VOICES: Southern schools need more, not less, critical race theory

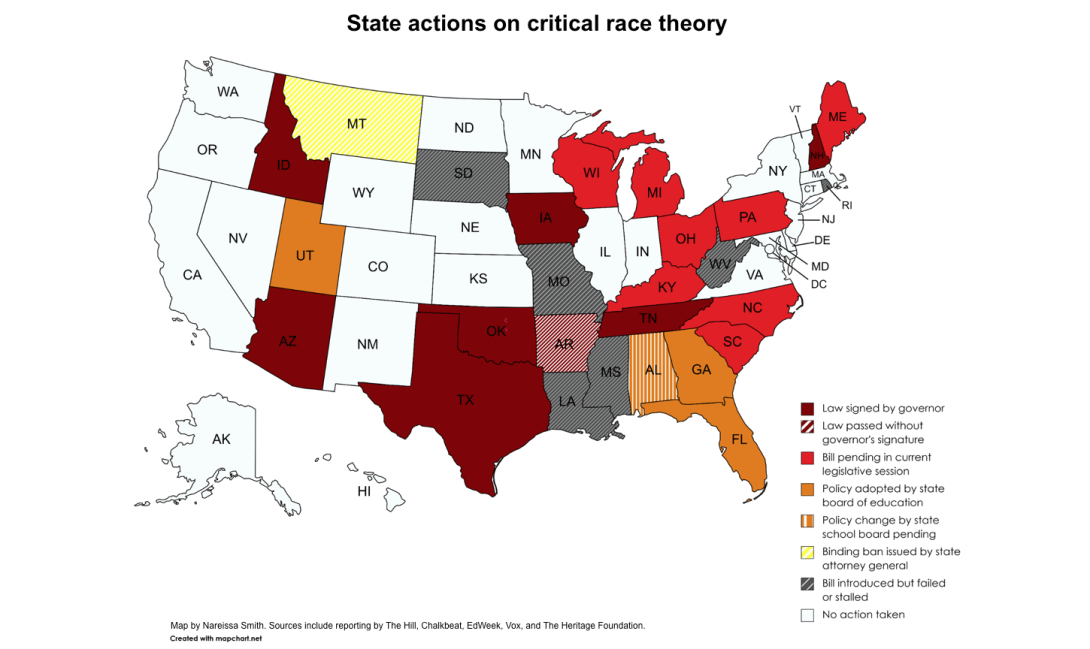

Most Southern states have passed laws or adopted other policies aimed at banning critical race theory from the classroom. (Map by Nareissa Smith)

My eighth-grade history teacher back in Grand Rapids, Michigan, began our Civil War unit with a movie. We spent nearly a week of class time watching "Gone with the Wind." The person responsible for providing us with a true depiction of history showed us a film that elides the true reasons for the war and portrays enslaved persons as dumb, happy, and servile. He gave us fiction rather than fact.

GOP-controlled state legislatures and school boards across the South are perpetuating a fiction of their own. They have introduced bills, passed laws, or adopted policies and resolutions that forbid the teaching of critical race theory (CRT), a concept that teaches students to view the world through the lens of race.

Because of its complexities, students usually study CRT in graduate school, not elementary school. A recent NBC News survey found that only 4% of K-12 teachers use CRT in their lessons. Yet, these bans are still problematic.

In Florida, teachers cannot "distort history" by teaching that America's legal system upholds white supremacy. Georgia's ban doesn't mention CRT by name but bars any discussion that would cause a person to "feel discomfort, guilt, [or] anguish … on account of his or her race or sex." Other Southern states' bans use similar language. While teachers aren't actively using CRT in K-12 schools, the NBC survey also revealed that teachers fear these new laws will make it more difficult for them to lead their students in productive discussions around race. In the South, this fear should be taken seriously.

Of course, Southern states are not the only ones that have passed these bans: States across the nation have attempted to stop the teaching of CRT. But these bans are more prevalent here. They also carry the potential to cause more harm here for several reasons.

First, the South — where most Black Americans live — is the epicenter of African American history. While African Americans have contributed to key events in all 50 states, the South holds more critical pieces of African American history than any other region of the country.

While slavery was legal in all 13 colonies, after the Northern states abolished it, the institution — and consequently, the enslaved population —became concentrated in the South. As a result, the South contains many important landmarks and artifacts relating to slavery.

