Honoring Reconstruction's legacy: Educating the South's children

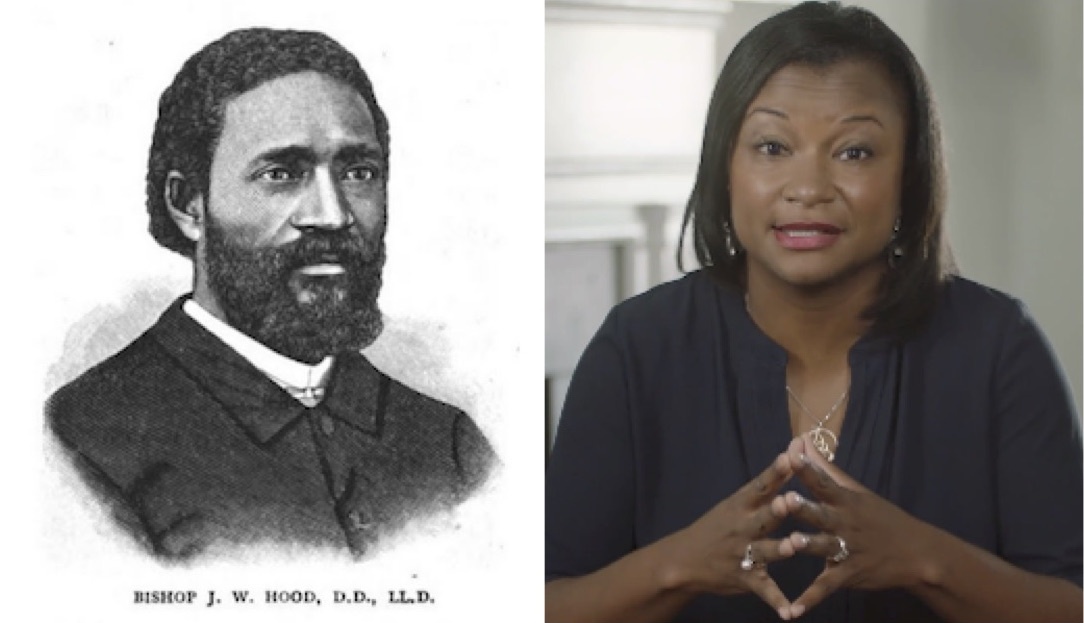

Bishop James W. Hood (at left) is one of the Black political leaders who helped write North Carolina's progressive 1868 state constitution that created the right to a free public education for all; he then served as a leader of the state's new school system. This year, as part of a wave of educators running for public office, former elementary school principal Aimy Steele (at right) is seeking a seat in the North Carolina legislature as an advocate for more education funding. Steele's husband, Michael Steele, is a pastor who attended Hood Theological Seminary, which is named after Bishop Hood.

"There is one sin that slavery committed against me, which I can never forgive. It robbed me of my education; the injury is irreparable."

These words, attributed to James Pennington, a formerly enslaved man and Yale University's first Black student, captured the intense desire of newly-freed Black people to be educated. Though slavery had deprived them of the freedom to read, to write, to learn, emancipated Black men helped draft new constitutions after the Civil War that for the first time gave the right to free public education to all of the South's children — black and white, rich and poor. Before the Civil War, the only Southerners who got an education were those whose families could pay for it themselves.

Mississippi's 1868 constitution, for example, required the state to encourage "intellectual, scientific, moral and agricultural improvement, by establishing a uniform system of free public schools." Florida's constitution drafted that same year said it was the state's "paramount duty … to make ample provision for the education of all the children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference."

To fund the South's first free, statewide public school systems, the Reconstruction constitutions earmarked certain taxes for public education. Black and white students took advantage of the new opportunity to obtain education that was previously accessible only to the wealthy few. By 1875, half the children in Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina were enrolled in school, according to historian Eric Foner's "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution."

During Reconstruction, racially segregated schools were not mandated by state law. In fact, constitutions in two states — Louisiana and South Carolina — explicitly prohibited them. It was only later during the Jim Crow era, with its white-supremacist governments, that racial segregation in schools and other institutions became the law of the land in the South.

