VOICES OF RESISTANCE: Poetry as a portal to social change

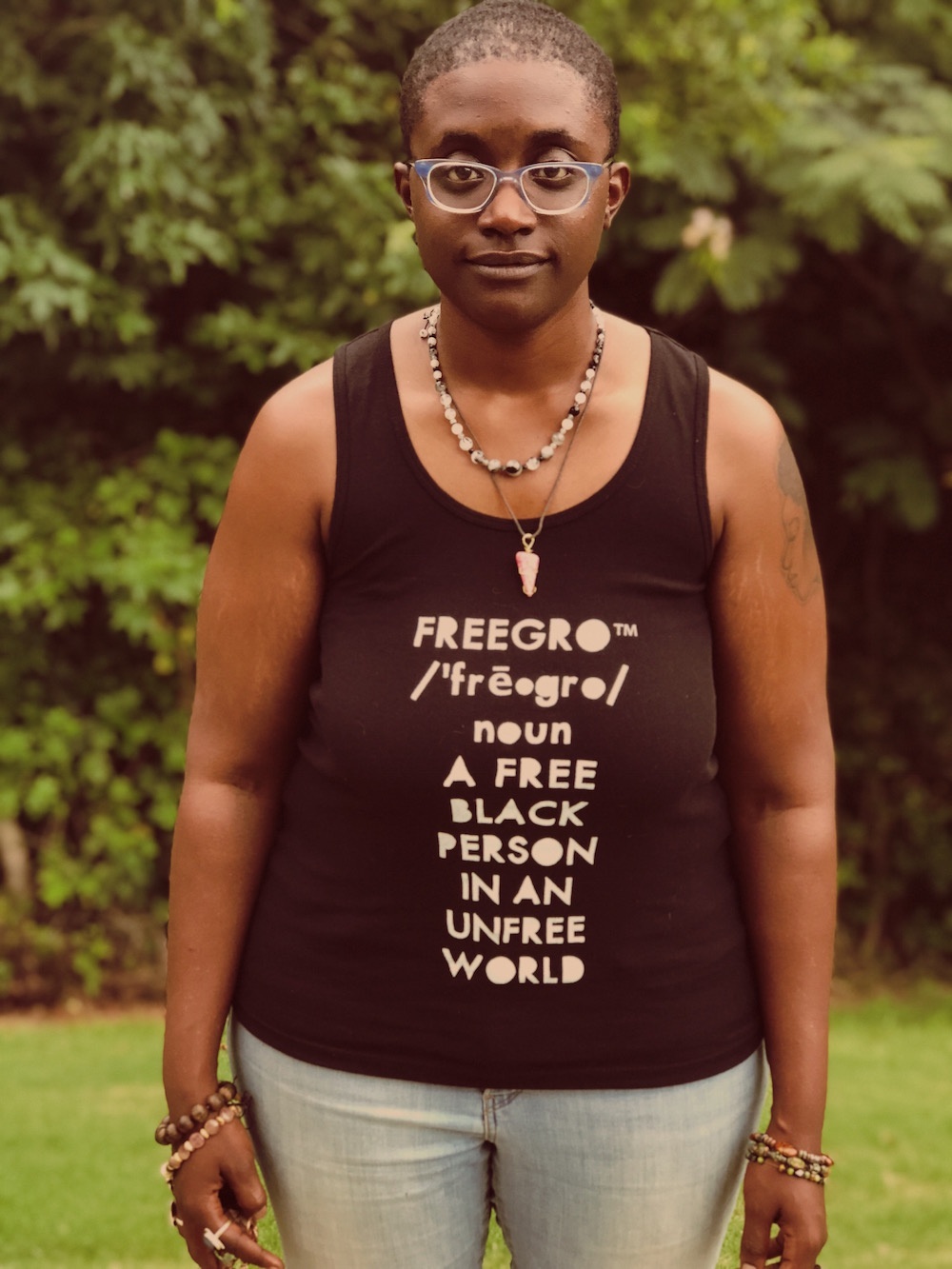

Marlanda Dekine is the co-founder of Speaking Down Barriers, which uses poetry as a portal to transformative dialogues. (Photo courtesy of Marlanda Dekine.)

