Southern communities launch mental health response teams without police

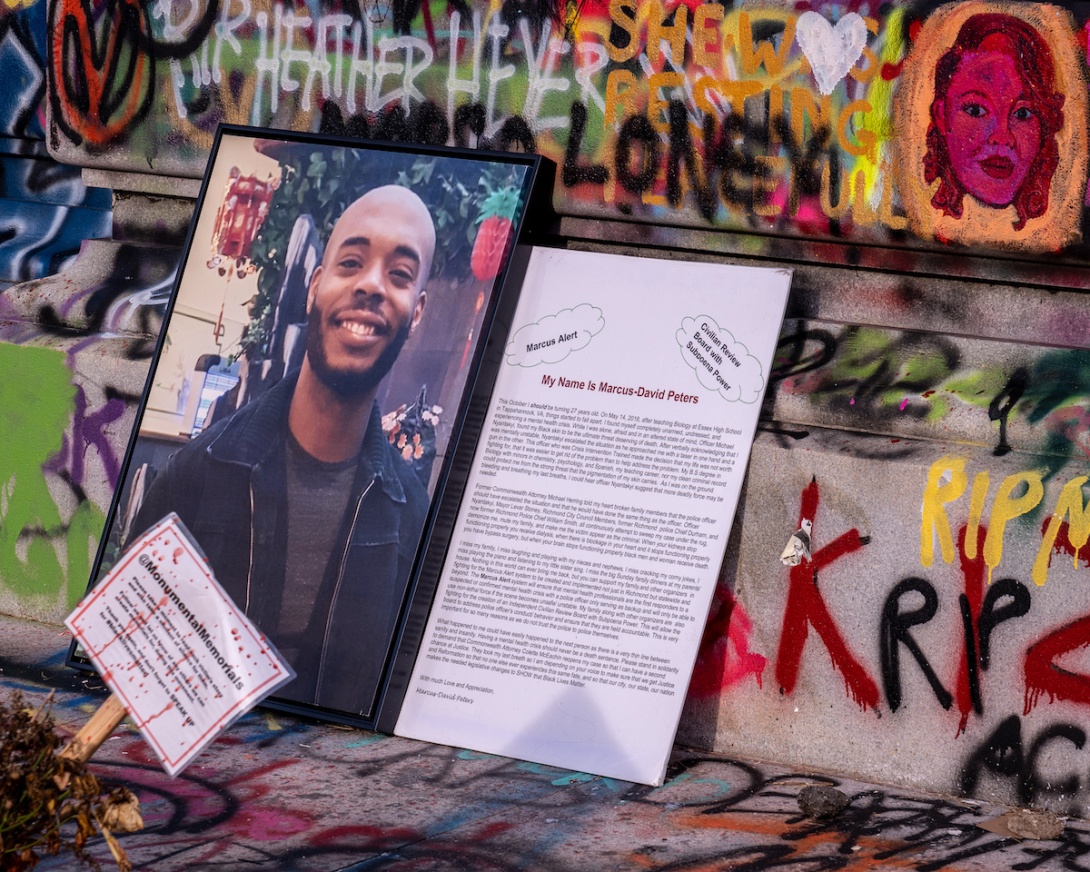

Marcus Alert, Virginia's mental health crisis response system, was named after Marcus-David Peters, a 24-year-old Black man who was killed by a Richmond police officer in May 2018. During the 2020 protests against police brutality, demonstrators renamed a Robert E. Lee Monument in the state's capital "Marcus-David Peters Circle." (Photo by Mobilus in Mobili via Flickr.)

(This story was corrected on Aug. 12 to note the hours that CALL services are available in St. Petersburg, and to clarify the percentage of suicide calls it's diverting.)

Of the 1,140 people killed by police officers last year across the United States, 101 were experiencing a mental health crisis, according to data collected by Mapping Police Violence.

In response to the police reform movement's demands to address the problem, a growing number of communities are launching unarmed mental health crisis response teams, which either involve no police or involve them only as a last resort.

While there's no firm count of how many civilian-led crisis response teams exist in the U.S., Eugene, Oregon, is home to one of the first, according to the Vera Institute for Justice, a national group that works to end overcriminalization. Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets, or CAHOOTS, began in 1989 and involves a two-person, unarmed team responding to mental health crises.

"Over three decades, CAHOOTS staff has never reported a serious injury," Daniela Gilbert, Vera's Redefining Public Safety director, told Facing South. "The assumption that we need police to respond to these calls isn't borne out in the programs that we've seen where police are not involved."

