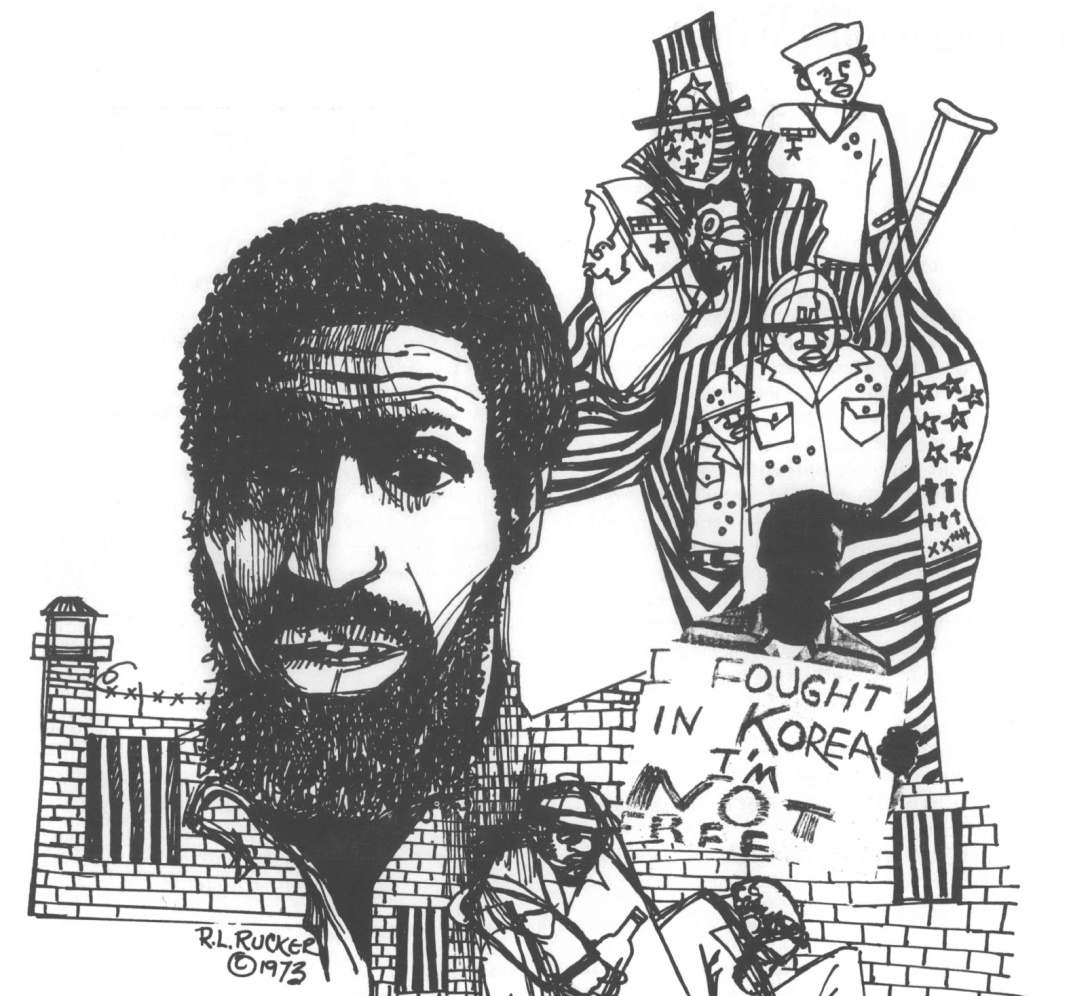

From the Archives: War resister Walter Collins on racism in the U.S. military

(Illustration by R.L. Rucker for Southern Exposure.)

Published in 1973, the first issue of Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South, was devoted to the intersection between war, civil rights, and the South's growing military economy. In the introduction to that issue, which came as U.S. troops were leaving Vietnam following the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, editors wrote that "militarism emerges … as the modus operandi of an expansionism which now threatens to turn our collective existence into a global Wasteland."

