Low-wage workers gather to build power across sectors in the South

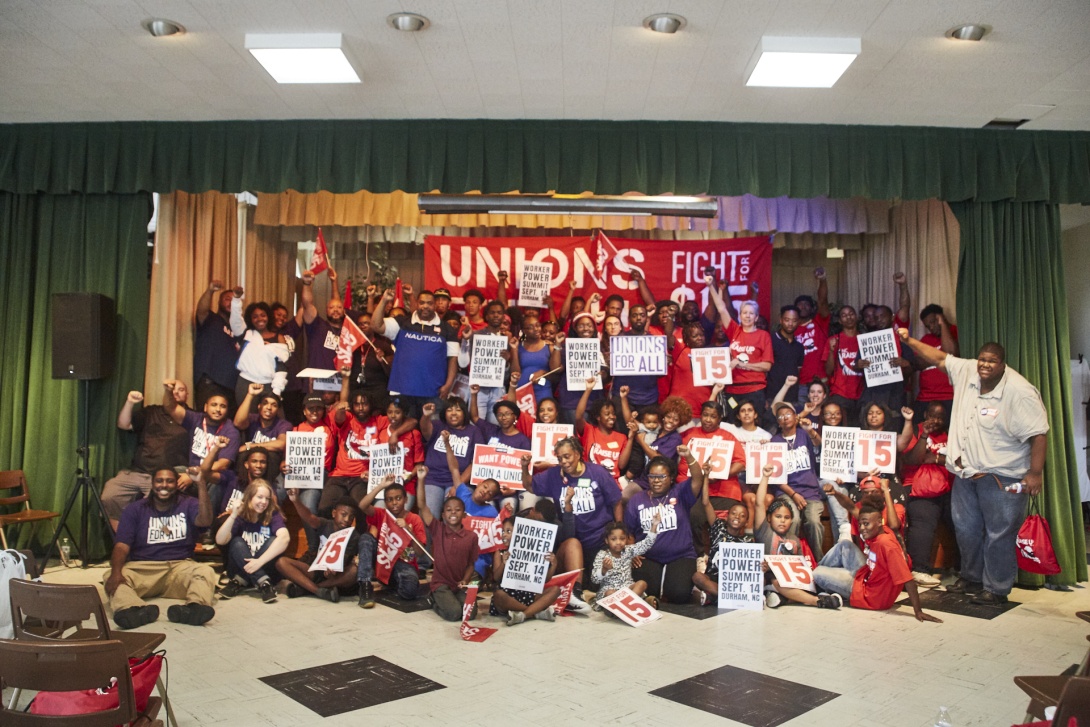

At the recent Worker Power Summit in Durham, North Carolina, over 120 low-wage workers came together to strategize how to continue to build power across the South. (Photo via NC Raise Up/Fight For $15.)

Over 120 low-wage workers convened in Durham, North Carolina, on Saturday, Sept. 14 for the Worker Power Summit hosted by NC Raise Up/Fight For $15. It billed itself as the first regional convening of low-wage workers from all sectors of the economy and came amid positive public perception of unions as well as growing interest in what's known as "sectoral bargaining"or "unions for all", an approach embraced in Europe and Australia in which workers organize by industry rather than company.

"I am here because we are trying to organize, so we can build these unions and make a better way of life and get out of low-wage working," attendee Wanda Coker told Facing South. Coker has been involved in the Fight For $15 movement for several years and led a session on unionization at the summit.

Among the speakers was Mary Be McMillan, president of the North Carolina AFL-CIO. She talked about how workers across the South are making meaningful change by protesting against low wages, sexual harassment, and unsafe working conditions. At the same time, she said, workers are forcing the nation to grapple with systemic racism and the connections between "poverty and mass incarceration, between wages and immigration reform, between justice in the workplace and justice in our schools, our courts, and our country."

While systemic change is needed, she said, it won't come from Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, or any other person vying to be the next president of the United States: It will come through "uniting and building a bigger, bolder labor movement."

As they do in the broader grassroots Southern labor movement, Black women like Eshawney Gaston played a key role in the summit. In her speech at the summit, Gaston — who joined the Fight For $15 two years ago while working a low wage job in Durham — noted that Black women are disproportionately impacted by low wages and emphasized the importance of fighting not just for raises but for union rights. "When we organize ourselves into a union," she said, "that's the way we shift the balance of power for workers in Durham and across the country."

The summit offered strategic discussions, team-building activities, and sharing of successful organizing tactics. In a session on wage exploitation, participants discussed the fact that McDonalds President and CEO Steve Easterbrook makes over $7,000 an hour while none of them make that much in a month. Because of these startling pay disparities, it's increasingly hard for low-wage workers to survive. In North Carolina alone, there are 1.47 million poor or low-income people, disproportionately children and people of color, and in some places in the state minimum-wage earners must work 87 hours per week just to afford a basic two-bedroom apartment.

Though the numbers might seem hopeless, long-time activist Bertha Bradley urged fellow workers to keep going. "We're not asking you to quit," she said. "We're asking you to fight."

As a regional gathering, the summit also addressed the particular conditions the movement faces in the South, which has the nation's highest rates of poverty, child poverty, and uninsured people and the lowest rates of economic mobility, union membership, and LGBTQ nondiscrimination laws. The participants made it clear that they don't think it's any accident that the country's poorest region is also one where states have historically made it difficult to unionize and collectively bargain. Some participants even reported that people of different races are kept separate at work, which they suspect may be done to dissuade organizing across racial lines.

The summit drew many veteran leaders in the Fight For $15 movement — people like Terrence Wise of St. Louis, who serves on the national organizing committee. Wise emphasized the power of organizing in the South. "In places where racism, wages, and working conditions are lowest, like they are in the South," he said, "when those workers organize, fight and win, it raises up everyone in America."

The summit also drew people new to the movement. They included local Walmart worker KiComa Quinn, who said she felt alone before but now sees herself as part of a movement of low-wage workers that has expanded to 230 cities, 33 countries, and six continents. She also said the summit changed the way she thinks about her power as a worker. "I do have rights that I didn't know about," she said.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.