The Reconstruction school superintendents viewed education as "the foundation of a new, egalitarian social order," as Foner said. They included men like Bishop James Walker Hood, a Black man born free in Pennsylvania who came to North Carolina as a preacher during the Civil War and became a political leader and groundbreaking integrationist. Hood helped draft that state's 1868 constitution and was appointed assistant superintendent of public instruction shortly after. In just a few years, he oversaw the education of nearly 50,000 Black children, and created a department dedicated to educating the deaf and blind.

Indeed, during Reconstruction, those who had been discarded by Southern society — Blacks, the poor, people with disabilities — gained access to an education and other basic rights they never had before. And by the 1890s, North Carolina's progressive, multiracial "Fusion" government, which had made funding for public education a priority, controlled the state legislature, the governorship, and both U.S. Senate seats.

Separate and unequal

But as North Carolina historian Timothy B. Tyson observed in a 2013 essay, "For some whites, Black citizenship itself — let alone raising taxes to educate the poor — justified any level of resistance."

Just 30 years after adopting the progressive 1868 Reconstruction constitution, North Carolina was the site of a deadly white-supremacist coup d'état: the Wilmington Massacre of 1898. Days after the state's then-largest city elected a white Fusionist mayor and multiracial city council, vengeful whites stormed through the city, killing as many as 300 Black people and terrorizing countless others into fleeing town.

The coup and statewide campaign of voter intimidation that followed paved the way for white-supremacist Democrat Charles B. Aycock to win the 1900 governor's election. Aycock — who advocated for a constitutional amendment that would disenfranchise Blacks — would come to be known as "the education governor." Under his leadership, teachers' salaries increased, and hundreds of new schools were built. Yet the new schools for Black students were underfunded, and Black and white teachers were not paid equally.

But even as their civil rights were being stripped away under Jim Crow, Black people took action to ensure their children were educated. In 1902, for example, Charlotte Hawkins Brown became the first Black woman to found a school for African Americans in North Carolina: the Palmer Memorial Institute in Guilford County. A private school, Palmer was one of the few to offer college preparatory instruction — and the rare one to teach African-American history. And across the South, historically Black colleges and universities established after the Civil War trained future civil rights leaders, legal scholars, and others who would ultimately help dismantle segregation.

Young students also took on the fight for equal education. In 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns led 450 of her fellow students in a walkout to protest the overcrowded and dilapidated conditions of their segregated high school in Farmville, Virginia. One of the first civil rights protests of its kind, the walkout drew the attention of NAACP lawyers, who filed a federal lawsuit that was one of five combined into the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case that ultimately ended legal segregation in the U.S.

By the time NAACP chief counsel and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall took on the Brown case in 1951, the NAACP had for decades been developing a strategy to challenge segregation. Handing down its decision in the case in 1954, the high court unanimously ruled that "separate public schools are inherently unequal."

Southern states vigorously defied the Court after Brown. Some white parents sent their children to private schools — so-called "segregation academies" — where they wouldn't have to learn alongside Black children. Other whites engaged in more violent measures to exclude Black children, such as the 1958 bombing of a public high school following years of mounting racial tension in eastern Tennessee.

A decade after Brown, just 2.3 percent of the nearly 3 million school-aged Black children living in the former Confederate states attended racially integrated schools, as investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones reported for The Atlantic. It wasn't until 1960 that 5-year-old Ruby Bridges of New Orleans became the first Black child to attend an otherwise all-white public elementary school in the South. But then in 1968, the Supreme Court ordered states to eliminate segregation "root and branch." By the 1970s, 90 percent of Black children in the South attended integrated schools, making the South's schools the most integrated in the country.