The issue included an unbylined interview with Walter Collins, a longtime Black Freedom Movement activist who was incarcerated in 1970 for refusing the draft. Collins was involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as well as the Black nationalist group the Republic of New Afrika. His interview touches on questions of colonialism and anti-Black repression in the United States, and is an indictment of the racist aspects of the military. He also speaks to the whiteness of the period's insurgent antiwar movement as well as the difficulties facing Black veterans when they returned home from the war.

Three years after Collins was incarcerated, the U.S. ended the draft — but disparities remain in who serves. Black men are still significantly overrepresented in the military, while the South provides a disproportionate number of recruits. Meanwhile, the region's economy remains mired in defense contracts and subsidies for military contractors.

Collins died in 1995. Segments of a lengthier oral history with him, conducted by Kim Lacy Rogers, are available online via the Tulane University Library.

On the Military: Interview with Walter Collins

Walter Collins was incarcerated in November 1970 for refusing induction into the Armed Services. His conviction followed a long track record in the Movement. An early participant in "sit-ins" and voter registration campaigns, he began organizing opposition to the Vietnam War and the draft in the summer of 1966 in the black community of New Orleans. He has worked on staff with the National Association of Black Students (NABS), CCCO, and SCEF and was the founder of the National Black Draft Counselors (NBDC).

His conviction was a direct attempt to thwart his political activities and those of his mother, Mrs. Virginia Collins, who has been active in organizing and politicizing workers in Louisiana and Mississippi. It was only after Collins publicized the facts that 85% of the draftees in New Orleans came from two predominantly black wards and that 90% of those from that city killed in the war were black, and after his mother refused to testify before the Louisiana HUAC, that both he and his two brothers (one of whom had a congenital heart condition) lost their student deferments.

His seemingly bizarre case — which drew national attention with the help of SCEF — is only another example of the special oppression of black resisters in the tradition of the SNCC resisters of the Sixties — Donald P. Stone, Mike Simmons, Fred Brooks, Cleve Sellers, Bob Moore, Larry Fox, et al. — and of their countless, lesser known predecessors and successors. Bro. Collins was given the wrong information when he tried to apply for C.O. status. He was issued six different induction dates. Twice, when he reported for induction and passed out anti-war literature, he was sent home. Finally, he was indicted on six counts of failure to report and submit to induction (although he reported each time he knew of an order). He was subsequently convicted on five counts, sentenced to five years on each count, to be served concurrently, and fined $2000. His abrupt and gestapo-like arrest came just 11 days after the Supreme Court had refused to hear an appeal of his sentence, even though his lawyers had 25 days to file his petition for reconsideration.

The repression of Walter Collins has only served to sharpen his already keen analysis and active commitment to the liberation of black people and the struggle against U.S. capitalism/imperialism.

The peculiarities and ironies of racism are revealed in the context of the military. On the one hand, blacks and other minority people are the prime subjects of economic impressment into the armed forces. This policy emerged full-fledged with LBJ's Project 100,000, a part of his anti-poverty program, when entrance standards of the Service were lowered in an effort to attract blacks, to get us off the streets, to let us fight the war in Asia and (if we survived) to teach us a skill. On the other hand, however, the recent wave of administrative discharges (52,000 in 1970 and 71 of "undesirables" alone, no figures being available for the even more common "general discharges") is an effort to whisk these same folk right out of the Service quietly (and often with no benefits). At the same time vigorous recruitment policies are being waged in the minority communities, especially since the spectre of the volunteer army, while incarceration continues to be laid on the overwhelming bulk of black war resisters. (The same was true during WWII when 95% of black war objectors were imprisoned as compared to 45% of white objectors.) Thus, racism is so entrenched in this society that it prevents the administration from being able to cope with black people justly enough even to get them to fight its wars. The consciousness of black troops gained from the battlefield is only perfunctory to that produced by the contradictions within the military itself.

