From the Archives: Chicken empires

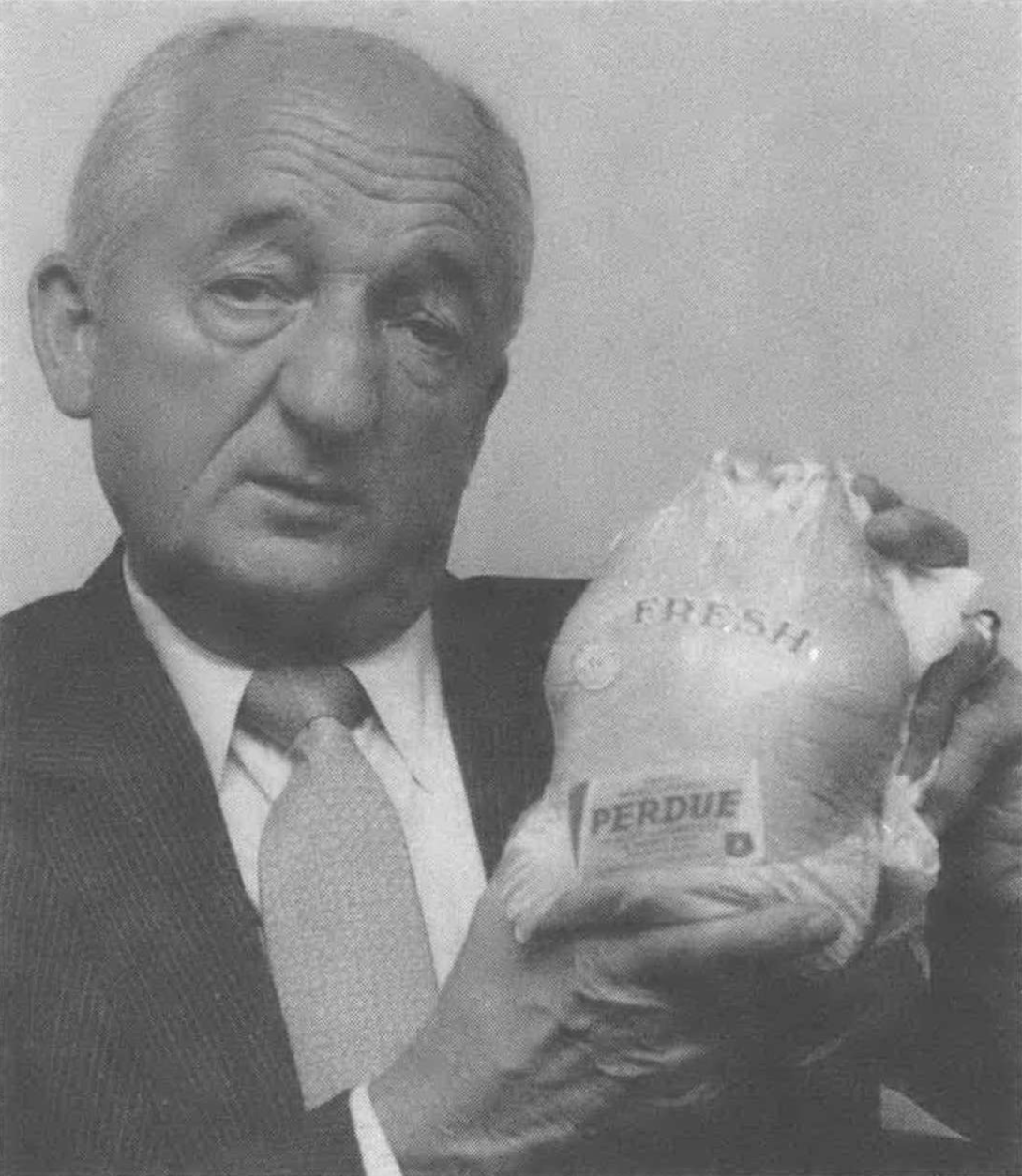

Frank Perdue, one of the early "chicken kings," poses with a packaged chicken. (Photo from the Southern Exposure archives)

