. The story has been detailed in a few books, including Leonard Rogoff's "Homelands: Southern Jewish Identity in Durham and Chapel Hill, North Carolina" and Dolores Janiewski's "Sisterhood Denied: Race, Gender, and Class in a New South Community." It was told perhaps most famously in Eli N. Evans' "The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South," discussed in the accompanying sidebar. The account that follows draws on all of these sources, as well as immigration and census records, wills, gravestones, letters, and an unpublished memoir by one of the rollers.

About a decade after Duke's plan to hire striking New York Jews and keep them from organizing ended bitterly, Buck Duke's father, Washington Duke — the "W" in W. Duke, Sons & Co. — assessed the outcome of the scheme in a column he wrote in The News and Observer of Raleigh, then an openly white-supremacist publication: "We never had any trouble in the help except when 125 Polish Jews were hired to come down to Durham to work in the factory. They gave us no end of trouble."

Between Black and white

Rogoff, who's also the president of and research historian for Jewish Heritage North Carolina, called the case of Durham's Jewish cigarette rollers unusual in the context of Southern Jewish labor history.

"In 'Homelands,' one of the things I observed was that the larger the city, the more Jews," he said. "The Jewish immigrant generation were employed in industrial trades, were proletarians, industrial workers. Whereas the promise of a small town was that it offered the opportunity to be an independent tradesman, peddler, storekeeper. So it was very rare to find Jewish industrial workers in the South."

Incorporated in 1869, just four years after Confederate General Joseph Johnston surrendered to Union General William Sherman at a nearby farmstead, Durham had about 2,000 residents by 1880, among them a few German Jewish merchants. When the Eastern European Jews arrived from New York the following year, they lived near Duke's factory on Pine Street, which was nicknamed "Yiddisha Streetal" and characterized by rough shacks, animal pens, and warehouses. Steve Schewel, who served as Durham's mayor from 2017 to 2021, reports that his Jewish immigrant great-grandfather Elias Schewel was a kosher butcher in Lynchburg, Virginia, who visited Durham regularly to supply suitable meat for the rollers.

Rogoff described life for the Jewish newcomers: "They lived down in the Bottoms, really, between white Durham and Black Durham," he said. "They occupied a middle ground. And then eventually, as they left the proletarian trades, became more prosperous, they moved up the hill into the white neighborhoods."

But first, they labored. The Jewish immigrant rollers in Durham's cigarette factories worked six days a week, from early morning until 10 at night. Their needed skill meant they were paid better than native Southern workers: 70 cents per 1,000 cigarettes for premium brands. Based on an expected output of 2,500 cigarettes rolled per day, this meant a weekly wage of $8 to $10, at a time when the average annual pay for a man in Durham was less than $300.

The job was tedious. Here's how Rogoff describes it in "Homelands":

Six rollers worked at a long table behind four-foot partitions. Black workers hauled boxes of tobacco from a nearby log cabin and placed them on the tables. The roller took paper and shredded leaf (the "makin's" or a "monkey"), wet and matted it, and then rolled it on a marble or pasteboard slab (a "kleunky"). The paper was pasted into tubes with a flour and water mix. Some New Yorkers used another technique, forming the paper around a stick and then packing it. Taking four or five tubes in hand, the roller cut them into cigarette lengths with a sharp blade.

By 1883, Duke's rollers were producing 250,000 cigarettes per day, Rogoff reports — which was not enough to meet demand driven by the company's aggressive marketing, including innovations like collectible cards, some with pinup-type photos. So Duke innovated again. On April 30, 1884, the company installed a cigarette rolling and cutting machine invented by James Bonsack of Virginia.

That's when all hell broke loose for Buck Duke.

A pathbreaking union

The outraged Jewish cigarette rollers — who had been kept on by Duke because the new machine designed to replace them broke down so frequently — threatened to destroy it. Bonsack's mechanic, William O'Brien, received anonymous death threats. In the end, though, the rollers decided on a different kind of resistance: They would unionize.

There was little historical precedent for union organizing in Durham's tobacco factories. In 1875, when Black tobacco workers at the Bull Durham factory had collectively advocated for higher wages, they were all fired and replaced. But the Jewish rollers — many of whom had witnessed or even took part in revolutionary movements in Europe — were undeterred. In July 1884, some of the Jewish rollers allied with some of their white coworkers to form Local 27 of the Cigarmaker's Progressive Union (CMPU), which in turn was formed by socialists who quit the Cigar Makers' International Union over its support for mainstream U.S. politicians they considered corrupt. Because the union represented skilled workers, it did not include Black people, who Duke and wider Southern society restricted to unskilled jobs.

William Blumberg of the union journal Progress reported in 1884 that the CMPU local was the first of its kind in North Carolina. The local initially had just 14 members, and seven of its nine officers were Jewish. In just a few months, though, the union grew to over 70 members, the majority reportedly immigrant Jews from New York.