The following interview was conducted in mid-January, two months after Collins' parole from federal prison. Unfortunately, it had to be edited because of our space limitations.

Southern Exposure: How did you view the war and the draft when you began organizing around these issues in the black community?

Walter Collins: My perspective was that the war, first of all, was not an aberration as so many people in those early years thought. It was a larger extension of a system that first of all needed people to exploit in order to function. Secondly, the area that it chose to battle in was an area very key to the exploitation of the continent of Asia.

In another sense, I think the antiwar movement begins to reflect the racism of the country. When the sons and daughters of the wealthier class in America began to talk about the draft more or less as an inconvenience to them and started hooking up with the draft, all the government did with that antidraft, antiwar movement was move it into the poor communities of America, particularly in the black community. The thing that finally woke me up was that I suddenly looked around me in 1965 and discovered not one person who had gone to high school and junior high school with me was around. If they had not been killed in Vietnam, they were on their way, with the few exceptions who had gone into the drug thing and were in prison. And that was sort of a shocking thing. I'm saying there was no real antidraft movement. All they did was move the draft from the white community into the black-American, Chicano community, wherever there was not enough of a political clout to begin to raise those issues.

My position is that the draft is genocide in the black community because it very clearly takes the very best, the most skilled, the most articulate, the most useful black men. It is not accidental. The people whom the Army instructors might teach some skills to they don't want. It's the people who clearly might be of use in terms of liberation struggles of black people who they drafted.

S.E.: In your own case, you emphasized the racism involved in the manner in which you were drafted and prosecuted, is that correct?

W.C.: Right. We proved two things about my draft board. I forced them to give me their records for the last 25 years. That area has always been heavily black, at least since the mid-50's, predominantly black. There were never any blacks on the draft board. And what was shown during the Vietnam buildup, from '64 clear on up to '70 (the period we have figures for) was that most of the whites of draft age, who were classified by that board, were either in the National Guard or had deferments. I showed in my case that there were eight people who were 1-A, who were older and should have been drafted before me, who were not. No one ever gave any explanation of that. We also showed that none of the draft board members lived in the area. The chairman and another board member lived in another parish-a clear violation of the law. The government argued that it did not matter if the draft board was not made up according to law, because it was acting as a legally constituted board and should be treated as such. And I went to jail on the basis of that argument.

It was during this period of fighting that I got involved heavily in the antiwar movement there in the city and across the nation, in student issues and in a lot of workers' struggles, particularly in Mississippi in the Laurel area. In fact, I finally went to trial on July 9, 1969, just after the municipal election in Laurel where, though we lost, we were able to fuse the political unity of black and white workers and run a slate of candidates in opposition to the Masonite Co.-the biggest employer in the area.

The push for my indictment and ultimate conviction did not initially come from the federal government. It came from the state of Mississippi and from the state of Louisiana and, of course, in response to my mother's activities also.

The only people at my trial were the FBI, and the intelligence divisions of Mississippi and Louisiana. The guy who prosecuted me was not from the federal government. He was the Chief Legal Counsel of the Selective Service for the State of Louisiana. In my file on that whole period from '66 until '69, there was a series of letters backwards and forwards between my draft board and the governor and the Louisiana House UnAmerican Activities Committee and the State Selective Service.

Anyway, I fought my case all the way up to the Supreme Court, and they didn't hear it. I'm not surprised. For to hear my case and maintain their judicial integrity, they would have had to acquit me. But in acquitting me, they would also have destroyed two-thirds of the draft boards in the country, most of the draft boards operating in Third World communities. My draft board was not exceptional in terms of its makeup or its operation. It was the general pattern. I didn't give the government a way out. So I knew I was going to prison.

S.E.: Why do so many black men go ahead and enlist in or volunteer for the infantry?

