Medicaid expansion could be a lifeline for rural hospitals in the South

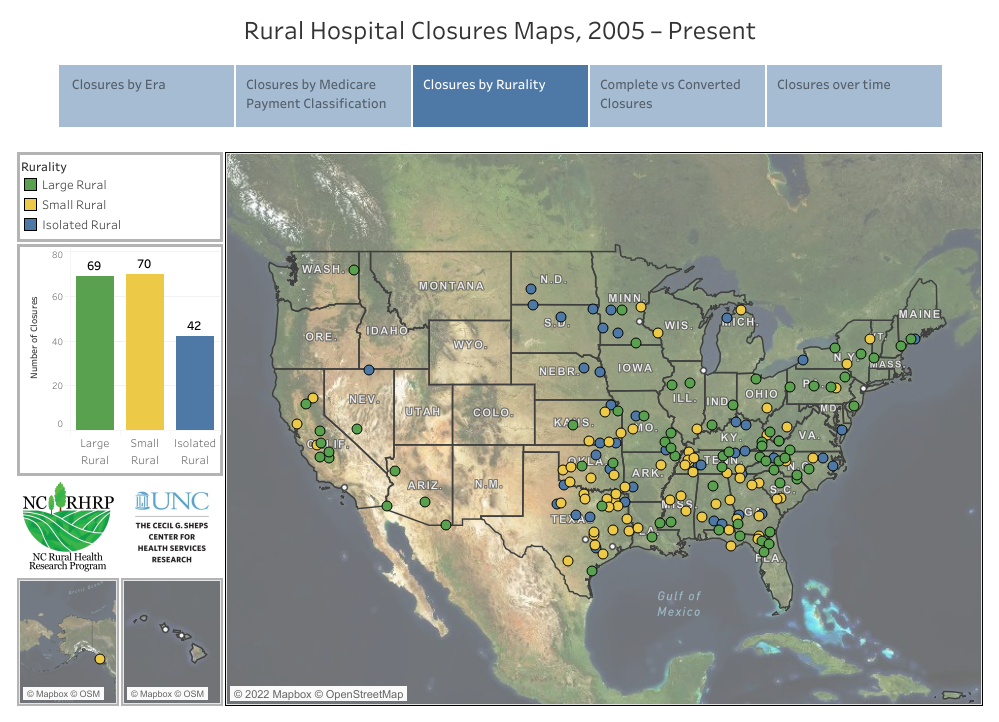

(Map via the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)

The coronavirus pandemic devastated rural hospitals in the South initially, with 13 of them closing in 2020 alone. But federal pandemic relief sustained hospitals in rural communities last year. No rural hospitals in the South closed in 2021, and only two closed nationwide.

However, special pandemic funding for hospitals in rural communities is running out and some is expected to expire at the end of this year. Meanwhile, the omicron surge is worsening the medical industry's staffing shortages. Health care advocates say expanding Medicaid in the region could help rural hospitals stay afloat and provide needed care. To date, 38 states and Washington, D.C., have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and 12 states have not, with eight of the non-expansion states in the South. The non-expansion states have seen more rural hospital closures.

"The data has shown a tremendous positive impact to rural facilities in states that have expanded Medicaid," Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association, told Facing South.

The two rural hospitals that closed in 2021 were in Illinois and Kansas, according to data from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Sheps Center, which tracks rural hospital closures across the United States, found that 181 rural hospitals have closed since 2005.

Southern states have seen the most hospital closures over the last 17 years, according to the Sheps Center. There have been 24 closures in Texas, 16 in Tennessee, and 11 in North Carolina — all Medicaid non-expansion states.

Over the past two years, rural hospitals received lifelines from the pandemic relief programs approved by Congress. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided $100 billion to the health care industry, and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided $398 million last year to over 1,000 small rural hospitals for COVID-19 testing and prevention.

The ARPA funding was especially important given the low vaccination rates in rural communities, which are often poorer, older, and have more uninsured or underinsured residents, according to John Henderson, president and CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals.

"Our hospitals struggled to recruit and retain nurses and primary care physicians even before the pandemic, but COVID has only exacerbated those issues," Henderson said.

George Pink, a senior research fellow at the Sheps Center, also pointed to the ongoing staffing crisis in rural hospitals and beyond. "The turnover is high, and they're very tired," Pink said. "Finding people, finding nurses, finding support staff, finding advanced practice providers who are not sick and are able and willing to work in hospitals I think has to be the most significant challenge facing rural hospitals, and more urban hospitals as well."

ARPA provided fiscal incentives to encourage states to expand Medicaid, but no state has newly expanded the program under the legislation.

Federal lawmakers have introduced two bills recently that aim to proactively address the rural hospital closure issue. This month, Rep. Sam Graves, a Missouri Republican, and Rep. Jared Huffman, a California Democrat, co-sponsored Save America's Rural Hospitals Act, which among other things would extend payments for low-volume and Medicare-dependent hospitals and provide $15 million in grant money for rural hospitals. The bill would also make permanent increased Medicare payments for rural emergency medical services.

And in November, Democratic Sens. Tim Kaine of Virginia, Jeff Merkley of Oregon, Jon Tester of Montana, and Tina Smith of Minnesota co-sponsored the Rural Health Equity Act, which calls for the creation of an Office of Rural Health within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The office would refine policies and best practices to help rural hospitals improve care for their patients. The measure was also introduced in the House by Rep. A. Donald McEachin of Virginia.

Neither of these bills have moved yet. But given that the pandemic has no end in sight, advocates expect pressure will build for rural hospitals to get additional federal assistance.

"I think the great concern is going to be the third and fourth quarter of this year going into next year," Morgan said. "When these federal funds run out, will there be another round of investment by the federal and state governments into these rural facilities, or are they going to be left holding the bag at the end of this year for an uninsured population in many of these Southern, rural communities?"

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.