Medicaid work requirements would worsen South's health care crisis

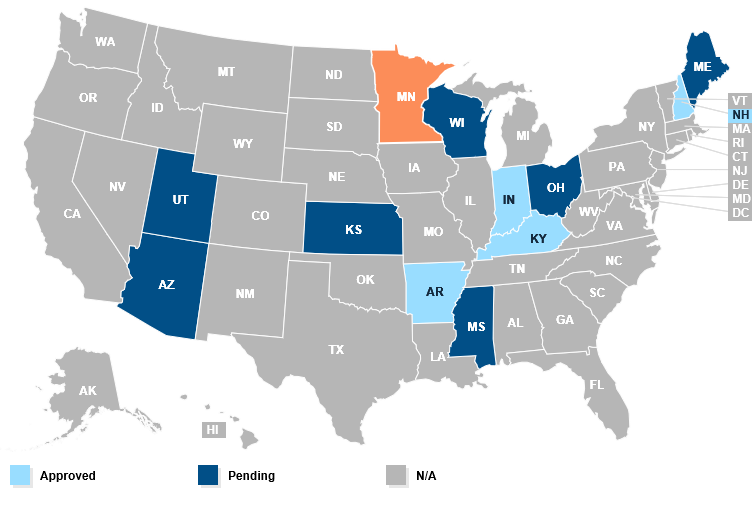

This Kaiser Family Foundation map shows the approved and pending state proposals to impose Medicaid work requirements, which would strip health care coverage from tens of thousands of people. For an interactive version of the map, click here.

"How many more babies? How many more children?"

Those are the questions Callie Greer tearfully asked earlier this month at the Washington, D.C., launch of the 40 Days of Action for the Poor People's Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, held the day after Mother's Day. Her own daughter, Venus, died of stage 4 breast cancer in Alabama because the state had refused to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and she could not get treatment until it was too late.

Every year, thousands of people like Venus die because they don't have insurance and thus lack access to health care. It's a problem people living in the South know too well. Because nine out of the 13 Southern states refused to expand Medicaid, the region is home to 90 percent of Americans who fall into the health care coverage gap — not wealthy enough to afford private insurance but not qualified for the public health insurance program for the poor and disabled.

Now the Trump administration wants to make it even more difficult for Americans to access Medicaid. In January, the administration sent a letter to state Medicaid directors calling for work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. Last month President Trump doubled down on his stance by issuing an executive order that aims to force citizens who do not meet certain work requirements off Medicaid, food assistance, and other safety-net programs.

Trump claims the policy would decrease poverty and provide work opportunities. But the majority of adult Medicaid beneficiaries are already working, though many are forced into part-time work by job-market limitations. And if they don't work, it is generally for good reason: because they have physical disabilities that leave them incapable of working, or are the caretakers of those with disabilities, or struggle with mental illnesses that limit their ability to work consistently, or are part of the homeless population that faces enormous barriers to obtaining employment.

Even though experts say Medicaid work requirements will create more problems than solutions, two Southern states — Arkansas and Kentucky — have already been granted federal approval to begin implementing them. These states, among the nation's poorest, expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, but the work requirements are expected to push thousands of residents into the coverage gap.

Arkansas's work requirement is set to take effect on June 1 and will apply only to the 280,000 state residents who received health insurance through Medicaid expansion. Under the policy, Medicaid enrollees will be required to meet an 80-hour monthly work requirement. If they are unable to meet the requirement for three months during the year, they will be locked out of Medicaid until the following year. And because the plan will require enrollees to report work hours through an online portal, some may lose coverage not because they failed to meet the work requirements but simply because they lack the internet access to prove it.

Kentucky's work requirement is set to take effect in July. But 15 residents have filed a class-action lawsuit to challenge the legality of the plan, which would require all Medicaid enrollees — not just those covered under the Medicaid expansion — to complete 80 monthly hours of employment, education, job skills training, or community service. If implemented, the plan is estimated to save the state over $2.4 billion because thousands will be kicked off the Medicaid rolls.

Kentucky's plan has raised questions about disproportionate racial impacts. The state will first impose the work requirement in northern Kentucky, which includes Jefferson County — the county with the largest Black population in the state. That means those most affected will be poor African Americans. But eight counties in rural southeastern Kentucky with high rates of unemployment — and where whites make up over 90 percent of the population — will be exempt from the work requirement. George Washington University health law professor Sara Rosenbaum called it "a version of racial redlining."

A recent analysis by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) found that even Medicaid recipients who regularly work could be at risk of losing coverage. That's because people working low-wage jobs are more likely to have irregular working hours or gaps in their employment. CBPP estimates that one in four people who work enough hours over the course of a year to satisfy Kentucky's work requirements could still have at least one month where they fall below the 80-hour monthly requirement and thus risk losing coverage.

Besides Arkansas and Kentucky, Indiana and New Hampshire have also had Medicaid work requirements approved by the Trump administration. Several other states have proposals pending, including Mississippi — which unlike Arkansas and Kentucky did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Thus a single parent in Mississippi can make no more than a meager $227 a month to qualify for Medicaid.

Earlier this month, Seema Verma, the administrator for the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, cautioned Medicaid non-expansion states against imposing work requirements over concerns about coverage loss, while a legal filing by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in the Kentucky lawsuit said the Trump administration views work requirements as an option only for adults in expansion states. If Mississippi's plan is approved, more than 20,000 Mississippians could lose their Medicaid, with women and African Americans most affected.

Meanwhile, Mississippi is not the only Southern non-expansion state considering Medicaid work requirements. Last month, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam announced plans to sign a work requirement bill that would cause an estimated 22,300 citizens to lose their insurance. And in North Carolina, Republican state lawmakers are currently negotiating ways to write a Medicaid work requirement program into the state budget now under consideration. If implemented, the policy would affect about 60,000 state residents. The federal government would have to approve the states' plans before they could take effect.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.