W.C.: I don't buy the thing that blacks are in the infantry because they are unskilled. They're in the infantry for economic reasons. They can make more money there. If you're on the front lines of Vietnam, particularly in the hot spots, you get all these extra kinds of dividends which you cannot get in the larger society. Essentially, the whole inducement even for volunteers is economics. If you look at it from a practical standpoint, most of the black homes in this country were bought through GI loans. Our statistics showed that 85% of all the black homes bought in this country from the time of that loan period through 1969 were bought on the GI loan. And a good portion of all the black males who went to school during that period went to school on the GI bill. Thus, given the racism and the whole economic structure of this country and the way it relates to black people, in essence a black man is more useful to his family, more useful to himself by killing for the rulers of this country or by putting himself in a position of being killed by them.

Also regarding the women in this society, particularly black women, and what they are supposed to be about in terms of fine houses and all the other junk that goes with it, the only way a black woman, in most cases, is likely to get that is through her husband's involvement in the service. So very clearly there is a push on that level for black men to join the service.

In a very real sense, the military is the economic stabilizer of the black family and the black community. It is in fact an economic leveler. And the more economically stable elements in the black community are people who have been involved in the military. That is why there was at one point the high number of reenlistments and also the large proportion of black men in the infantry.

S.E.: Did you find that a lot of men, a lot of black men were conscious of the economic dynamics involved in the draft?

W.C.: Very, very conscious. Before I went to prison in the summer of '70, we did studies in cities across the country, anywhere from 30% to 60% in some cases of all the blacks registered were not showing up for physicals and so forth-a very conscious rate. But, first of all there are no lawyers in the country who understand the black perspective on the draft and I speak from my own experience. Secondly, there are very few lawyers, black or white, willing to go in and battle on the political issues. People don't want to go through a hassle and go to jail. So if they get caught, they go to the Army, where at least they will make some money and get a chance to travel and all the other arguments that go with that. But very few of the young blacks who go in, go in with any attitude that they're going in to fight for the country, or that they're going in to do something for democracy. Most of them are very clear that the economic inducement is what sends them in there. It's a job. And if he's married that's the option. The option for a young black man in this country is the Army, prison, or drugs. You can take your choice.

S.E.: What about the image that the Army projects about being the first truly integrated institution in the United States and that blacks have more mobility in the military than any other place?

W.C.: That's very true. But I don't think the integration argument really induces people. The second one I'll buy. The Army has replaced the corporations in the hiring of black people. But you've got to deal with the fact that in New Orleans right now 85% of all the veterans returned from the war don't have jobs. And with what's happening within the veterans' movement within the city, people stay out a couple of months or a year and no job. Then they reenlist for that very reason. There are absolutely no jobs for large numbers of black people, and they stay in the service for that reason. If the contradictions come they come in that reality, that the Army has only a certain level of job categories for blacks. But even that limited advancement is much better than the civilian economy affords. The conflict in the Army comes from the real fact that it is not integrated, that it is very racist like every other institution in this society.

S.E.: Now, you said the military stabilizes the black community economically, but what about the conditioning that the men go through. In resisting that, do they become members of the progressive element in the black community when they get out?

W.C.: I think two things happen with people going into the service for economic reasons. The Army offers a lot of the extra benefits: For the first time maybe you have a bed of your own. For the first time you have some semblance of privacy. For the first time you travel out of the region of your birth. Those are the very real things to people who have not been able to afford them. Of course, I think that sort of cushions people, initially, to the other reality of the Army-the regimentation, the brutalization of the mind, the racism.

But, if that reality hits him, then he becomes very progressive for the simple reason that he is forced to become so, since his whole attitude from the get go was not in support of the Army as it was to gain the dollar that the Army can afford. What they see in Vietnam is the fact that the people that they killed and the people that they were fighting against, with the exception of the more obvious physical differences, could be your father, could be your mother, your brother or cousin or anybody at home. That in essence the peasants of Vietnam occupy in Vietnam the same role as black people in this country. The reality of shooting your mother is what radicalizes veterans. For that very reason, the Army pushes drugs. I'm sure they're aware of that. The Army attempts to block that reality and to take on its full political maturation by making drugs freely available.

