Beyond white guys in hardhats: Kim Kelly on labor's hidden history of diversity

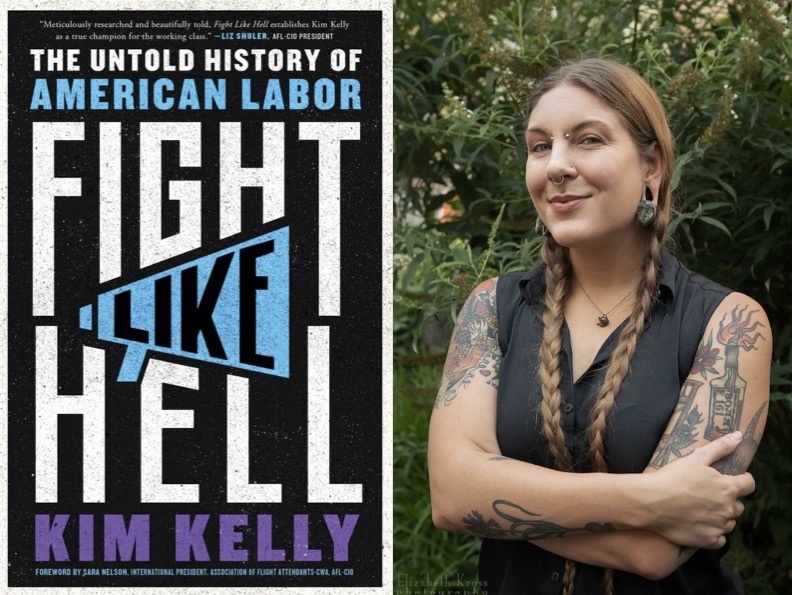

Kim Kelly is a labor reporter and the author of "Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor." (Photo of Kelly by Elizabeth Kreitschman courtesy of Simon & Schuster.)

Workers at Warrior Met Coal in Alabama recently marked more than 400 days on strike — the longest in the state's history. As the Alabama miners continue to hold the line, Starbucks employees recently won union elections in that state as well as Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas.

These brave workers — Black and white and Latino and Asian; women, men, and nonbinary people — are carrying on a centuries-long history of labor organizing in the South. But many of the oft-told stories of successful organizing efforts in the region and the nation at large have either been relegated to obscure academic texts or center the struggles of white men.

In "Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor," labor reporter Kim Kelly rectifies this marginalization with accounts of how Black workers wielded the power of collectivized labor to organize in the Reconstruction-era South and beyond. Kelly is a freelance reporter based in Philadelphia who has written for the Washington Post, The Baffler, and The New Republic, and pens a labor column for Teen Vogue.

As Kelly recounts, after the Civil War freed Black people sought opportunities to work and own property alongside their white counterparts. But Southern state legislatures, seeking to extend the oppression of Black people, passed a series of laws known as "Black Codes" that among other things limited the rights of Black workers. In South Carolina, for example, Black workers were forced to enter into contracts with white landowners that labeled them as "servants" and required them to work and reside on the property of their "masters." These labor contracts criminalized communication among and movement of workers. Violations often meant forfeiture of wages and sometimes carried a jail sentence.

This system of slavery by another name gave way to a practice known as convict leasing, where people imprisoned under laws specifically designed to target Black people were then leased to local industrialists or farmers and forced to work under harsh conditions without pay. Widely practiced in Southern Appalachia, convict leasing generated millions of dollars for the U.S. economy during the 19th century through activities including coal and salt mining. It was only through the organizing of Black mine workers that the practice received national attention and was eventually abolished, first in Tennessee, then Georgia. Alabama abolished it much later.

Following the Civil War, many Black women took up domestic labor, including laundry work. In 1866 a group of Black laundry workers in the Mississippi capital launched a massive strike after city officials dismissed their appeal for fair wages. At the time, their plight was overshadowed by that of white millworkers in the North, though they drew support from the region's abolitionists. The workers eventually founded Mississippi's first trade union, the Washerwomen of Jackson. Soon after, Black-led labor organizing spread throughout the South, from the formation of the Colored National Labor Union in 1869 to the Great Strike of 1877, which started in West Virginia and eventually spread to other states including Mississippi, where many strike leaders were Black railroad and dock workers married to members of Washerwomen of Jackson.

One year after the Jackson strike, Congress passed the Peonage Abolition Act, outlawing debt slavery like that experienced by so many Black workers after the Civil War. However, Black sharecroppers in Arkansas still found themselves unfairly indebted to white land owners. These sharecroppers returned from fighting in World War I to form the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) with the aim of negotiating fairer settlements with landlords. But the union's attempt to organize resulted in the kidnapping of the union president's son, who was assaulted, labeled a "labor agitator," and jailed.

