State preemption laws complicate Southern cities' affordable housing efforts

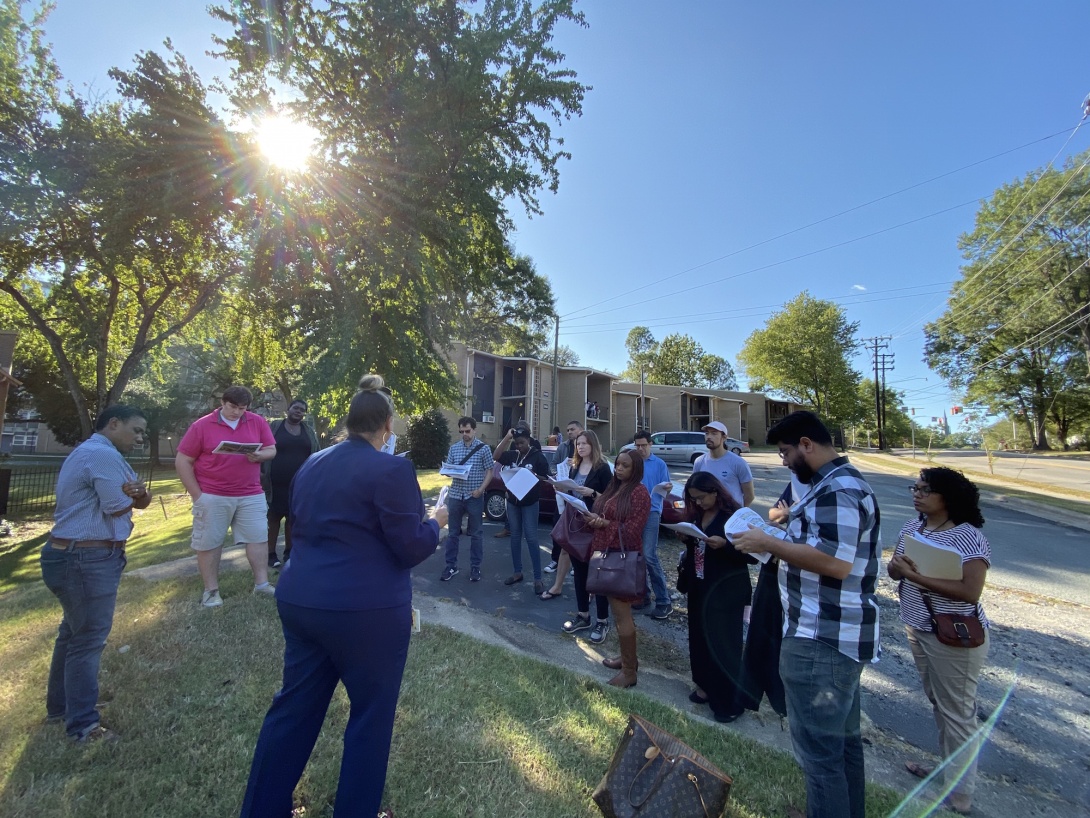

A group of local officials from around the country listen to Meredith Daye of the Durham Housing Authority speak about affordable housing in the city in front of its Liberty Street public housing development. (Olivia Paschal, Facing South.)

This article has been updated to reflect that Delia Garza is the first Latina to be elected to the Austin city council and to correct a transcription error.

The Southern attendees at a recent affordable housing conference held in North Carolina were by and large focused on one thing: how to create inclusive local housing policies in the face of state preemption laws designed to block progressive initiatives.

The summit, which took place in Durham from Oct. 10 to 12, brought together local leaders from across the country. They are all members of Local Progress, a national network of progressive local officials. Most sit on city councils; some are mayors or mayors-elect. Though the attendees represented a diversity of locales, states, and identity groups, they all agreed that affordable housing is one of the most challenging policy areas facing cities today.

"The vision is one thing," Durham Mayor Steve Schewel said during his opening remarks. "The implementation is hard."

It's made even harder by the fact that many Republican-controlled state governments have passed laws in recent years limiting what local officials can do to keep housing affordable. These preemption laws can be traced to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a national group that connects conservative state legislators and business interests. The barriers are particularly onerous in the South, where many state governments have passed laws preempting local initiatives to boost the minimum wage, ban fracking, or limit police cooperation with Immigrations and Custom Enforcement.

State preemption laws have also set up roadblocks for local governments seeking to create more affordable housing.

Every state government in the South, with the sole exception of Virginia, currently preempts local governments from instituting rent control laws, according to the Local Solutions Support Center. Florida, Tennessee, and Texas preempt some forms of inclusionary zoning, which requires new developments to include some units that are affordably priced for low and middle-income households. Florida and Tennessee also preempt some short-term rental regulations, which can help slow the spread of Airbnb and other tourist-targeted rentals into a city's housing stock. In addition, Texas preempts localities from implementing source-of-income discrimination protections used to ensure that landlords don't discriminate against tenants who may be paying for housing with vouchers or other forms of assistance.

"In the housing sector, preemption is complicated," said Katie Belanger, the deputy director of the Local Solutions Support Center. "It's just a tool, not good or bad. It's how preemption is used that can be the problem." But, she added, recent uses of housing preemption, particularly by conservative states at the behest of ALEC, have had damaging effects on some communities. "Preemption in these areas has a disproportionate impact on marginalized groups," she said. "Preemption doesn't just perpetuate inequity, it reinforces inequity."