And if a guy is hung up on drugs — the reality of a good portion of black service men, and, I guess, service men in general-he comes out and in most cases stays on drugs. No one begins to deal with him. He gets arrested and goes to prison. Or he becomes a pig.

I'd like to talk about drugs and agents in the black community because I think drugs are very key to understanding that. Clearly drugs are pushed by the United States Government in the service and on the street. The junkies I talked with during my prison experience very clearly say that drugs came to the black community in the massive way they did in 1964. As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, so also did the drug traffic.

Before that period, before '64, the drugs in the community were basically limited to a small segment of the population: the hustlers, the pimps, and the entertainers for the kind of lifestyles that they led. That changed in '64. Likewise, the people who sold drugs before that period were the hustlers — people who sold drugs to support their own habit. Now in the community, most of the people who are selling drugs aren't users. It is very clearly a business. And it is the only business in the country that black people can profit in and profit greatly. I don't know all the figures but in talking to some of the experts at the game, they tell me that it is possible to buy $500 worth of drugs in New York City and in a week's time make $5000. The pushers are businessmen in the black community. It is no longer a question of drug users selling sufficient drugs to support their habit. It is a definite arm of control in the black community.

If you interpret that in terms of Vietnam, the military knows guys are using drugs. They push these drugs, and they let them use them until they're ready to bust them. Then they bust them and give them a choice. You can go to jail, or you can spy on black groups. It's blackmail. Since they haven't had too much of a political consciousness, given the choice of 15 years in Georgia State Prison, they choose to spy. They have not understood in any real sense what their struggle is all about. For them spying on the Panthers or spying on any group like that is not necessarily negative, because they don't really see that the Panthers are going to do too much anyway. I mean that in a general sense. It is not that they don't relate to what the Panthers are saying. They recognize the proportionate power of the the enemy as opposed to the Panthers, especially, in light of their military experience. So that's the other problem you have with the veterans.

S.E.: One of the functions of drugs really is to keep people who come back from telling their story.

W.C.: Exactly.

S.E.: So that the next generation doesn't learn about its experiences.

W.C.: That's why the most important thing any revolutionary can do in the cities of America is to fight drugs. And as far as my program is concerned, I don't see that we can compete with the government. We don't control the force. Obviously, the government brings the drugs in. If it wanted to stop it, it could. As long as drugs are available, people are going to use them, because in essence the euphoria that comes from drugs is much better than the reality of this country. Thus, I cannot see that you're going to make any convincing argument to people saying, "drugs are bad." But you can say, "keep the pushers out." Give them a date to get out. If they don't, leave them in the gutters. If there are no drugs then they can't buy them. That's my policy on drugs.

S.E.: How do you see working with vets in progressive ways?

W.C.: One way that we have worked with them is in just being able to explain the Army's role to younger black men who might get involved in that situation. Vets are very effective draft counselors, but they are also very effective in explaining to people, who go in simply because the black movement cannot provide economic stability to stay out, what they're likely to experience. These people can begin to deal with that situation before it becomes a destructive force. One of the reasons why there are mass rebellions of black soldiers within the service now is the impact of the wave of veterans from the early sixties who came out of Vietnam at the height of the American involvement, and who explained to younger servicemen exactly what that experience was. That is the organizational ability. I am not talking about people going around the country organizing rebellions. From the Vietnam experience, black vets do understand the Army as an institution of imperialism, with a genocidal factor. And right away, as soon as that contradiction hits them, they fight, rather than trying to cushion it with drugs and all the rest.

S.E.: What has happened between say the Korean conflict, which was also military aggression against a Third World country in which blacks participated, and Vietnam? There are several things in-between that, right? A lot of blacks that came out of Korea have been some of the strongest stabilizers to come back into the black community. But that is not the case with black veterans out of Vietnam.