Similar mental health crisis response teams exist in Denver and Olympia, Washington. In the two years since nationwide protests against police brutality, some of these programs have spread to communities in the South.

Facing South spoke with officials involved with new mental health crisis response teams in St. Petersburg, Florida; Durham, North Carolina; and Virginia to learn more about the efforts.

CALL in St. Petersburg

The city council in St. Petersburg, Florida, unanimously approved the Community Assistance and Life Liaison (CALL) program in January 2021. It launched the following month with $850,000 in city funding; the budget has since increased to $1.2 million. The program is staffed by licensed mental health professionals at Gulf Coast Jewish Family and Community Services, a local nonprofit. The city first annouced the concept in July 2020 during nationwide protests against police brutality.

If someone in the city is experiencing a mental health crisis, or they want to help someone who is, they can call the police non-emergency line or 911. They can get help from a licensed clinical social worker over the phone, or two mental health professionals, called "navigators," will be dispatched to help them in person. The navigators are available from 8 a.m. to midnight8 p.m daily while the call line operates 24/7.

Since the CALL program's inception, the CALL team has decreased the number of suicides in St. Petersburg decreased calls being handled by police by 17%, and nearly 80% of suicide calls have been diverted to the team's mental health professionals, according to Megan McGee, the special projects manager at the St. Petersburg Police Department. She helped develop CALL and serves as a liaison between the program, the emergency communications department, and the police.

"Our goal was to divert these calls from law enforcement as much as possible," she said.

Durham has HEART

Durham, North Carolina, launched the Holistic Empathetic Assistance Response Teams, or HEART, program, in June. HEART is separate from the city's police-led Crisis Intervention Team, which educates police officers about mental health and de-escalation tactics.

The HEART team is housed within Durham's Community Safety Department, which provides alternatives to traditional policing. Besides dispatching unarmed mental health professionals to help those in crisis and following up with them, the HEART program is also adding mental health clinicians to the 911 call center and creating a team of mental health professionals able to co-respond with law enforcement on a case-by-case basis.

Durham City Council member Jillian Johnson, an advocate for the program, said the city had discussed unarmed mental health responders since at least as far back as 2019.

"It's really important for people who have mental health issues to access help when they need it. Unfortunately, the majority of help that's available to you is the police," Johnson said. "That's not what people who are having a mental health crisis need. It also exposes them to really severe potential collateral consequences — everything from arrest and injury to death."

Marcus Alert in Virginia

Virginia's statewide mental health crisis response system is called Marcus Alert after Marcus-David Peters, a 24-year-old Black biology teacher who was having a mental health crisis when he was shot and killed by a Richmond police officer in May 2018. Peters was unarmed, but the officer who fatally shot him was not charged for the killing after the Commonwealth's Attorney ruled that the shooting was "justifiable homicide."

The state legislation to put the program's framework in place was signed by Gov. Ralph Northam (D) in late 2020, and it began operating in Richmond last December. Marcus Alert responds to mental and behavioral health crises by connecting 911 dispatch with regional crisis call centers. Mental health professionals there either help people in mental distress over the phone or in person with an unarmed team of licensed clinicians. As with the Durham program, law enforcement is dispatched to the scene only as a last resort.

The program is also currently operating in Madison, Fauquier, Prince William, and Washington counties, and the communities of Warrenton, Culpeper City, Bristol, Abingdon, Damascus, Glade Spring, and Virginia Beach. Most localities are required to adopt the program by 2026. A law passed in the General Assembly this year allows areas with fewer than 40,000 people to opt out of the alert system, but people in crisis can still call 911 or 988 — the new number for the national suicide prevention hotline — and receive mental health assistance, according to Alexandria Robinson, the Marcus Alert program and training coordinator at Virginia's Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services.

The planning for Marcus Alert involved state leaders in mental health, racial justice, disability advocacy, and substance abuse awareness. One of the advocates involved, Sabrina Burress, is the executive director of The Arrow Project, a mental health organization based in Staunton, Virginia. Burress emphasized the importance of having Black-led organizations involved in shaping the program.

"We all have this hope that members of the Black community will feel more comfortable saying, 'Hey I need some help,' or 'Hey, my brother needs some help,' or 'Hey, my mom's not doing OK,'" Burress said. "We can connect that person to services, before them having to have an interaction that frankly, could be the end of their life."

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.