But as the rolling machine became more reliable and its output increased, Duke began phasing out the rollers, reducing quotas and cutting wages by two-thirds. The rollers were incensed, with union secretary Junius Strickland — a native Southerner — even going so far as to encourage his fellow workers to arm themselves.

The company responded by imposing what the workers called "tyrannous shop rules" and levied fines for breaking them that came out of workers' pay; it also increasingly allocated work to white Southerners trained by the Jewish rollers. Rogoff's book cites a roller who reported that the natives "not only remain outside the union but oppose it and try to prevent its progress in every way that they can conceive, also acting very unkindly to all union hands, thinking it a sin to disobey the boss." In CMPU records, Rogoff found accounts in which Jewish cigarette rollers claimed to have been driven away by Duke through deliberate impoverishment.

After the national CMPU shifted from a general tobacco workers' union to one that represented only cigar makers, the Durham chapter collapsed. In partnership with members of the whites-only National Farmers Alliance and Industrial Union, some former CMPU members organized a local assembly of the Knights of Labor, the 19th century labor federation that broke ground by organizing across racial and gender lines and by welcoming both skilled and unskilled laborers.

Though the Knights did not pursue an official strike in Durham's tobacco factories, they led work stoppages. But the organization faded as the last of the Jewish cigarette rollers were phased out of their jobs in Duke's factory in 1888 — and as white supremacists, then ascendant politically, attacked the union for welcoming both Black and white people.

In "Sisterhood Denied," Janiewski observes that the Jewish cigarette rollers' organizing efforts drew attention to and prompted public debate about practices within Duke's factory, such as extreme shop rules, child labor, and the physical whipping of child workers. That mattered, because by 1890 over 13% of Duke's tobacco workers were children. Though Congress outlawed child labor with the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, the law excluded agricultural labor. Consequently, the tobacco farming industry still has a problem with the use of child labor today, much of it involving immigrants.

Life after rolling

When Duke pushed them out of their jobs in Durham, most of the Jewish cigarette rollers headed back north, as Rogoff details in "Homelands." But some stayed in Durham or moved to other communities in the South. Many became merchants. Those who remained in Durham helped organize the city's first formal Jewish congregation, Durham Hebrew Congregation, in the late 1880s in a rented hall on Main Street. After World War I, the congregation built a large cathedral-style synagogue downtown, Beth El Synagogue, which started out as Orthodox but later hired a Conservative rabbi after the congregation grew more liberal.

In the 1980s, the president of the Beth El Synagogue Sisterhood was Lynne Grossman — the great-niece of the same Moses Gladstein who Buck Duke hired to launch his cigarette business. She currently serves as the executive assistant at Jewish Heritage North Carolina. Her grandfather, Louis Gladstein, was Moses' brother. But Louis died in 1942, three years before Lynne was born, and she says she knew nothing about Durham's Jewish cigarette rollers until Rogoff published "Homelands."

Grossman reports that her great-uncle used the $1,000 buyout Duke paid him to start a dry goods store with Louis in Durham. The store operated for almost a century before closing in the early 1970s, though Moses Gladstein and his family moved to Baltimore in the 1920s. When she was growing up, Grossman said, many stores in Durham were owned by Jews. However, she was usually the only Jewish child in her classes at school.

"Most of my friends were gentiles," she said, "but I went to Hebrew school, I went to Sunday school, I was bat mitzvahed."