Many African Americans fled the South during the Great Migration of the 1920s. Those who stayed launched a new fight for civil rights. From the 16th Street Baptist Church to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the South is filled with sites crucial to the Civil Rights Movement. But they will be preserved and turned into public teaching tools only if communities understand their importance.

None of the current bills or laws would expressly prohibit mentioning slavery or civil rights, but they would prevent teachers from giving important context. While preserving white supremacy was indeed one of the motivations for the South's fight in the Civil War, attempts to discuss this in Southern classrooms could lead to accusations that a teacher caused "discomfort, guilt, [or] anguish" in her white students. The same could be said for attempting to explain the racist rationale for Jim Crow segregation.

If these laws proliferate, Southern teachers will be able to take their students on field trips to exciting locations in African American history but will not be allowed to provide them with a full and true explanation of what they are seeing.

Second, the South already does a poor job of teaching African American history. The Southern Poverty Law Center's (SPLC) 2018 report "Teaching Tolerance" examined the social studies curricula of eight Southern states to determine how well they taught 10 key concepts relating to slavery. Georgia, the Southern state with the highest score, taught five of the topics well. At the other end, Louisiana and Virginia only managed to teach one of the 10 topics sufficiently. Though Southern states did a slightly better job teaching about the civil rights movement, there were still gaps. Southern states need laws that support, rather than hinder, the teaching of accurate history.

Third, education matters. White parents start discussions on race less often than parents of color. At the same time, Southern schools — which had been making progress toward integration — are now resegregating at a rapid rate. Without parents to guide discussions on difference or a multiracial group of friends, schools are the primary means for educating white children about racial issues.

Research shows that introducing white children to lessons about racism at an early age reduces negative attitudes toward African Americans. The same research shows that some white children experience guilt after learning about racist incidents. But this is not a bad outcome. As Joseph Flynn of Northern Illinois University wrote in his 2018 book "White Fatigue: Rethinking Resistance for Social Justice," "[W]hite guilt emerges from the feelings that arise when trying to come to grips with the weight and repercussions of historic events, and the crippling feeling that one has no idea of what to do to make it all better." This realization can lead to resentment, apathy, or a passion to fight against these evils. The difference is in whether teachers provide students with the tools to go in a positive direction.

Education matters for another reason. Sadly, hate groups thrive in the South. According to the SPLC, Southern states are home to more hate groups per capita than other states. A correlation exists between hate groups and hate crimes. However, because learning about race improves racial attitudes, studying the themes of CRT in a helpful way could reduce the number of hate groups and hate crimes in the South.

Finally, and most significantly, CRT bans would not only prevent teachers from clarifying the past, but also discourage them from providing necessary context for today's debates. History is more than dates and dead people. History happens in real-time every day.

For example, while Confederate monuments are being removed at a steady pace, over 700 remain nationwide, with the vast majority in the South. If a student asks why these statutes remain, the true answer must contain some references to white supremacy. Without that knowledge, the student will be left with the impression that the Confederates were honorable, if misguided, people.

Similarly, data from Mapping Police Violence shows that from January 2020 to July 2021, Georgia, Florida, and Texas led the nation in police shootings involving African Americans who were unarmed or in their vehicles. If a child in a Southern school asks her teacher to explain why this happens, the teacher's answer would have to begin with slave codes, convict labor systems, and other legal systems designed to maintain white supremacy. But if these anti-CRT laws are in place, the teacher's reply might be muted.

The South has a rich history. Some of that history is ugly and horrific. But with clear guidance from adults, children can learn to grapple with difficult thoughts. Shielding children from racism is like shielding them from death. Though death causes pain and sadness, adults can help children understand it. Acknowledging race, like coping with death, is painful yet necessary. Adults can help children understand racism's messy complexities. To create a bold new future for the South — and the entire nation — we must empower our hardworking teachers to discuss race. We do that by giving them more resources and tools, not by tying their hands.

We must resist any law or policy that would keep teachers from carrying out their core function — providing children with accurate, necessary information and the ability to think critically about it.

Tags

Nareissa Smith

Nareissa Smith of Durham, North Carolina, is a former law professor who currently works as a journalist, history instructor, and consultant. Nareissa's work focuses on racial and gender justice issues. You can follow her on social platforms at @NareissasNotes or @WeThePeopleOfColor.