Pauli Murray documentary shines light on an overlooked trailblazer

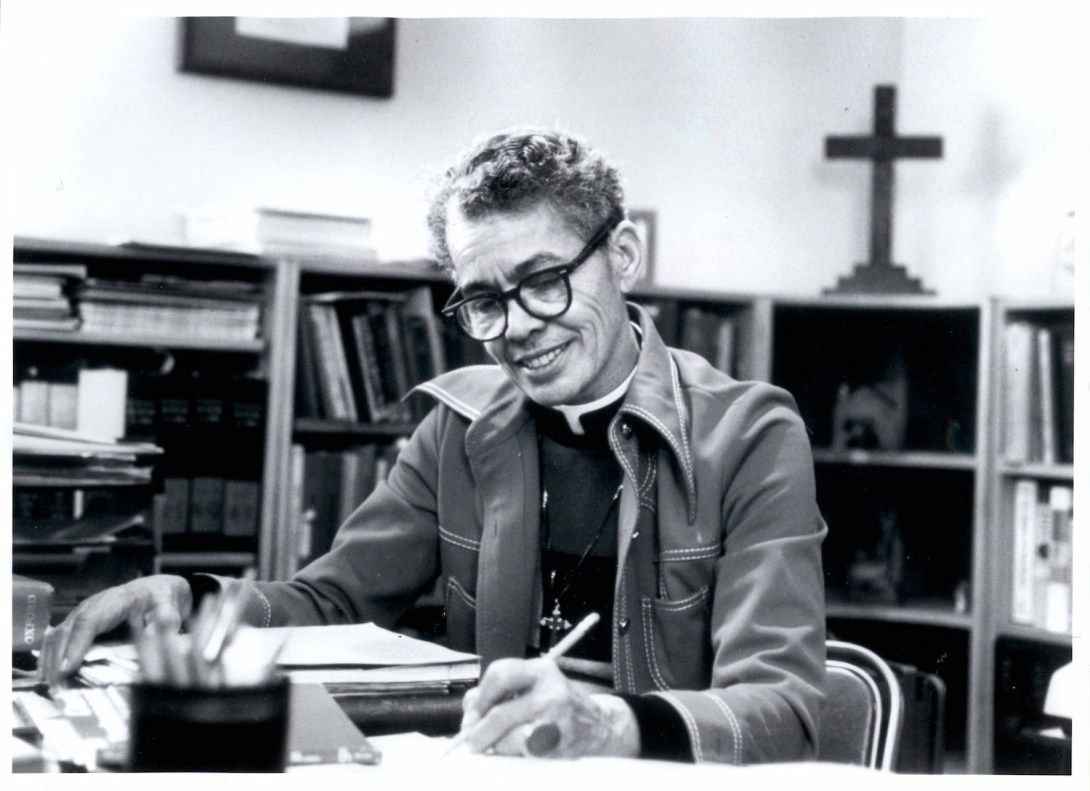

A new documentary is bringing the story of the remarkable life of attorney and advocate Pauli Murray, who grew up in North Carolina, to a wider audience. (Photo from The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History.)

Although Pauli Murray was born in 1910 in Baltimore, the lawyer and advocate who later became the first African American perceived as a woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest was raised in Durham, North Carolina by an aunt and other relatives after being orphaned. Murray's mother died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1914; Murray's father, a public schoolteacher and principal, suffered from typhoid fever and related depression and was murdered by a white guard at a mental hospital in 1923. Murals are dedicated to Murray in Durham, and the late lawyer's childhood home in the city, deemed a national landmark five years ago, houses the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice. Murray died in 1985 and was permanently added to the Episcopal Church calendar of saints in 2018.

But Murray has only recently started to gain wider recognition, and a new documentary wants to introduce the trailblazer to a bigger audience. "My Name is Pauli Murray," now in select theaters and available for streaming on Oct. 1, chronicles Murray's roles in influencing civil rights and feminism years before the movements gained traction in the 1960s. For instance, Murray played a role in integrating a luncheonette while a student at Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C.; protested bus segregation before the pivotal Rosa Parks moment; and inspired Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's influential cases using the 14th Amendment to fight gender discrimination in the 1970s. The documentary's creators also detail Murray's struggles with gender identity using the lawyer's own writings as primary sources to gain insight into a queer person ahead of the times. The documentary includes interviews with Murray's descendants, friends, and modern-day LBGTQ+ advocates and lawyers who provide context on Murray the private recluse and Murray the groundbreaker.

Even co-director Julie Cohen wasn't entirely familiar with Murray's accomplishments until she worked on "RBG," the 2018 Academy Award-nominated documentary on the late Supreme Court justice. Cohen and Talleah Bridges McMahon, a producer and writer for the film, spoke separately with Facing South about how they made the documentary, the research process, and what they hope the audience will learn from Murray. The following interview was woven from those separate conversations and condensed and edited for clarity.

* * *

What made you decide to create this documentary on Murray?

Julie Cohen: The documentary really grew directly from the work that Betsy West and I did on the "RBG" documentary about Ruth Bader Ginsburg. It was toward the end of the process of editing that film that we became aware of Pauli Murray, because Justice Ginsburg as a young lawyer had put Pauli Murray's name as a coauthor on a brief that Ginsburg wrote before the Supreme Court — Ginsburg made the argument [but] put Pauli's name on the cover in the coauthor position. They actually hadn't literally worked together on that brief, but RBG was crediting Pauli's earlier development of the idea that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment could be used to secure rights for gender equality as well as racial equality.