This story by Bob Hall was first published in the summer 1989 issue of Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South. It was part of a cover section titled "Ruling the Roost," which investigated the South's poultry industry, then 50 years old and rapidly expanding. The section included six feature stories devoted to industrialized poultry's impact on workers, farmers, and consumers, and won a 1990 National Magazine Award. Thirty-two years later, we are republishing a selection of stories from the issue to highlight what has changed — and what hasn't — since Southern Exposure's initial investigations. Read the other stories, "Inside the slaughterhouse" by Barbara Goldoftas and "I feel what women feel," Bob Hall's interview with organizer Donna Bazemore.

This article is republished as part of Poultry and Pandemic: Meat Industry Workers and COVID-19, a months-long investigative series about the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on Southern meat industry workers. It is published in conjunction with a reported essay by Olivia Paschal on the poultry industry since 1989, and a new interview with organizer Magaly Licolli of the Arkansas workers' justice group Venceremos.

Millions of television viewers have heard Frank Perdue boast, "It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken." Perdue's squawky voice and bird-like face give the slogan a comic appeal. Here's a sincere, down-home guy, we're supposed to think. When he says he puts his chickens through 57 quality checks, or that their yellow tint means something special, we can trust him.

Such is the magic of TV advertising: He plays the clown, and we become fools.

Frank Perdue is nobody's fool — and neither are the 47 other chief executives who manage the nation's $16-billion-a-year chicken industry. Together, these men have transformed a down-home business into tightly-held empires that stretch from Virginia to Texas and beyond. They now control every step of production, from the corn and soybean mills that feed the birds to the processing plants that slaughter and package 110 million fryers every week.

The system once involved hundreds of competing mom-and-pop farms, feedmills, and processors. But in the space of one generation, Perdue and his fellow chicken kings have taken over the entire process from bottom to top. They call it "vertical integration," and through its power — and the magic of marketing — they've turned poultry into the South's biggest agribusiness and one of the fastest growing industries in the U.S.

"We've gone from a very independent, grower-oriented business to a vertically integrated system," says John Wolford of the poultry science department at Virginia Polytechnic Institute. "We've cut out all the middle men in marketing and production."

Thirty years of fierce competition and price-cutting has turned the barnyard into a jungle. In 1960, there were 286 firms selling commercially raised fryers to retailers. Today there are 48. This is survival of the fittest with a vengeance. And Frank Perdue typifies the breed.

Reaching the top

"I grew up having to know my business in every detail," Perdue told a Wall Street Journal reporter. "I dug cesspools, made cops and cleaned them out. I know I'm not very smart, at least from the standpoint of pure IQ, and that gave me one prime ingredient of success — fear. I mean, a man should have enough fear so that he's always second-guessing himself."

Fear has served Perdue well. His company — it's called Perdue Farms Inc., and he controls 90 percent of its stock — is now the fifth largest producer of broiler chickens in the nation, with sales of over $1 billion and a workforce of more than 14,000. It dominates grocery store meat coolers in the Northeast, and it's locked in combat with Holly Farms for supremacy in the Southeast.

To reach the top, Perdue has learned how to sow fear among his competitors and employees, find friends in high places, and intimidate those who would stand in his way of success. Just how tough is a chicken king like Frank Perdue? Two stories offer a clue:

All in the Family. When the United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) began organizing Perdue's largest processing plant in Accomac, Virginia in 1980, the company simply purged its workforce of 55 of the union's strongest supporters. UFCW responded with a national boycott to pressure restaurants and stores in pro-union areas to drop Perdue.

"I guess you can expect retaliation, and I do," Perdue told The New York Times. He courted new outlets for his product and waged a bitter legal battle that ultimately stymied the union. He also sought help from an unusual business partner: the Mob.

In a 1985 deposition to the President's Commission on Organized Crime, Perdue testified that when he entered the New York market in the late 1960s, he resisted overtures from Mafia-related food distributors. One of the largest was Dial Poultry, then controlled by Paul Castellano, reputed boss of the Gambino crime family. But as the Perdue label caught on, he reconsidered. "I started saying to myself, 'Why shouldn't I have some of that business that other people have?'"