A housing tour of Durham on the summit's opening day made clear the challenges Durham currently faces, revealing consequences of a history of racist policies that the city council is now seeking to correct. Poverty disproportionately affects minority communities in Durham, where many affordable housing units are old and in need of repair or reconstruction. Mid-20th century urban renewal schemes led to mass displacement in the city's historically black communities, and now gentrification and rising home prices threaten to displace residents of historically black East Durham.

Of course, none of these historic challenges or present realities are unique to Durham. Redlining, urban renewal, segregation, and displacement happened and continue to happen in cities across the country. And as some city councils become more focused on equity, they're having to think about ways to confront their history while avoiding the mistakes of the past.

"We want to create good policy, you know, you want to reach certain outcomes, but we have to be mindful of the things that we thought were good ideas in the past," Vernetta Alston, a Durham city councilor, told Facing South. She pointed to the city's history of urban renewal, which resulted in the almost complete demolition of the historically black Hayti neighborhood near downtown. As Durham confronts a fast-growing population and resulting gentrification, its progressive-dominated council is trying to figure out how to make equitable housing policy, a goal made more difficult because so much of the city's recent development boom occurred without a plan for preventing displacement.

"The housing crisis that we're seeing is one of the direct consequences of all of the economic development work that the city and private industries and Duke University did in downtown Durham," Jillian Johnson, Durham's mayor pro tem, told Facing South. "None of those organizations really had a plan for managing any downstream impacts on community surrounding downtown. And so now we're trying to figure out how to manage those effects on the back end, which is really hard."

Prioritizing equity

Gentrification and displacement are primarily problems in central cities and downtowns, according to a recent study from the University of Minnesota Law School. This displacement is driving a new era of economic segregation, particularly in the South, in which poverty is concentrating in the suburbs. The study found that Southern cities thus far have managed to avoid the high levels of displacement that plague large cities on the coasts. But as population booms threaten low-income and minority communities in places including Durham, city councils are trying to get ahead of the crisis.

"Too many times we're just reacting," said Canek Aguirre, a city councilor in Alexandria, Virginia, speaking on a panel about renter protections. "We want to get ahead as much as possible. In a preemptive state like Virginia that's the only power we have." Alexandria's housing prices are already beginning to rise in anticipation of an influx of wealthier renters moving in to work for Amazon's new headquarters, which will be built in nearby Arlington.

With an affordable housing crisis just over the horizon, local officials are having to find innovative ways to counteract rising home prices and the realities of displacement. And they're starting to strategize.

Colby Sledge, a city council member in Nashville, Tennessee, said he advocates for cities to use their budgetary power to support organizations doing the work that the state bars local governments from doing. He noted that Nashville's city government has passed new regulations on short-term rentals like Airbnb, which are encroaching on the city's housing stock. But he expects state lawmakers to undercut much of that work as soon as the legislature is back in session. They did the same thing in 2018, when the city passed an ordinance designed to force investor-owned short-term rentals out of residential zoned neighborhoods.

Sledge says that, rather than sitting back and allowing states to run roughshod over affordable housing efforts, cities can step in in other ways. "We have to start thinking about using our budget as a moral document," he told Facing South. "We may not be able to legislate this to the full extent we might like or think is most effective. But if we can support that through discretionary funding, then I think it creates opportunity to build that capacity."

In New Orleans, which is facing gentrification that's driving up property taxes and displacing residents, an amendment on the ballot in this month's primary election would have allowed the city to exempt some homeowners from property taxes. It ultimately failed in a statewide vote.

Next door in Texas, a population explosion in Austin has driven gentrification into historically redlined neighborhoods, particularly East Austin. The capital city's urban core has become whiter, and the spike in housing prices has resulted in Austin having one of the highest rates of low-income displacement in the South. A 2018 report commissioned by the city council found that unless the government acts soon, Austin's low-income minority communities will continue to face displacement and loss of opportunities.

Austin is also dealing with a history of policies that have contributed to segregation and economic inequity. Until 2014, for example, all of Austin's city council seats were elected at large, which diluted the power of communities of color. But in 2014, the council switched to district-based seats, which resulted in the election of the first Latina, Delia Garza, to the council, though the city had been majority-minority for nearly a decade.

"I really believe that is what changed the conversation and has prioritized equity and social justice issues," Garza, now the mayor pro tem, told Facing South. Since the change, the city council has started to think about ways to nip displacement in the bud. "We have a pretty good bloc of seven votes that understand the importance of growing sustainably, but also realizing that we have to be careful about displacement and gentrification," she said. "We need to dial down on certain things, certain policies, so it doesn't spur displacement."

Texas law prevents Austin from instituting bans on source-of-income discrimination and from some types of inclusionary zoning, which can make crafting affordable housing policy difficult. But last November, Austin voters approved a $250 million affordable housing bond, the largest in the city's history. It includes appropriations for land acquisition, rental housing development, and home repair funds for low-income residents, among other things.

Voters in Durham will weigh in on a similar bond this November. The $95 million bond would provide funds for the city's five-year housing plan, which includes money for building new affordable rental units, preserving existing ones, and keeping low-income renters and homeowners in their current communities.

"Durham has benefited a lot from the growth downtown. The amount of resources that we have now in this community is incredible," Johnson, Durham's mayor pro tem, told Facing South. "But a lot of people are being left out, and the people who've been left out are the people who are most likely to be left out of any positive trends that we see."

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.