Poetry has a deep history in the civil rights movement. It has been used to shed light on injustices, and it has also been used to bring people together to create change. In Spartanburg, South Carolina, trained social worker and spoken-word artist Marlanda Dekine — whose pen name is Sapient Soul — seeks to do just that.

Through her work as an advocate and therapist for abused children and through other experiences, Dekine — who is African-American and not a Spatanburg native — saw firsthand that her new community was very polarized along the lines of race and class. She also realized that there was fear about openly speaking to the big issues facing it: racism, classism, and other inequalities. Seeking to bridge the divides, Dekine and her colleague Scott Neely, who is white, cofounded Speaking Down Barriers, a nonprofit that uses poetry to spark transformative dialogues.

Speaking Down Barriers describes itself as "a team of listeners, healers, artists, researchers, teachers, theologians, and creatives who work together to offer encounters that transform our life together across human difference." The group began in 2013 as a monthly conversation on racism that drew about 20 people, and it has since grown to as many as 100 participants.

We recently spoke with Dekine by phone about her work for our ongoing "Voices of Resistance" series, which aims to draw insight and inspiration from the South's deep history of struggle for social change and to learn from a new generation of Southern leaders working in today's volatile political climate. Her responses have been lightly edited for clarity. If you have ideas for other Southern change makers to feature in the series, please contact Rebekah Barber at rebekah@southernstudies.org.

Tell me about your background and what led you into activism.

I am a licensed social worker and a poet. My work as a poet is performing and speaking, and my work as a social worker is seeing the ills of the world. I come out of the training of social work, but my poetry speaks to my life experience.

Tell me about why you decide to found Speaking Down Barriers.

Our work began with a poem. I was sharing a poem at a conference, and Scott Neely, my colleague who would eventually co-found Speaking Down Barriers with me, pulled me aside and asked if we would share poetry at his church.

I was a part of a Black group of poets, and this is a white guy in a suit … very strait-laced. At the end of our conversation he said, "I really think that should be in the chapel at my church." We sat down for coffee several times, swapping stories about life. When we found ourselves in the chapel, we were talking about classism within Spartanburg. That was the first dialogue we had. I think it was founded because we could see just in our talking alone how large the gaps were, even in our attempt to work together and to build something.

We weren't sure what we were jumping into at the time. It was just poets organizing through the church and getting the community to come out and talk. But what we found was that people wanted to talk about the really hard stuff, and it just tended to not go so well whenever forums were held.

I'm not from Spartanburg, and so I was the person who would ask questions that maybe I wasn't supposed to ask, or maybe that wouldn't have been the normal way of doing things. I would say, "Are we concerned about this being gentrification?" I noticed very quickly that people would literally begin to whisper. And these were community leaders I was meeting with. When I would bring up the disparities that I see, or the abuse of Black and Brown students in schools that I saw when I worked as a therapist for abused children, everything was literally hush, hush, hush.

When that space opened up, we found that there were many people who were ready for a place to speak. There were also people who may not have been ready to speak but were ready to listen. And so then you have people disagreeing in open space and not falling apart. This agreement made a fuller picture of everyone in the room. It was like when James Baldwin talks about it being books that taught him about all the pain in the world. The space opened up that shared story and forced us to acknowledge it as a shared story.

So you found that people were more receptive to having difficult conversations when engaging through poetry or other creative ways of communicating?

Yeah, definitely. We use spoken poetry in every dialogue for that reason. There was a period of time when we let the poetry go a little because we were thinking that we weren't doing quote, unquote, "activism" right. We got some criticism and we took it seriously, because the last thing that we wanted to do was to be out here making light of things that have been painful. For some folks that was the perception they had, so we listened to that. But we found that the dialogue began to fall flat. They were still dialogues, they were still getting some work done inside of people, but it was a flat room.

I think that's what art does — it bursts a hole that we can all walk through like a portal.