W.C.: Right. One reason for that is that in the Korean conflict there wasn't a strong black movement in the black communities that would challenge some of the basic American values that obviously service men have.

With Vietnam there is a different situation. The Korean veteran came back as an exemplary black man who could make it, as a fabled figure in the black community, sort of like the American father image painted in black. I think he was very much looked up to. The Vietnam veteran comes back to America, to the black community, as a traitor, as someone who has betrayed black people, almost as an enemy.

I don't mean to say we hate black veterans, but his image is not that of a hero. His image is one of someone who killed another revolutionary people fighting against the enemy. It is that contradiction also that has forced them to have to come to grips with what they as servicemen represent. Take the phrase which more than anything else made black people understand the war in a much more profound way, the phrase that was current in the mid-sixties: "No Vietnamese ever called me nigger." That spoke to the reality of the situation that black people had to come to grips with. From our perspective it was the most revolutionary thing we could say. I don't think there was really a black presence until that particular point was made evident. What everybody was thinking in his mind was suddenly codified, and everybody could relate to it.

S.E.: You mentioned using those veterans to inform the community of just what military service means. Do you see other programs?

W.C.: A lot of things you have to almost start before people become GI's or before they become veterans. One thing the black struggle should get into more consciously is the youth movement. I don't know exactly what form it should take, but it must clearly explain on all three fronts the realities for black youth to join the job force, to go to school, or to go into the Army, if you're a man and maybe even for a woman, if the Equal Rights Amendment comes into being. Because I think the struggle is about power. The struggle is about control. All three of those factors are control mechanisms. They really push within the psyches of black people the idea that you are Americans first and foremost, and if you are black people, then your blackness is secondary to that thrust.

I think you can begin to instill in black youth that the American military machine is used to blunt revolutionary struggles the world over. That's why it exists and that's what it will be doing. Essentially, it will be fighting Third World people; probably in the next five or ten years people in Africa. Black youth must come to grips with that. I'm saying it's that kind of program that the black struggle has to get into.

Concerning the GI's in particular, more support must be given to black servicemen to fight the racism within the military and to expose that whole myth of upward mobility. You are more mobile, more sustained economically in the service than in the civilian life, but the myth of upward mobility is clearly there. But just to say that it's a myth is not sufficient, that sort of restrained mobility in the service is much better. You're going to have to go from that consciousness into involvement in the broader issues. I think that comes from consciously involving the black struggle in the military. That means support legally. That means mass education in terms of what the military's impact is economically and so forth. More and more the black struggle has to get into that.

S.E.: What kind of impact, what kinds of changes do you think the volunteer Army will make?

W.C.: I view the volunteer Army in the same way I see the antiwar movement, which prides itself on sort of ending the draft or lessening its impact. To a certain extent it can claim credit for that, but I really question on what basis it ended. Like I said, the draft moved from white middle class America into the black community, the Chicano community, the Puerto Rican community, and to the poor white community, too, in the South. Nonetheless its impact has been national on the black community, not just limited to a region which more or less in the country for whites has been in the South or in certain areas of the South. Whereas, for black people it has been a national impact, a genocidal impact.

Just looking at the volunteer Army from the standpoint of what a soldier is likely to make, the figure is anywhere from $500 to $700 a month. I don't know too many civilian jobs that pay that to a black man which means, essentially, that the proportion of blacks is likely to be higher within that voluntary Army than they are in the other. Except, I don't feel that imperialism can get enough people to fight a hot conflict. As long as things sort of stay like in Vietnam, where they got Vietnamese killing each other, and they have a fairly automated battlefield, they can get by with that kind of Army. But as soon as things flare up again (and they're gonna flare up), the contradiction between capitalism and the people it oppresses are clearly going to resort to that kind of situation. They'll have to use the draft again. If the black movement, in particular, and the left movement, generally, has developed a broad presence on the impact of militarism, I don't think it will be possible to draft people in those large numbers again.