We actually hadn't been familiar with Pauli Murray prior to that. It was after "RBG" came out that we did a little bit more research and learned of the really enormous role that Murray had played, not only in the women's rights movement but also in the civil rights movement and the labor movement, and the incredible poetry and memoirs Pauli had written and published, and some of the very ahead-of-the-times activism, and becoming the first Black woman-identified person to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. There was accomplishment piled on top of accomplishment, and we were fascinated to know more about this figure, and also just the question of how did we not learn about Pauli Murray in school.

Talleah Bridges McMahon: I had worked with Betsy and Julie on another series that was on groundbreaking women. They reached out to me after they finished "RBG" to say that they had another idea for another project. When they told me what it was, I was floored. I have to say, I had heard Pauli Murray's name before in the context of feminism, but I did not know everything that Pauli had done. As they were listing all of the things Pauli had been involved with and telling me more about Pauli's background and life experience, I was floored — and also honestly a little angry that I didn't know Pauli's story. The whole fact that Pauli had not received more credit for their contributions just seemed so unjust that I really wanted to be a part of getting Pauli's name further out into the world.

What was the research process like?

McMahon: There was so much. We're not the first people to tell Pauli's story, so we had the advantage of being able to read books that had been written about Pauli and Pauli's own autobiography. But one of my main tasks was to go to the Schlesinger Library [at Harvard University]. This happened over a few trips really just to get a sense of what materials they had. So I spent a fair amount of time going through the archive looking for Pauli's words. We knew we wanted to tell Pauli's story through Pauli's own words, and so I spent a lot of time looking for letters and anecdotes in the diaries, really trying to get at Pauli as a person so we weren't just telling the story of Pauli's accomplishment. We really wanted to be able to flesh Pauli out.

The doc also touches on Murray's younger life, such as being denied acceptance to the University of North Carolina. UNC is still in the news today for scandals such as the denial of tenure to reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones and the call to rename Hamilton Hall, named for a white supremacist. What's your reaction to some students wanting Hamilton Hall to be renamed after Murray even though Murray doesn't have direct affiliation to the school?

Cohen: There are a lot of schools that are named "George Washington High" or "Jefferson High" that don't have direct connections to those historical figures. I actually think choosing to honor a historical figure is a way to help bring their name and their story to the fore, so I'm in favor of doing that in all kinds of places with Pauli's name. I think there's something affirming about getting Murray's name out there, even at institutions that may have rejected a young Pauli Murray. Certainly Harvard's law school rejected Pauli for being a woman in the 1940s, and yet Murray very specifically chose to have the archives housed at Harvard. Maybe every institution that rejected Murray for whatever reason should now name a building Pauli Murray Hall.

How did you decide the best way to tell this story was mostly through Pauli's own words?

McMahon: It's really hard to tell someone else's story right, and to take this on was a huge responsibility. We knew that we would be introducing most of our audience to Pauli for the first time. So when we realized that Pauli had left so much in terms of not just written documents but also recorded interviews and the recorded autobiography, it became a no brainer to us to let Pauli speak to people. We really wanted to get out of the way and let Pauli tell their own story.

I noticed that some experts in the documentary chose to refer to Murray using "they" pronouns, and some used "her" pronouns, or just referred to Murray as "Pauli Murray." Given that Murray was ahead of the times but also not alive when people were able to choose their pronouns, how did you navigate language while creating the documentary?

Cohen: It was difficult. As you see in the film, most of our interview subjects had known Murray and referred to Pauli with she/her pronouns, which Pauli went by in life. In the film itself our interview subjects referred to Pauli with whatever pronouns they chose, and we just decided to make that conversation about pronouns as explicit, as part of the film, so that people understood — to actually explain what the thinking is, because it is obviously a relevant debate. There is perhaps a sadness in understanding that Pauli, who may well have preferred some other pronouns, didn't have that option in life because the time didn't allow it. In terms of when we're talking about Pauli in interviews now, we just try to call Pauli "Pauli" or Dr. Murray, which was basically an option that was explained to us by the ACLU trans rights lawyer Chase Strangio, who's in our film. He said some trans people just use their name as their pronoun. As soon as he said that, it made a lot of sense to us, because "Pauli" is a name that was very much self-chosen. Pauli's birth name was Anna Pauline, but as a young person Pauli very specifically and deliberately chose to be called Pauli.

What was the most challenging part of making the documentary?

McMahon: It's really hard to tell a story of a person who isn't around but also was not filmed a lot during their lifetime. Making a visual story we knew would be really hard. Having the archives was such an incredible resource, because Pauli thankfully saved not just letters but papers and speeches and things like that. Pauli also saved so many photos, and Pauli was also a photographer. We don't really get into it in the film, but a lot of the photos used in the film were actually taken by Pauli. Those photos turned out to be an incredible source for us in telling Pauli's story. The more we worked on the film, the more we realized that we wanted the archive itself to be a character in the film.

How do you think this documentary will inspire modern-day lawyers, advocates, and anyone who is still fighting against racism and for gender equality today?

Cohen: Certainly some of the people in our film talk about the frustration of Pauli's name not being as familiar as it should be. But constitutional lawyers using the 14th Amendment to fight for equality in the current day, many of them are quite familiar with Pauli's work and Pauli's early developments. I think we hope that being part of a movement to help bring this story out there more will increase the extent to which lawyers and advocates connect the work they're doing now to what Pauli did going back to the 1940s. And not just lawyers, but people out in the world — students, young people, activists, and everyone who is part of carrying out Pauli's mission of fighting for a just and equitable world.

McMahon: My biggest lesson while working on this is that Pauli really had a sense of perspective about how long all of these battles could potentially take. Pauli's approach to it was that each generation should do everything they can to move the ball forward. You may not get there so quickly, and you may not win every battle that you fight, but each person needs to do everything they can to contribute to getting us closer to that goal. And keeping that in mind, especially in these times, was really helpful for me — to know that any particular setback doesn't necessarily matter, as long as people keep pushing for change.

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.