Tennessee attorney and advocate Keeda Haynes on bending the arc toward justice

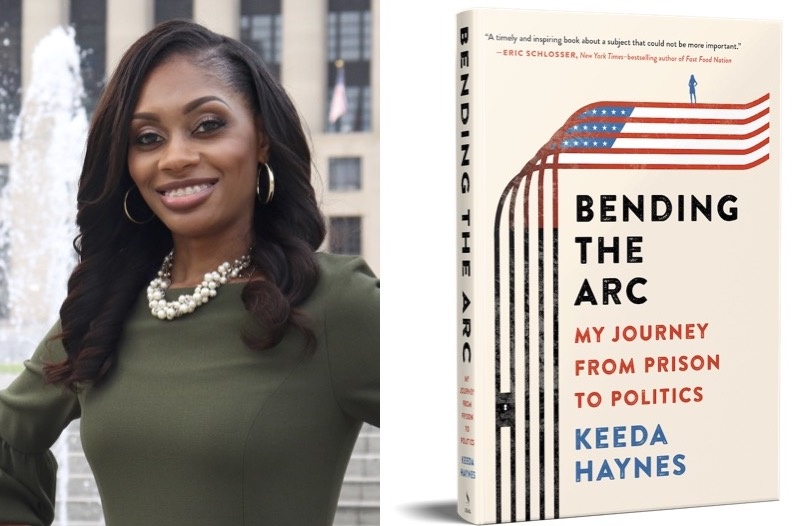

In her new book, Tennessee attorney and advocate Keeda Haynes points out that what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called "the moral arc of the universe" does not bend toward justice on its own. (Haynes' photo via The Sentencing Project website.)

In her recently released book "Bending the Arc: My Journey From Prison to Politics," Keeda Haynes of Nashville, Tennessee, uses her personal experience to paint a picture of the brutality of the criminal justice system and the so-called "war on drugs."

A former public defender who now serves as the voting rights campaign strategist for The Sentencing Project, a national criminal justice reform group, Haynes made headlines in 2020 when she ran in the Democratic primary for Tennessee's 5th Congressional District. She won 40% of the vote with a progressive campaign against longtime incumbent Jim Cooper, who's part of the conservative Blue Dog Coalition. Even though Haynes lost, her campaign inspired many people, some of whom had never seen a formerly incarcerated person run for such a high office — especially in the South.

Haynes offers a personal account of being caught up in the war on drugs in Tennessee — one of the most carceral and disenfranchised states in the country. Her proximity to what she calls the "criminal legal system" helped her be a stronger voice for her clients and inspired her run for Congress.

The title of her book is based on the famous Martin Luther King Jr. quote that "the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice." Haynes points out that the arc does not bend on its own, so it's up to us to do the work of bending it.

Facing South recently spoke to Haynes about the book and her work. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You first made national headlines back in 2020. This was one of the first times — if not the first time — that many people had seen a formerly incarcerated person run for such a high office. Why was this type of representation so important?

At the time when I ran for Congress, I had been a public defender for a little over six years. In that process, the clients I was representing were the people that the community considered to be the least of these.

I wanted to be a public defender to change the system, but being in that part of the system I saw that there were just so many things that were happening in my clients' lives outside of the criminal legal system that nobody was dealing with.

What do you do when you ask your client if their drug of choice is one drug, and they say, no, it's actually this drug, but I'm using this one because it's less dangerous to step down from what I'm really addicted to, because I don't have health care to go to a treatment center? What do you do when you hear that people don't have jobs, or they're underemployed, or that they don't have health insurance — and it's a combination of these things that's leading them into the criminal legal system?

That was one of the driving forces with me. I wanted to run for Congress because I felt that we deserved better than who was representing us. We deserved someone who was going to fight for us and fight for our issues that we were dealing with in the community. I felt that I was the best person to do that because of not only my work as a public defender but the advocacy work I was doing in the community. I felt like I was the better person to be able to advocate for Nashville in Congress.

In your book you talk about being a wrongfully convicted person. But you also make it clear that the criminal legal system is unconscionably harsh even for those who are guilty of the crimes that they have been convicted of.

We see that now with a lot of the criminal justice reform that is taking place — people have started to realize that.

When I was incarcerated, you had the federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws. They still are in place, but not to the degree that they were then. I was subjected to a mandatory minimum sentence of five years simply because of the amount of marijuana that was charged in my indictment. There were women who were in prison with me who had 10-, 15-, or 30-year sentences — all for selling drugs.

I don't believe that anything bends toward anything on its own. It doesn't just happen. We have to do the work that's necessary in order for it to bend.

You hear people say someone killed someone and got less time than that — and that is absolutely true. Here in Nashville, we had a white police officer who killed a Black man and is serving three years for taking a life. Whereas we were giving people 10, 15, 20 years for selling drugs. At the time there were so many people who were being brought into the criminal legal system and being sentenced for conspiracy. This was at the height of the drug war.

A lot of that is what I have been speaking about — the mandatory minimum laws that were in place and still are in place that cause people to have to be in prison way longer than any person should have to be for the offenses that they are charged with.

In your book you talk about the "adultification" of Black girls and how they and Black women are seen as more susceptible to certain crimes. I think about you, but also women like Breonna Taylor of Louisville, Kentucky, who was presumed by the police who killed her to have been involved in a drug operation even though that was never proven.

There is an association with Black people and criminal activity. In the legal community you hear "innocent until proven guilty," but you will also hear people say "guilty until proven innocent."

A lot of times you are not even able to prove that you're innocent — and why should we have to? There's this association that you wouldn't be charged with this if you hadn't done something. Like with Breonna Taylor — she had to have done something. In reality, she had actually done nothing.

In my case, the prosecutor likened me to a prostitute. There's this whole criminality that is associated with Black women. In this legal system, it's "you had to have done something." This country has a history of that — in the way that Black people, Black women, are treated in the criminal legal system, all because of the color of our skin. That's something we don't talk about as much, but it definitely happens.

And I saw it happening while working as a public defender. My Black clients were automatically guilty of something because they had been arrested and the police said so. But with my white clients, the district attorneys were more willing to consider that they may not be guilty.

With what I had been through, I had the duty to call this out for what it really was and to let the DAs and judges know that this was a bias that they had against this client.

One reason why you were able to recognize this disparity was because you had proximity to it through your lived experience. Many of those in power do not have this proximity. What can be done to bridge this gap — for people in power like the judges and DAs to have more empathy for those they're making decisions about?

You have to listen to people who have experiences. You have to be willing to do the necessary work in order to change.

I can tell people what is wrong with the system all day long, but unless judges and DAs and those who are in positions of power do the necessary work in order to change themselves, the system will not change.

Also, if I choose to educate you, that's fine. But we should not put it on the very ones who have been oppressed in the system to teach you what is wrong with the system. We should not be doing that.

The title of your book comes from the Dr. King quote where he says, "the arc of the moral universe is long but bends toward justice." What do you think it will take for that arc to bend?

You will notice that the title of the book is "Bending the Arc" — I-N-G. That's a verb. It means that there's action behind it. It means that we have to do something.

I don't believe that anything bends toward anything on its own. It doesn't just happen. We have to do the work that's necessary in order for it to bend. Nothing bends without us first bending it. That's why it's called "Bending the Arc," and that's why, in the book, the work continues.

We have to constantly put pressure and do the necessary work in order for this arc to bend toward justice. Without it, it's never going to.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.