I think Vietnam has been a lesson to the country in a far more profound way than the left movement sees it, you know. I find it to be the most radicalizing experience in the black community in terms of just recognizing very consciously that the conditions of black people in this society are, first of all, related to the conditions of oppressed people the world over; secondly, that those conditions result from the way this society is organized and from the kind of political and economic decisions that come from that organization. It is no longer going to be the issue to get a black foreman or a black school principal or what have you. The issue is ultimately control. That means, essentially, fighting to control every facet of institutional life in America. I think Vietnam has done that for large numbers of black people.

S.E.: In thinking about conversion of the military, it seems like we must think in terms of the whole political economy, of building alternative economic units which can both support us and alter existing institutions. If you have an economic cooperative that can take-over, or demand the use of a military installation for economic development, that whould be the kind of program which could undercut the base of the military.

W.C.: I accept that. I didn't know that the Left was organized in a way, or people were organized in a way really, to force those bases to become that. Look at what's happening with military institutions. Either they revert to some other government agency and become counterinsurgency things rather than overtly military, or I understand a lot of them might become prisons. I see some of that within the Bureau of Prisons, like at Maxwell Air Force Base where part of that is a federal prison camp. The same thing is at Eglin Field. Part of that is a prison camp. And they are toying with some of the ones out in California in the same way. I know it's a model to see if it can work, but if they feel that's viable, then a lot of that might also happen.

In terms of conversions of the military, I think that people who use that term or think about that don't want to struggle, because they feel that somehow we can through the democratic process take the machine from the monster. I don't believe that. In its essence the military in this country is a counter-revolutionary tool, and it's going to be used that way. The only conversion that is going to come is when you have an armed struggle and people are going to do battle with the military. Even to think in terms of conversion without that doesn't make sense to me. They're not going to dismantle the military. They're just going to dismantle those institutions that they don't need because they have found a different way to fight or something or other.

You have to talk about building up a base for struggle within the military which will literally fight on bases in that way. That's the only way. They're not going to say, "Oh, I think war is horrible. I think imperialism is horrible, and, therefore, I'm going to convert it to something else." They don't think imperialism is horrible. I don't like to look into the future too much, but I think what's going to happen is a continuation of what happened in '68 in Vietnam. In '68 there were more skirmishes between officers and enlisted men and between black soldiers and white soldiers than there were between American troops and Vietnamese. Basically, the same thing is going to happen inside the military, period. At that point you'll have a force on the inside and the outside that is battling for the same things. The military, essentially, has to turn on its own people.

S.E.: I'm wondering whether the contradictions for whites in the military are at the point where effective black and white alliances can develop?

W.C.: The contradictions for whites in the military are the same, as the contradictions for the blacks in the sense that if you're not an officer or of the officer class, then you're shit on. But at the same time, it is also the separation from having lived in the larger society that you consciously bring with you to the military. I don't think the forms of how to overcome that separate development . . .

S.E.: Between black and white?

W.C.: . . . right . . . have been developed enough that you can really begin to see unity on the other thing.

S.E.: The basic struggle is going to be around racism?

W.C.: More or less, if for no other reason than there is no white force that you can find to join with, because they have not come to grips with their racism. And they can recognize the contradiction between officer thinking in the military as in the larger society. The officers more or less move away from attacking any white folks in a mass way. They attack black folks and single out a few individual whites. Those are clearly the whites who are much more aware and, obviously, challenge them on a lot of things. But by and large, the contradiction of the military is the contradiction of being enlisted as opposed to being an officer and all that that means. At the same time, however, you have the other matter of having come from separate communities. You've had two separate existences basically, and all of a sudden you're thrown into the military together--I won't call it integration-with all of those values that you've developed that way. I think blacks in the service are more concerned about survival. Trying to build anything with white people sort of becomes secondary. I don't know if there are many whites within the service who are dealing with the racism.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.