School secession movement drives re-segregation

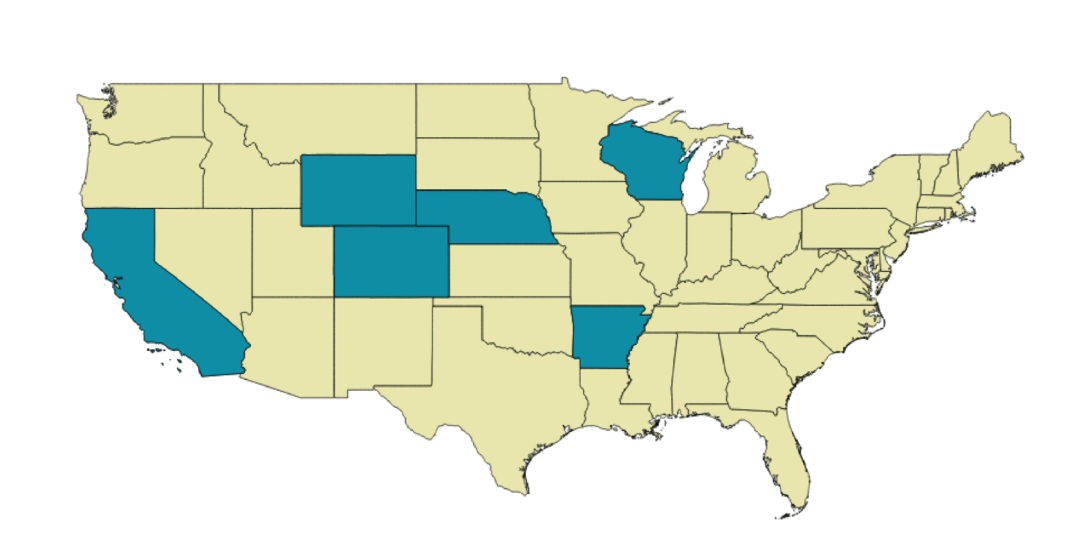

Only six states nationwide require consideration of the racial and socioeconomic impact of school district secession, with Arkansas the only one in the South. (Map via EdBuild.)

Re-segregation is on the rise in American schools. Black students in the South are less likely to attend a majority-white school today than 50 years ago, while black and Latino students are attending schools more likely to be predominately non-white and low-income than their white peers.

Contributing to this troubling trend are school secession efforts, in which largely white and wealthy communities are breaking away from more integrated school districts to establish their own, often justifying the move as a way to maintain local control over education. Since 2000, more than 120 communities nationwide have attempted to secede from their school districts, according to a 2017 report by the education nonprofit EdBuild. At least 47 did secede, taking with them millions of dollars in property taxes. Those secessions took place in 13 counties across the U.S., seven of them in the South.

Earlier this month in Louisiana's East Baton Rouge Parish, for example, residents voted to split from Louisiana's capital city of Baton Rouge to create the new city of St. George. The move came after a failed campaign by largely white and affluent residents to create a new school district. While the population of East Baton Rouge Parish is 47 percent black, St. George's will be just 12 percent black.

As a consequence of the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education ending racial segregation in public schools, the East Baton Rouge Parish School System had been subject to the nation's longest desegregation order, which lasted until 2003. The new city will still have to get legislative approval to create a separate school district, which voters will need to approve at the state and local levels.

Critics see a racial angle in the decision to split from the city and larger school district. "Definitely race is a part of this equation," said Sharon Weston Broome, the mayor-president of Baton Rouge. "We can talk all around it, but it's very obvious — look at the district that's been carved out."

Indeed, the segregationist effects of school secession have been documented by a growing body of research. For example, a study published last month in AERA Open, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association, found that segregation between school districts, as opposed to within them, accounted for 70 percent of all school segregation for black and white students in 2015, up from 60 percent in 2000.

"Our findings show that after district secessions, students are increasingly being sorted into different school districts by race," said study co-author Erica Frankenberg, a professor of education and demography at Penn State University. "Given the relative scarcity of students crossing district lines, the implications of this trend are profound. School segregation is becoming more entrenched, with potential long-term effects for residential integration patterns as well."

In one of the most extreme cases of school secession, six suburban towns in Shelby County, Tennessee, split from the newly consolidated Memphis school district in 2014. Following the move, Shelby County schools had to slash spending, close schools, and lay off hundreds of teachers. At the same time, the suburban towns faced challenges with funding and facilities as they scrambled to build new systems.

Of the 30 states that have explicit policies allowing the splintering of school systems, 10 are in the South. Besides, Tennessee, they are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. Tennessee has one of the most permissive secession laws, according to the 2017 EdBuild report. It allows a municipality with at least 1,500 students to secede without the approval of the district it leaves behind, and without considering the racial or socioeconomic effects. About half of the students in the new school districts near Memphis are white, compared to just 7 percent at the county level.

Not all school secession attempts have succeeded, though. For example, last year a federal appeals court ruled that Gardendale, Alabama, a suburb of Birmingham, can't form its own school system. It agreed with a lower court's finding that there were racial motives in the attempt to split from the Jefferson County system. Gardendale is 88 percent white, but its schools are now 25 percent black because students are bused in from North Smithfield, a predominately black community a few miles away.

Allowing school secession is being discussed in North Carolina. In 2017, the Republican-led legislature formed a study committee to consider breaking up school districts including Wake County's and Charlotte-Mecklenburg's, the state's two largest. Wake County had been a leader on school integration; in 1976, the mostly white county and mostly black Raleigh city school systems merged to achieve integration despite widespread opposition in the community. The merged district worked to balance schools racially and economically through a combination of busing and magnet schools. But in 2009, a new Republican school board majority ended the district's integration efforts. Though Democrats regained control of the board in 2011, the district still struggles with finding ways to promote diversity in its schools. Secession would only intensify that trend.

"It's becoming much more difficult to maintain integrated schools, and in fact our schools are re-segregating and we see that in the data," said Wake County Schools Superintendent Cathy Moore.

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.