When we brought the poetry back into the room, it was as if you plugged something into an electric socket. There's something about a poet speaking from their experience. We even have visual artists who share their art sometimes. There's something about that piece of creation grounding the room; it almost serves as a place that everyone can touch and grab. And then we're all together, we're standing at attention even though we don't know we are. And with that intention, we're moving forward into a space of visioning, into a space of confrontation, into a space of progress. Without art, I don't know if that space would be able to go as deep as it goes. It really goes deep.

Art and poetry have historically been a key part of social movements. Can you talk about some of the people you are inspired by?

Well, I mentioned one: James Baldwin. Other than than James Baldwin, Audre Lorde. We say that she is the mother of our work, mainly because her writings and speeches have a lot to do with intersectionality and working very intentionally across very difficult differences and not acting like they don't exist.

Nina Simone is another influence. She was so misunderstood and went through so much. She kind of found herself within herself, but at the same time there was so much beauty, majesty, and poise to her. There was a willingness to go on tour and see lynchings and say, "Now my songs must be around this. Now my songs must bring awareness around this." Amiri Baraka is also an influence. I think that there is a lot of woundedness I can relate to. I still get sad for Amiri Baraka when I read his writings, but he is still very influential to me. Lucille Clifton is another influence.

For some reason, my mind is going to straight to Harlem. It's going straight to that period of time where there was so much being created and so much difference. I think about Langston Hughes having a disagreement with Zora Neale Hurston around language: Should we use more polished language? Or should we talk how we talk ? Or should we include our dialect? I think about how they were able to have that difference and still create such beautiful art that moves us and moves us forward. I think that's what art does — it bursts a hole that we can all walk through like a portal.

You mentioned Audre Lorde and intersectionality. Can you talk about ways that, particularly as a Black woman, you have been able to teach intersectionality, and how certain groups are impacted in a particular way because of their identities?

Yes. So in my book, a good bit of it is about my own identity, about navigating my identity, and then confronting white supremacy. There are kind of two sides to it, so the book is called "i am from a punch & a kiss." I say punch and a kiss, speaking of my own personal life and also of what it is like to live in this country.

And so what are the things that happen to us, and what is the beauty that we create anyway, or that comes out of it? Because I'm coming from a Black, Queer, woman space, I know my poetry tends to open up things that people have not considered because they're not in that space and identity. And so, in teaching intersectionality, we're very focused on individual stories and having people to listen to the points of difference, the points of discomfort in their bodies, because sometimes when we hear something that's so different from us we can feel the difference. We don't know what it is we're feeling, but we're feeling it. Maybe it's fear.

And so, we really engage it like a practice. We stop the room and say, "Look around. Right now there are various races in this room, there are various genders in this room, there are various sexual orientations in this room, and I want you to think about how often you sit down in a room like this and have this kind of conversation, and why it's not so often."

Every dialogue, we're pulling out our differences because our collective struggle comes from those differences.

Recently a woman said, "I just think that if we sit down long enough, we'll realize that we're more the same than we are different." And one of the facilitators said, "Yes, we will find points of sameness, but it doesn't erase the points of difference, and why is it hard to sit with our points of difference?" Then that's when people began to say "because it's scary," "because I think that your difference may get you killed," or "people accuse me of a privilege I don't understand." And when all of that comes out in the room, it's hard to not fall immediately into teaching what intersectionality is, and how we are all carrying levels of privilege, levels of oppression. We talk about it as a web that we're kind of walking through and trying to get out of.

You were able to bring this model of healing through the poetry and the arts to other states. Can you talk about that?

Yes. We have the Speaking Down Barriers Squad National Network. We go to another community and spend a week there. The first three days we do listening sessions with a cross-section of the community. And it really is a cross-section. It takes them a good amount of time to get a really good group of people because they'll bring us a list and explain who's who, and we'll say, "Nope, we need a better cross-section."

We interview about 25 folks and try to get a good handle on the community that we're in. After having talked to the folks that brought us in, we facilitate a dialogue and train a team to facilitate ongoing dialogues. It's not that the group we work with becomes Speaking Down Barriers, but it really is a collaboration. We push them to collaborate.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.