Bloomberg 2020 organizers sue campaign after layoffs

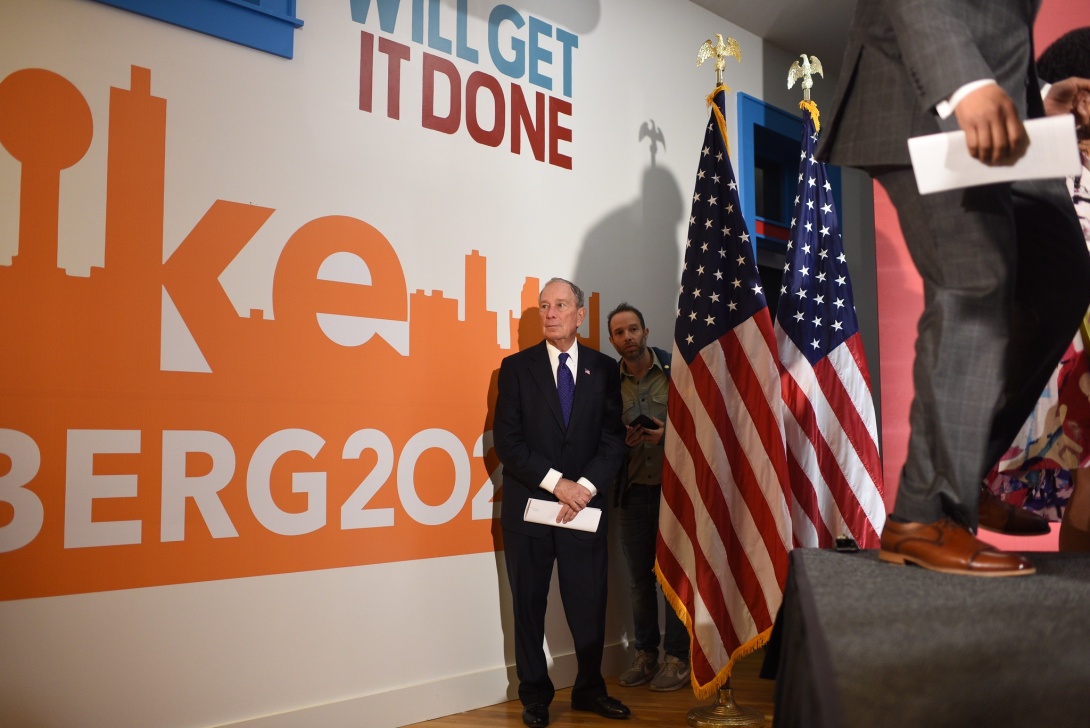

Former presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg at the opening of a campaign office in Knoxville, Tennessee, in January. The campaign laid off all of its field organizers this month. (Photo via Mike Bloomberg on Flickr.)

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg hired over 1,000 staffers nationwide, including at least 698 across 55 field offices in the South, during his short-lived presidential run. The campaign promised the organizers it hired that it would keep them on payroll until November — and it wasn't shy about telling media outlets. Such a promise would be near-impossible to keep for any normal campaign operation but seemed plausible for a man whose estimated net worth is over $50 billion, and who self-funded his long-shot campaign to the tune of nearly $1 billion.

Weeks after dropping out of the campaign, however, Bloomberg broke that promise. He plans to transfer most of his leftover campaign resources — $18 million in funds and dozens of field offices across the country rented through November — to the Democratic National Committee (DNC). But his former employees won't be so lucky. Late last week, in the middle of the novel coronavirus pandemic and related record-setting joblessness, the Bloomberg campaign told field organizers that he was laying them off. They won't see the promised employment through November, and most are slated to lose their campaign-provided health insurance by the end of this month.

But some of them are hitting back. This week, former field organizers in several states including Florida and Georgia filed two separate class-action lawsuits against the campaign in federal court in New York. The suits allege that the campaign lured people away from stable jobs with false promises.

"It is unfathomable to me that Bloomberg spent $900 million on the campaign and he's leaving people without insurance, potentially, during a global pandemic," Sally Abrahamson, a lawyer for one of the plaintiffs, told Facing South. She's representing Donna Wood, who worked for the campaign in Miami. "It's befuddling."

Alexis Sklair, one of three defendants in the other suit, is from Charleston, South Carolina. She had been working on U.S. Sen. Cory Booker's presidential campaign in the state, but found herself on the job market again when he dropped out in mid-January. She didn't lack for choices, the lawsuit states: She had offers from two presidential campaigns, including Bloomberg's, and a state senate campaign that would have almost certainly employed her through the general election in November. But based on the promises that she'd have a job that paid $6,000 a month plus benefits through November, she turned away those other opportunities and moved to Savannah, Georgia, to work for the Bloomberg campaign.

"It is unprecedented for a candidate for president to promise staffers that they would be employed to perform work on a general election and that a primary candidate would keep open his field offices during the general election, regardless of the outcome of the candidate's primary election," the lawsuit states. "But these promises were false."

The class-action suit filed by Wood goes even further. In addition to fraudulent inducement, Wood's suit alleges that the Bloomberg campaign failed to pay overtime, and instead treated field organizers as exempt from federal labor laws that require most employees to be paid time and a half for overtime. Bloomberg organizers, like organizers in most campaigns, often worked seven days per week.

"The exemptions that Bloomberg may try and argue just aren't applicable here," Abrahamson said, noting that field organizers lacked the executive-level job responsibilities usually required to be exempt. Instead, like most field organizers, Wood spent her days making phone calls and recruiting volunteers — hardly high-level administrative work, though the contracts she and other field organizers signed specified that the positions would be classified as exempt.

The lawsuit also alleges breach of contract. Though the contracts signed by staffers were ultimately for at-will employment, meaning the language permitted the campaign to terminate employment at any time, the hiring materials distributed by the campaign promised eight months of paid work that never materialized. A statement provided by the campaign to the New York Times said that the campaign is creating a fund to ensure staffers have health care through April. It also said that staff worked 39 days on average but were given several weeks of severance and health care through March — noting that was "something no other campaign did this year."

Bloomberg dropped out of the race on March 4, following a Super Tuesday showing that was underwhelming for a campaign devoted almost entirely to Super Tuesday states. He won exactly zero states and ended his run with only 58 delegates — meaning he spent about $18 million per each delegate he won. For comparison, former Vice President Joe Biden, the current Democratic frontrunner, has spent around $74 million in total for the 1,215 delegates he has secured, or about $61,000 per delegate. Sixteen days after Bloomberg dropped out, the campaign laid off its remaining field organizers, including Sklair and Wood.

These layoffs came on top of others announced earlier in the month, though at that point staffers were told they would be able to apply for field operations with the super PAC Bloomberg was planning to launch in battleground states including Florida and North Carolina. But after the layoffs of field organizers, it became clear that the super PAC wasn't going to materialize. Former staffers were instead told to consider applying for jobs with the DNC.

Abrahamson says that since filing the lawsuit her firm has heard from former campaign employees across the states where Bloomberg's operation was strongest, including North Carolina and Texas, states where the campaign employed more than 250 people in total. "It's a really tragic time where a lot of people are losing their jobs," she said. "And to the extent that a billionaire could keep people on, and keep people with health insurance, we'd like to see that happen."

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.