Over the next two days, a mob of white civilians, police, and military servicemen unleashed violence on union members and the wider community of Elaine, culminating in the deaths of at least 100 Black people and the jailing of an additional 285. The event became known as the Elaine Massacre, which is still commemorated today. Though the union dissolved, a dozen Black members known as the Elaine 12 were convicted for their alleged roles in the massacre — and later exonerated after a 1923 landmark Supreme Court case, Moore v. Dempsey, forever changed the way courts interpret due process. Not long after, A. Philip Randolph began organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first Black-led union to successfully negotiate a contract with a major corporation and receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor. Its motto was "Fight or Be Slaves."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Who are some of the people who have been left out of the conversation about labor in the United States?

The book focuses specifically on women, Black, Indigenous, Latino, Asian Pacific Islander workers, disabled workers, queer and trans workers, immigrant workers, workers whose labor has been criminalized like sex workers, or people in prison. Those are all people and groups whose stories have been documented and preserved by academics and historians and contemporary journalists at the time, but those histories aren't necessarily made available or accessible to most of us. There's a lot of really incredible academic writing and research that's kind of locked away in these archives or only available in academic presses, and a lot of folks that are are interested in or would be interested in this history don't have anywhere where to look. I wanted this book to weave together different stories and characters and moments to show not only has labor history always been intersectional, inclusive, and diverse, but it's really those workers who typically have been the most vulnerable, the most marginalized, who fought the hardest.

How has this helped to shape or maybe warp the image of America's working class?

There is this enduring avatar of what a working-class person looks like, or what a union worker looks like. And it invariably ends up being someone like my dad, like a white guy in a hard hat with dirt on his hands, who has dodgy political opinions and is not interested in the radical or even progressive aspects of labor history. That's not to say that those folks aren't a part of the movement. They've always been here, they raised me, they're important too. But that's not the whole story. Even just in stark, modern terms, the most common union worker you'll come across is a Black woman who works in health care. The typical union worker right now is not a guy like my dad. Given how union density has fallen and how work itself has changed, that old stereotype just isn't going to cut it anymore. And I think it's really important to show that every type of person has been part of this movement and done incredible things. And there's no reason why we can't do it again.

I think it's really important to show that every type of person has been part of this movement and done incredible things. And there's no reason why we can't do it again.

A few chapters of the book focus on Black domestic workers — I'm thinking specifically of the Washerwomen of Jackson, Mississippi. How does their legacy endure today?

Domestic workers face this conundrum where the actual labor they perform, whether it's caring for children or elders, whether it's cleaning, whether it's just maintaining the home — there's been this pervasive image throughout history that that's not even work. That's just what certain people are supposed to do. Why would we pay you for that? Whether, you know, it's been discussed in context of the Wages for Housework campaign, or just the way that domestic workers were left out of major labor legislation, and still are. There are so many people in this country, so many workers, who not only are fighting for decent wages or protection on the job — they are fighting just to be recognized as workers. This is something that we've seen throughout decades and centuries and are still seeing now.

Several of the organized movements in the book began down South, then made their way up North, which is sort of the opposite of how stories about labor are often presented. How does a movement travel from, say, South Carolina to Pennsylvania?

Even before technology was part of the equation, it came down to networks, right? Building networks of solidarity, staying connected with activists across state lines and building a real community of workers and organizers. One of my favorite examples of Southern workers innovating, and coming up with new ways to use new technologies to their advantage, was during the Great Textile Workers Strike in 1934. There was this massive textile workers strike going on, and at one point workers formed these things they called "flying squadrons." They use this new shiny technology as a way to spread the news of the strike and connect with workers and get them to join in. These flying squadrons were just made up of automobiles. That was a new thing back then — that was before we had Twitter, before we had Discord. That revolutionized the way that people were able to connect to the news of strikes and labor unrest.

How has the history of slavery, forced labor, and Jim Crow in the South shaped the labor movement?

There's this tendency to sort of silo off specific historical moments or movements for justice as their own thing, whether it's like, you know, the disability rights movement, or the civil rights movement. Those have always intersected with the labor movement and the history of slavery in the South — that was labor, it was forced labor. It's something that you can trace direct lines from, from slavery to convict leasing to incarcerated workers in prisons across the country. Everything's connected and builds on something that people before have struggled against. Every fight we're dealing with right now, someone was already doing that 100, 200, 400 years ago.