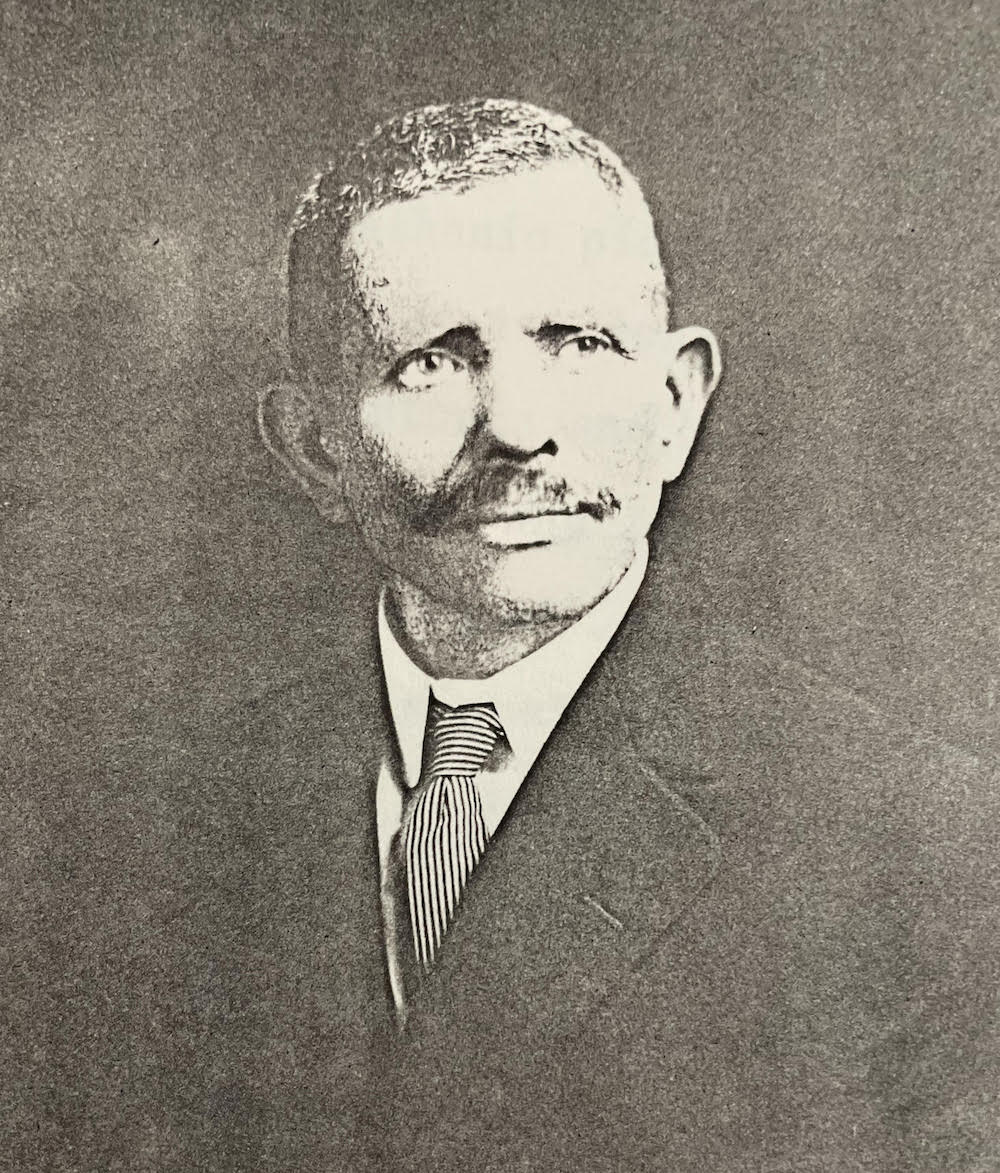

Among Durham's Jewish cigarette rollers who moved to other Southern cities was Bernhard Goldgar, who had Polish roots. In an unpublished memoir, he described his conversion to socialism: "Was not I myself one of the millions who are entangled in that great spiderweb called social system, struggling no less than so many flies to get free, yet getting more deeply entangled, the more we struggle until death relieves us?" Goldgar stayed in Durham until the early 1890s, when he moved to Macon, Georgia. There, he served as president of an Orthodox synagogue, Congregation Sherah Israel, and faced criticism for his leftist politics and for not keeping kosher.

Shari Rabin, associate professor of Jewish Studies and Religion at Oberlin College in Ohio, said a travel log by a Yiddish socialist writer and a commemorative booklet by Der Arbeter Ring (The Workmen's Circle), a Jewish socialist Yiddishist group, both refer to a radical leftist president of an Orthodox Jewish synagogue in Macon. Rabin believes these texts were referring to Bernhard Goldgar.

"He's interesting to me as this person who has these radical leftist ideas and moves south and adapts and becomes a businessman and becomes president of the Orthodox synagogue," she said, "which might seem incongruous, but still I think harbors this kind of radical sensibility."

Rabin also found records indicating that Goldgar served on a local committee for the Industrial Removal Office (IRO), a nongovernmental organization that in the early 20th century helped resettle in the United States newly arrived Jewish immigrants fleeing European antisemitism. A traveling representative from the national IRO described Goldgar as "well-respected" and "idiosyncratic."

"That shows that he had become a leader in the Macon community," said Rabin, "and was committed to developing that community, and also to helping other Eastern European Jewish immigrants."

Nevertheless, the story of the Durham cigarette rollers has been largely forgotten — even within their own families. Reached at his home in Salt Lake City, David Goldgar, Bernhard's great-grandson, said he was not aware of his ancestor's political ideology, nor his time as a cigarette roller in Durham. Deborah Barber, David's sister and Bernhard's great-granddaughter who lives in Seattle, noted that she was just 10 when her grandfather, Bernhard's son Benjamin, died.

"He smoked a pipe that smelled of cherry tobacco, and he could take his dentures out," she said, recalling her few memories of her grandfather. "So I didn't really know."

Tags

Sofia Lesnewski

Sofia Lesnewski is a senior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, studying English and comparative literature, Spanish, and social and economic justice. She previously covered higher education, diversity, and representation at The Daily Tar Heel, and she currently serves as editor of The Journal of Women and Criminal Justice, a national publication for justice-involved women and advocates.