So Perdue and Dial began doing business together. Several years later, when UFCW targeted his New York outlets, Perdue turned to Castellano for help. "I knew there was a relationship somehow with the Gambino family," he told the commission. "I just thought, you know, they have long tentacles, shall we say, and I figured he may be able to help." Castellano turned down Perdue's requests not once, but twice.

Perdue now says it was a mistake to seek help from the Mafia. The Crime Commission says his actions illustrate how far some businessmen will go to gain — and protect — a competitive advantage.

Chicken Feed. During the tax reform debate in 1987, the House Ways and Means Committee considered an amendment promoted by Perdue Farms and Tyson Foods, the nation's largest broiler producer. The amendment — worth $500 million to the two firms — would allow them to use an accounting gimmick to keep three years of unpaid taxes because their huge businesses are classified as "family farms."

In a closed-door session, committee chair Dan Rostenkowski announced that the amendment had failed on a 10-10 tie vote. But then Representative Beryl Anthony of Arkansas — home of Tyson Foods and the biggest poultry-producing state in the nation — said "I have Dick Gephardt's proxy. He votes aye." So the amendment passed 11 to 10.

Representatives from farm states less dependent on the chicken kings were furious. "It's a Perdue-Tyson poultry scam," hissed Bill Franzel of Minnesota. "They gave them a half-billion-dollar free ride," added Hal Daub of Nebraska.

Although Perdue is known as a Republican donor, he had given $1,000 contributions to three key Democratic members of the Ways and Means Committee in the previous election. The Tyson family donated even more to committee members. And on a single day earlier that year, they gave $30,000 to two Democratic election committees, one headed by Representative Anthony. All told, the Tyson clan gave $168,000 to congressional candidates and political committees in the 30 months before the vote.

The perfect bird

Tax codes and unions are not the only obstacles that have yielded to the power of Frank Perdue and the other lords of American poultry. This is not just another industry that focuses on profits and products at the expense of people. It is, more specifically, a brazen, still evolving enterprise that stands in two worlds — one evoking the plantation South, the other heralding space-age science.

At the heart of the industry's phenomenal growth is its never-ending quest for the perfect chicken. Each year it spends tens of millions to reduce what it calls "chicken stress." Assisted by more than three dozen poultry science research centers — most based at tax-supported agricultural colleges — poultry companies focus on creating chickens and turkeys with the most meat for the least cost in the shortest possible time.

Researchers spend years developing the ideal lighting to trick hens into laying more eggs with more uniform chicks inside. They test high-tech feed formulas and antibiotic additives that make the birds get fatter faster, without succumbing to any one of a horde of diseases. They recommend weekly temperature changes inside chicken houses to minimize stress. They experiment with genetics, the most efficient watering methods, quick killing and bleeding procedures … they even evaluate which "happy toys" keep the birds most entertained.

Everything is measured in seconds and fractions of pennies. With output expected to reach 5.5 billion broilers this year, an innovation or feed change that saves one half cent per bird will increase income by $27.5 million.

In the past 15 years alone, poultry scientists have sliced two weeks off the time it takes to grow a fryer. In 1940, a chick needed 13 weeks and 16 pounds of feed before it was ready for slaughter. Birds now reach the same market size (about four pounds) in half the time with less than half the feed.

"Today's broiler industry is recognized as one of the world's most efficient converters of feed to food," clucks a new brochure from the National Broiler Council. "Much of this success results from a highly technical, vertically integrated industry using increasing efficient techniques in breeding, feeding, management, disease control, processing, and marketing."

The brochure brags about "computer-assisted geneticists," "pharmaceutical research," and chicken "nutritionists" who "promote optimum growth, uniformity, quality and even skin color." It marvels at the industry's "productivity achievements with clean, modern, mechanized plants."

But nowhere in the brochure is there mention of the people inside those factories. Indeed, the industry's obsession with building a better bird stands in sharp contradiction to its blatant disregard for its employees. Companies bossed by white men seem oblivious to a workforce composed mostly of Black women. They worry about stress on the chickens, yet devote hardly any attention to worker disorders caused by the stress of keeping up with a production line moving at 90 birds a minute. The people who handle the birds are virtually invisible.