The book notes that Black women were mine workers as early as 1821, centuries before the white woman who is actually credited for being the first woman to work in the mines. How does writing enslaved people out of the labor movement in this way make building power more difficult?

I don't think you can really understand the labor movement as it stands now, or how it got here, or the mistakes it's made, or the successes that it has notched, without understanding the impact of slavery and the impact of forced labor. So many firsts in this country didn't ask to be first, and a lot of their names are lost to history. When I was researching the chapter on mining, I couldn't find any names [of enslaved people] or any of their voices. It kind of broke my heart because they're pioneers. They're labor heroes, too.

In the book you talk about the practice of convict leasing and how it was widely practiced in Appalachian states after, and in Alabama's case before, the Civil War. How has this practice shaped current systems of incarceration, and what role has abolition played in the labor movement?

We're a few decades removed from that particular historical moment. But there are still people in prisons who are seeing their labor sold to companies and seeing those companies and the U.S. government profit enormously off of their labor. They don't have a choice, they're not able to push back against their boss, they can't clock out. They have no rights as workers. In North Carolina — I researched the prisoners' labor union movement there in the '70s — there's one specific Supreme Court decision that jumped out at me as a catalyst that kneecapped the nascent prisoner labor union movement when it was really just picking up steam.

In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled in the Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners Labor Union case that incarcerated workers don't have a right to join the union or to organize a union. Even though they're workers and even though they're enduring those material conditions, they are not allowed. I think we've really seen the impacts of that four decades later. But of course, people in prison have continued to organize; incarcerated workers have continued to strike and resist and rebel. It's interesting to think about how the labor movement intersects with abolitionist movements because I think and hope a lot of us within the two movements are committed to actually getting people free and to understanding and emphasizing that intersection between incarcerated workers and labor. Again, it's all connected.

And one thing that complicates that in an interesting and really enduringly frustrating way is the fact that cops, police, they are ostensibly part of the movement, right? They have their "unions," hard air quotes around them, but still, they have unions. Their collective bargaining agreements have arguably a hell of a lot more power than a lot of other unions that represent actual workers in this country. Something we saw pop up gave me a lot of hope, at least momentarily. I think it was like 2020 that we saw this little movement, the no cop unions movement. I was involved in that, trying to call on the AFL-CIO to disaffiliate a police union. Union members and leaders were pushing pretty publicly, saying hey, these are the people who are murdering and caging and oppressing our fellow union members, our fellow workers — they should not be part of this federation. It was interesting seeing how much pushback it got.

The end of the book brings us to the present moment of the ongoing Warrior Met Coal strike in Alabama. From your view, how does this strike reflect the efforts to organize labor in the South that you researched for the book?

One thing that was really fun about putting this book together, and especially the way that I structured the chapters, is that I wanted to make it very, very clear how much current struggles were connected to things that happened in the past. Every chapter starts with something a little further back in the mists of time, whether it's, you know, 19th century, 20th century. And then I wanted to show something very current at the end. So much progress has happened in between, but so many people have been left out. Even though that's not the rosiest view, it's true. And I think it's important to show that, whether you're a coal miner in the 1800s or 2021 going to war against a coal boss who is trying to prevent you from organizing, everything old is new again. Putting a more inspiring positive spin on it, so many of the ways that workers won in the past, we're seeing that happen again.

I love it and I didn't put it in the book because it happened after I turned it in of course, but after the [Amazon] labor union won their their union recognition battle in Staten Island, I was reading about it from other really great journalists who have covered it the whole time, like Luis Feliz Leon, Lauren Gurley, Maximillian Alvarez. Organizers Chris Smalls, Derek Palmer, Angelica Maldonado — the tactics they used, whether it was ensuring that people spoke the workers' languages, making sure people felt heard, having barbecues, having jollof rice, showing that they appreciated the culture of the people and saw them as humans, not just robots the way that Amazon did, that took me right back to 1946, the Great Sugar Strike in Hawaii. In order to organize workers, get them ready to strike, and make sure that the white sugar plantation bosses couldn't break them the way they had before by dividing different types of workers, their union at the time, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, pulled together different groups of workers and they had translators, they had meetings where everybody was conversing, they shared food, they built strike kitchens. There was so much of that interpersonal solidarity building. And they won. So many of the tactics that today's organizers are using, even if they don't necessarily know it, are echoing what folks in the past have done to win against their version of Jeff Bezos.

Tags

Makaelah Walters

Makaelah is the 2022 Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a reporter for the Watauga Democrat and interned as an editorial assistant for the nonprofit advocacy group Appalachian Voices.