Then came the Reagan era. As Hannah-Jones noted in a 2016 story for the New York Times Magazine:

When Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, he promoted the notion that using race to integrate schools was just as bad as using race to segregate them. He urged the nation to focus on improving segregated schools by holding them to strict standards, a tacit return to the "separate but equal" doctrine that was roundly rejected in Brown. … Reagan eliminated federal dollars earmarked to help desegregation and pushed to end hundreds of school-desegregation court orders

In a lecture this month at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, Jones warned that Southern schools today are more racially segregated than they've been in decades. Research has shown that resegregation can have a dramatic effect on the quality of education students receive, because white students generally receive more education funding.

"Today we have schools that look like Brown never happened," Hannah-Jones said.

Enforcing education mandates

In recent decades, state courts in the South and around the country have ruled that legislatures are violating their constitutional duty to fund an adequate or "uniform" education for all children. Education lawyers shifted their focus to state courts after the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973 rejected an argument from Texas school districts that the federal Constitution protects a right to an equal education.

Some of the same Texas school districts that lost at the U.S. Supreme Court sued the state in the mid-1980s in state court. Most of the subsequent rulings by state courts agreed that Texas' unequal school funding system violated its constitutional duty.

But state courts have had mixed results in getting legislatures to comply with their orders to provide more funding or more equitable funding. Some recent rulings have led to political backlash, with legislators responding by trying to pack the courts or supporting efforts to unseat elected justices. In Kansas, for example, state senators responded to state court rulings to require more school funding with a 2016 proposal to allow for the impeachment of justices who "usurp the power of the legislative or executive branch."

Many of the current education funding lawsuits arose out of budget cuts imposed after the Great Recession 10 years ago. After the Texas legislature slashed education funding by $5.4 billion in 2011, two-thirds of the state's school districts sued. The trial court ruled in favor of the school districts three times, but the Texas Supreme Court overturned the rulings in 2016.

The opinion by Justice Don Willett — recently appointed to a federal appeals court by President Trump — acknowledged that school funding was "undeniably imperfect, with immense room for improvement" but said that it still "satisfies minimum constitutional requirements."

"We decline to usurp legislative authority by issuing reform diktats from on high, supplanting lawmakers' policy wisdom with our own", the decision continued. The justices instead encouraged the legislature to impose "transformational, top-to-bottom reforms."

Many of these lawsuits have resulted in decades of litigation. For example, North Carolina's high court is now hearing a lawsuit originally filed more than 20 years ago arguing that the state is violating its constitutional mandate to offer a decent education to all students.

Taking action for better schools

Florida also faced a lawsuit over inequities in its school funding system that gave wealthier districts more money. After the state Supreme Court ruled in 1996 that the schools satisfied the minimum constitutional requirements, voters decided that those minimum requirements were not enough.

In 1998, Florida voters amended the state constitution's education clause to restore some of the language from the 1868 version, which said that educating children is the state's "paramount duty." The new amendment also required a "high quality education." In addition, voters approved amendments to require early childhood education and smaller class sizes from kindergarten through third grade.

In 2009, a coalition of schools and parents sued Florida under the new education clause. The state Court of Appeals threw out the lawsuit last year, arguing that the judiciary still lacks the authority to order specific reforms or more funding. The state Supreme Court is reviewing the case.

Elsewhere across the South, educators are not waiting for judges or legislators to act. Earlier this year, teachers in West Virginia ignited a nearly two-week long strike to protest low teacher pay and high health care costs. The strike — which ended when the state legislature agreed on a 5 percent pay raise for teachers and other state employees — inspired similar walkouts in Kentucky and North Carolina, where teachers advocated for better pay and more resources for students.

Inspired by these walkouts, an unprecedented number of teachers and other educators are running for seats in state legislatures this year — 550 nationwide, and over 50 in Kentucky alone. They are supported by the National Education Association (NEA), the country's largest professional union.

"Now, in the wake of historic walkouts and school actions, we have a chance to leave our mark and elect to office public education champions who will raise their voices and fight for our students and public education," said Lily Eskelsen Garcia, NEA president. "This is our time. This is our movement."

(Research assistance from Facing South intern Benjamin Barber. This is the third story in a series on the legacy of progressive Southern constitutions that were rewritten during Radical Reconstruction. To read the first, on the freedom to vote, click here.)

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.