In truth, the 150,000 workers in poultry processing plants suffer one of the highest rates of injury and illness in American manufacturing. The rate — 18.5 per 100 employees in 1986 — is twice that of textile or tobacco workers and even higher than miners. Most of the problems result from fast assembly lines, abnormal temperatures, and rapid, repetitive hand motions. They include skin diseases, crippling hand and arm illnesses called cumulative trauma disorders, ammonia exposure, infections from toxins in the air, stress, and back problems.

Poultry productivity has outpaced all U.S. manufacturing since 1960, but the industry ranks as one of the 10 most dangerous in the country. Profits have soared, yet wages remain below average for the food industry. People are eating record quantities of chicken as the healthy alternative to red meat, but the rate of food poisoning from contaminated birds is on the rise.

How could a business that began as a backyard hobby become such an engine of insensitivity and efficiency? The story of Frank Perdue's meteoric rise to fame illustrates the industry's development and its continuing obsession with the bottom line.

From farm to factory

In 1920, Perdue's father, Arthur — or "Mr. Arthur," as he was known on the eastern shore of Maryland, near the Chesapeake Bay — bought 50 Leghorn chickens, built a coop, and started selling eggs to the populous Northeast. Frank was born that same year; three years later, America's commercial chicken business officially began when a farmer a few miles further up the Delmarva peninsula sold her flock of 500 birds for slaughter.

Like a lot of peninsula farmers, Mr. Arthur soon shifted to breeding and raising chickens, but store-bought roasters were expensive — a Sunday dinner luxury — and demand remained modest until World War II. Uncle Sam's huge appetite for a cheap source of protein changed everything. With government-backed research and subsidized growing and slaughter houses, broilers joined a host of other consumer products (from frozen orange juice to margarine) that owe their development to the war.

Most of the early production was centered in the South, where marginal farming communities embraced the chicken business as a savior. Many still tie together today's poultry belt — northwest Arkansas, the Delmarva peninsula, northern Georgia and Alabama, Rockingham County in Virginia, and western North Carolina (see map page 12).

Mr. Arthur took advantage of the growing war demand by expanding his chicken operations with the help of son Frank, who had joined the farm in 1939. But he kept breeding his own flocks and, whenever possible, mixed his own feed rather than depend on the dozens of feed mills that had moved into the Delmarva region to service the booming broiler business. The elder Perdue's early devotion to genetic tinkering and diet manipulation represented the germ of integrated production — and economic independence — that his son and the rest of the industry would soon emulate.

"He was very frugal," Frank recalls. "He believed, 'If I don't owe money, I won't go broke.' He provided a solid foundation on which I could build."

Frank became president of Perdue Farms in 1950, and in 1958 took a leap forward on the road to "vertical integration" by building the company's first feed mill. In case after case — from Tyson to Holly Farms to big grain operators like Cargill and ConAgra — the feed mill became the magnet that attracted farmers and their flocks, and eventually controlled their markets.

Using his mill, Perdue could supply farmers in the region with specially designed feed to grow his breed of broilers. "That was kind of a red-letter day that helped us grow," Perdue says. "Farmers in this area saw we had confidence in this industry and began to grow for us."

The post-war years saw fierce competition and a series of booms and busts for the broiler industry. Hundreds of financially shaky family-owned mills, breeding houses, and processors collapsed or merged. By 1967, Perdue Farms' network of contract farmers and company-owned hatcheries made it the largest supplier of live chickens in the nation. Each week its flocks would be auctioned to nearby slaughterhouses like Armour and Swift, where the birds would be killed and shipped up the East Coast.

"I really didn't want the problems of running a processing plant," Perdue recalls. "Finally, we were forced to get into poultry processing in 1968 because we got too many birds and not enough processors."

By year's end, the company was processing 80,000 chickens a day at its first plant and selling 400,000 at auction. "There was more money in processing," says Perdue, "so eventually we added a night shift and were killing 800,000 a week."

