Appointee will give DeSantis a high court majority as it weighs Florida abortion ban

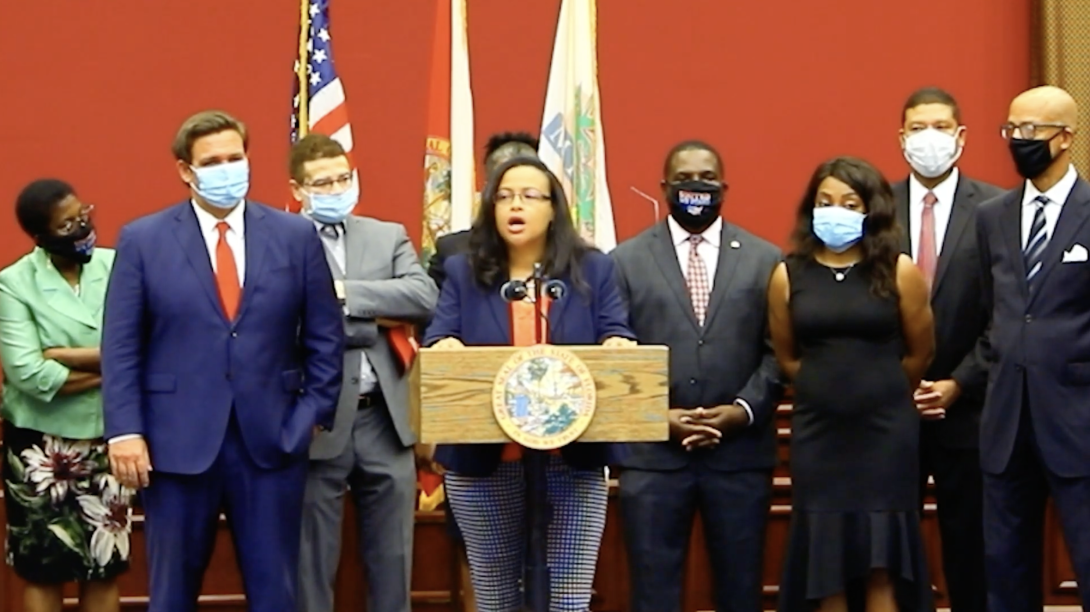

Judge Renatha Francis spoke at a 2020 press conference where Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (at left in red tie) announced that he was appointing her to the Florida Supreme Court. That appointment was blocked, but DeSantis could soon appoint the conservative jurist to an upcoming vacancy. (Still from video on the governor's YouTube channel.)

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a possible Republican presidential candidate in 2024, will soon make another appointment to his state's highest court because Justice Alan Lawson is retiring in August. This will give DeSantis a majority on the seven-member Florida Supreme Court, whose members were all appointed by Republican governors, just as the court is about to consider a lawsuit that claims the new state law banning abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy is unconstitutional.

DeSantis is rumored to be considering Palm Beach County Circuit Court Judge Renatha Francis, who would be the only Black justice and the second woman on the current high court. Like the other three current DeSantis appointees, she's a conservative jurist. For example, a recent article in Insurance Journal suggested that Francis would be a "friendly umpire" for insurance companies. The governor tried to appoint Francis to the court in 2020, but her would-be colleagues ruled that she didn't qualify because she hadn't practiced law for 10 years, as the Florida Constitution requires.

State lawmakers have called on the governor to bring greater racial diversity to the Florida Supreme Court, which currently has no Black justices even though Black people account for over 13% of Florida's population. But when Francis was first nominated in 2020, some lawmakers opposed her as less qualified than other Black applicants, and Rep. Geraldine Thompson, a Black Democrat, was the plaintiff in a lawsuit asking the high court to block the appointment. Francis was the only Black person on the list of potential appointees to both the 2020 vacancy and the current seat. The list is drawn up by the state judicial nominating commission, whose nine members are appointed by the governor to screen potential appointees and submit a list of three to six names for the governor to choose from.

Francis and the other potential appointees chosen by the commission are all affiliated with the right-wing Federalist Society, whose members occupy seats on high courts across the country and make up a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2020, DeSantis' lawyer told the group that its conservative ideology was the "litmus test" for appointees. In fact, the governor's first three Supreme Court picks were personally interviewed by Leonard Leo, the Federalist Society's former leader. Florida governors have had the power to appoint a majority of the judicial nominating commission since 2001, and DeSantis has filled it with Federalist Society members.

The commission recommended five other potential nominees. The list includes Denise Harle, a white woman who serves as senior counsel with Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative Christian legal advocacy group that has worked to block protections for LGBTQ people and abortion access. Harle also served as a lawyer for the state of Florida and defended an anti-abortion law before the state Supreme Court in 2017. Her page on the Federalist Society website touts her work defending anti-abortion laws.

Overturning abortion precedents

Like the U.S. Supreme Court, Florida's high court could soon overturn crucial precedents protecting abortion rights in a state that has some of the strongest abortion protections in the South. In 1980, seven years after the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion, voters amended the Florida Constitution to protect "the right to be let alone and free from governmental intrusion into the person's private life." The amendment was proposed by a feminist law professor as a backstop in case the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe. The proposal, which had bipartisan support in the legislature, passed with the support of 60% of voters.

The Florida Supreme Court cited the 1980 amendment in 1989 and 2003 rulings striking down laws that limited access to abortion for minors, although one of those decisions was eventually overturned. And in 2017, the court blocked a law that required a 24-hour delay and biased "counseling" for people getting an abortion, citing "the Florida Constitution's express right of privacy." The privacy provision is clearly popular with the people of Florida: When Republican lawmakers put an amendment on the ballot in 2012 that would have effectively excluded abortion from the 1980 amendment's protections, voters rejected it by a 55-45 margin.

The Florida Supreme Court has already upended precedents in other areas of the law in recent years, including appeals from death row. The justices said they'll now overrule any precedent that "clearly conflicts with the law." Justice Jorge LaBarga, a former assistant public defender who served as chief justice from 2014 to 2018, has often been the only dissenter in these cases.

Health care providers and abortion rights advocates recently sued Florida in state court over the new state law banning abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy; a synagogue also filed a lawsuit challenging the ban as violating its members' religious freedom. The ban appears to violate the Florida Constitution as previously interpreted by the state's high court, but the justices could overturn those precedents and reinterpret the right to privacy.

If the court strikes down abortion rights in Florida, that would leave one fewer state where access to abortion care would be protected under the state constitution if the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe, as it's expected to do soon. A recent report from the Center for Reproductive Rights discussed 11 states where supreme courts have recognized that their state constitutions protect abortion rights more strongly than the U.S. Constitution or have struck down restrictions that were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court; Florida was the only Southern state on the list. Meanwhile, citizens in a number of states including Kentucky will vote on amendments this year specifying that abortion rights are not protected under their state constitutions.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.