Hawking chickens

In the months before he opened his first processing plant, Perdue began courting grocery store chains and distributors along the East Coast. But his marketing approach differed radically from other suppliers. Instead of treating chicken like apples or beef, which lack brand identity, Perdue promoted his products with his own label. He began with $50,000 of radio advertising. By 1971, when he opened his second processing plant (the one in Accomac, Virginia, which was twice the size of his first), Perdue's face was beaming out from televisions in New York and environs.

He started in New York, he says, because "New York consumers are very willing to pay more for a quality product" and "it was an efficient advertising place." When he learned that Maine growers got a few more cents in New England because their birds' skin had a yellow hue, he added marigold petals and corn gluten to his flocks' diets, then pitched them as more tender and well-fed than his competitors.

"We thought, 'Well, if we can emulate them in producing a yellower chicken, we can get a three-cent premium.' So we started doing that," Perdue remembers.

With his distinctive ads and yellow fryers, Perdue pursued one market after another: New York in '69, Philadelphia in '72, Boston and Providence in '73, Baltimore in '76. Each involved personal visits to distributors and store chains, as well as promotional campaigns that put him up against Cargill's Pearl Bailey in New York and the popular Buddy Boy brand in what became known in the press as "the Battle of Boston." Perdue soon dominated the markets in the Northeast. Sales rose from $58 million in 1971 to $500 million in 1983, and his advertising budget increased thirtyfold.

Perdue had succeeded by following the marketing maxim expressed succinctly by his competitor Don Tyson, chairman of Tyson Foods: "Segment, concentrate, dominate. Find your niche and devote your resources to driving out the other suppliers."

"Frank knows the territory, and he fights like hell to keep it," says Ed McCabe, who handled Perdue's advertising account for years. But competitors say Perdue Farms sometimes fights too hard. The U.S. Justice Department has repeatedly accused the company of threatening to cut off distributors who handle other branded poultry — and of carrying out the threats. Ironically, when Perdue threatened to challenge Justice's jurisdiction on the issue before the U.S. Supreme Court, the department dropped its charges.

McNuggets mania

Perdue's move to promote brand loyalty spurred a broader revolution in the industry. Before the 1960s, nearly all birds were shipped whole from the slaughterhouse to the grocery store, where butchers cut them up or packaged them whole, sometimes with the store label. Today, poultry giants like Perdue have replaced the neighborhood butcher with huge processing units attached to their slaughterhouses.

Cutting and pre-packaging the birds takes more money, but it yields higher profits. The more processed the bird, the less work the consumer and grocery store have to do, and the higher the profit margin for the company. "It takes a substantial capital expenditure, but the margins are good — damn good," says John McMillan, an analyst with Prudential-Bache.

Today, poultry firms are reaping even higher profits from poultry that is "further processed" into chicken hot dogs, deboned breasts, patties, and other products. In 1980, companies turned one in 10 chickens into processed products. With the dawn of Chicken McNuggets, the number leaped to more than one in three.

Don Tyson is king of the McNuggets market. While Perdue and Holly Farms continued to concentrate on supermarket sales, Tyson Foods went after the expanding, highly profitable fast-food and restaurant market, which now accounts for 40 percent of all poultry sales. Tyson is the chief supplier of McNuggets, and observers say his persistent attempt to buy Holly Farms flows from his need for more birds to satisfy — and dominate — the market for processed chickens.

The change in marketing and consumer tastes has come rapidly. Today, only one in eight birds remains whole when it leaves the processor, down from one in two in 1980. Don Tyson says over 80 percent of his company's profits come from products it didn't produce seven years ago.

"A long time ago, we worked to speed up the processing line so we could produce chickens with less labor," he told Broiler Industry magazine. The emphasis now is to have what he calls "price courage — to make a product the customer needs at a price you can make a profit on."

Expand and pollute

Making a profit isn't always easy, even for poultry giants like Tyson and Perdue. Both have withstood bad publicity about processing plants infested with maggots and roaches. Both have endured their tussles with organized labor. And, like a lot of other processors, both companies have run into trouble for their massive discharge of wastewater.

The industry uses an average of 5.5 gallons of water for every bird processed, making it the largest consumer — and potential polluter — in many rural communities. In northwest Arkansas, where the city of Green Forest built a huge facility to treat waste from a nearby Tyson plant, citizens are suing the company for polluting streams and contaminating well water. In north Georgia, citizens successfully sued several poultry firms as public nuisances — only to have pro-industry legislators exempt the companies from nuisance ordinances. And in Virginia, Perdue has been cited and fined repeatedly for fouling a stream near its Accomac plant.

Industry magazines now occasionally discuss effective waste management, but by all accounts nothing has overshadowed Perdue and his cohorts' biggest worry: how to keep up with America's love affair with chicken. For a decade, the future for chicken kings has looked bright, limited only by their ability to hold on to their established markets while slowly moving into new territory.

"There's no end in sight in the demand for chicken," crows Perdue. "When we have more demand than we can supply, what do we do? Fulfill the demand!"

To meet this challenge, Perdue and other large firms have followed a simple pattern: expand production by buying up existing companies, build new processing plants, and contract with more farmers to grow chickens faster and cheaper. The number of farms raising 100,000 or more birds a year has leaped from 2,254 in 1959 to 13,214 in 1982 — and three-fourths of that increase has occurred in the South.

For Perdue, expansion meant moving into North Carolina in 1976, opening a giant facility in the state's northeastern black belt, buying a competitor's smaller plant, and convincing farmers to invest in chicken houses. The company also bought out two turkey processors so it could market gobblers under its brand, and opened a high-tech research facility to test ways to shorten a bird's lifecycle with genetic engineering and chemical additives.

In addition to buyouts and biological speed-ups, leaders like Perdue have expanded production by mechanizing parts of their processing plants and increasing the line speed. Workers who handled 50 chickens a minute in the 1970s now find themselves processing as many as 90 a minute.

For the industry, this human speed-up has given well-financed companies greater control over less-efficient processors. As the weak have been absorbed by the strong, consolidation has also picked up speed. The eight biggest poultry firms now control 55 percent of all broiler sales, up from 18 percent in 1960.

For workers inside the plants, however, speed-ups mean less control: they literally become mere appendages to the machines, performing one or two discrete motions over and over. They are also finding it hard to bargain for better shop-floor conditions. In the late 1970s, for example, Perdue bought four unionized processing plants as part of its expansion on the Delmarva peninsula. He renovated the factories to the new line speeds and reopened them as non-union plants. Workers complained about sore hands and not having enough time even to go to the bathroom. But they had lost the union grievance system to challenge the new work rules and arbitrary enforcement.

"He's out to destroy the union," said UFCW staffer Jerry Gordon, noting that the number of union members on the peninsula had declined by half from the early 1970s. "We had to take him on."

Perdue won the fight — even without help from the Mafia — and he defended his anti-union policy by pointing out that he paid his employees 29 cents more per hour than his unionized competitors. At the same time, Forbes and Fortune estimated Perdue's personal wealth between $200 million and $500 million.

In many industries, increased productivity has provided workers with a higher standard of living. But sharing the profits from the booming chicken business has been one of the last things on the poultry kings' agenda. In 1960, workers received 2.6 cents of the 43 cents a pound that chickens fetched at the store. Twenty years later, they got only 3.3 cents — but chicken prices rose to 72 cents a pound. Their wages still lag behind the rest of the food industry, even though their productivity has skyrocketed and their per-worker contributions to profits keep soaring — it climbed another 33 percent between 1981 and 1985.

With its gushing flow of profits, one wonders why the industry doesn't have the "courage" — to use Don Tyson's word — to slow down its processing lines, treat its workers with respect, give their contract growers a measure of security, and still produce a product people are happy to eat?

Must Frank Perdue and the 47 other chicken kings treat the world as a competitive jungle forever?

"Perdue showed everybody how to really market chickens," says Tex Walker, an organizer with UFCW during its unsuccessful campaign in Accomac. "Now somebody needs to show him how to treat people like human beings."

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.