Trump's census move borrowed from racial gerrymandering playbook

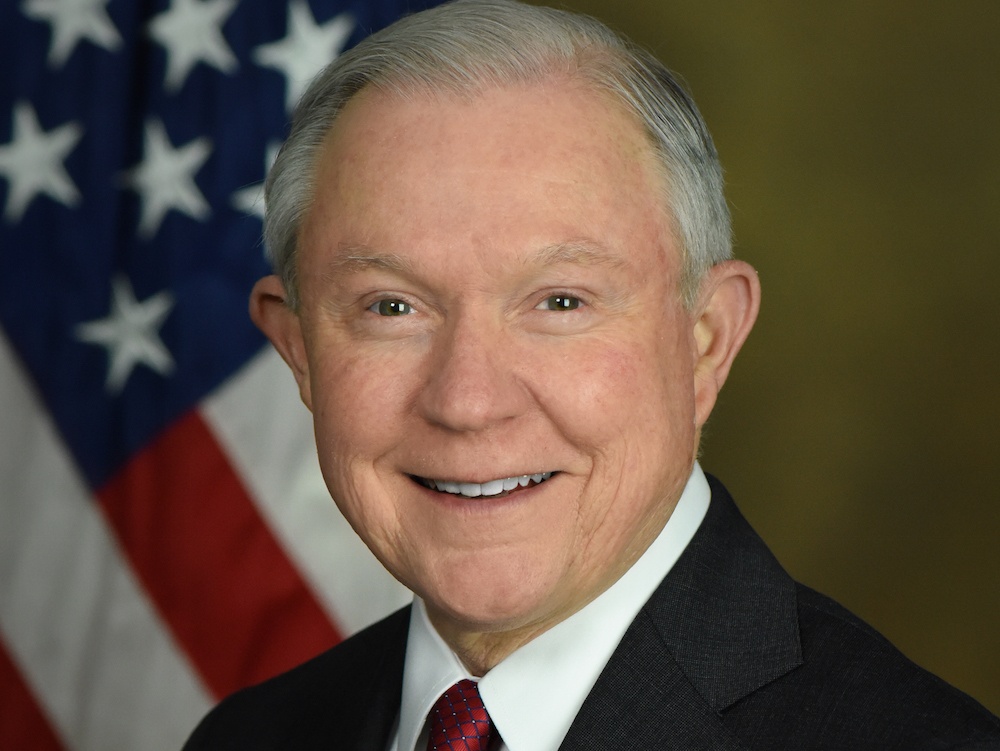

The Department of Justice, under the leadership of Attorney General Jeff Sessions, asked the Census Bureau to include a question about citizenship on the 2020 count, claiming it would help the DOJ enforce the Voting Rights Act. Legal experts question that claim. (U.S. Department of Justice photo.)

The Trump administration announced this week that the 2020 census would — for the first time in over 50 years — ask everyone in the U.S. whether they are a citizen. The announcement, which comes in the midst of the administration's immigration crackdown, has provoked new fears in the immigrant community.

Trump's Department of Justice (DOJ) requested the question in a letter, claiming that the citizenship information will help it better enforce the Voting Rights Act, which among other things requires states to ensure that voters of color are not robbed of the power to elect their candidates of choice through redistricting. The DOJ said it "needs a reliable calculation of the citizens voting age population in localities where voting rights violations are alleged or suspected."

DOJ's letter offered a hypothetical example: What if an election district had a majority of people of color, but lacked a majority of voters of color, due to the number of non-citizens? The letter claims that census citizenship data would be more accurate than the American Community Survey, a more frequent but narrower survey that has been used for VRA enforcement.

But voting rights advocates have pointed out that previous administrations did not need this data to enforce the VRA. Vanita Gupta, the former head of DOJ's Civil Rights Division who now heads the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, said the VRA justification was "plainly a ruse to collect that data and ultimately to sabotage the census."

University of Texas law professor Joseph Fishkin went even further, saying the administration "is lying." He argues that more precise citizenship data is not needed, because the question of whether voters of color can exercise political power in future elections is "necessarily approximate." Fishkin points out that no DOJ official had ever before requested a citizenship question on the census. Furthermore, the Obama administration protected voting rights across the South without asking for more detailed citizenship statistics.

While the new question will not help enforce the VRA, it could lead to less representation in Congress and state legislatures for people of color. Immigrant advocates and former Census Bureau officials have argued that many families with undocumented members would refuse to participate in the 2020 count because of the question. A September 2017 survey found that fears about the census have increased markedly among immigrants since Trump took office after campaigning against immigration, despite strict confidentiality rules implemented after World War II, when the Census Bureau gave government agencies information on Japanese Americans so that they could be sent to internment camps.

The decennial census already overcounts white people and undercounts people of color. The 2020 census could make that disparity worse, as neither the Trump administration nor the Republican-controlled Congress has not shown any interest in ensuring an accurate count. Earlier this year, for example, reports emerged that the administration was considering hiring University of Texas at Dallas political science professor Thomas Brunell — a discredited expert witness in gerrymandering trials and the author of a book titled "Redistricting and Representation: Why Competitive Elections Are Bad for America" — to run the census, though ultimately he withdrew from consideration. The bureau remains without a permanent leader.

Echoes of bogus gerrymandering claims

The administration's claim that its controversial census question would actually protect voters of color echoes a claim from Republican state legislators who racially gerrymandered black voters in Alabama, North Carolina, and other states under the guise of guarding their rights. But the U.S. Supreme Court has seen through GOP efforts to gerrymander black voters in the name of complying with the VRA.

When the VRA was passed in 1965, it required states and counties with a history of voting discrimination to "pre-clear" changes to voting laws or processes with the federal government. Although the U.S. Supreme Court struck down this requirement in 2013, legislators in Southern states still had to get the federal government's approval for the maps they drew following the 2010 census.

In North Carolina, legislators in 2011 sought to increase the percentage of black voters in two districts to greater than 50 percent. In his testimony during a racial gerrymandering lawsuit, former U.S. Rep. Mel Watt, an African-American Democrat who represented one of these districts for two decades, said that a legislator drafting the map had told him that his district had to be "majority-minority" to comply with the VRA. Watt laughed at the suggestion. "I'm getting 65 percent of the vote in a 40 percent black district," he said, adding that increasing that percentage is "not what the Voting Rights Act was designed to do."

Hired by the legislature to justify the gerrymanders, Brunell — Trump's now-abandoned Census Bureau pick — told the court there was "statistically significant racially polarized voting" in North Carolina that required "majority-minority" districts. The court rejected his conclusions, saying his report showed a "misunderstanding" of the VRA.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that decision, and in an opinion by conservative Justice Clarence Thomas struck down the racially gerrymandered map as unconstitutional. Thomas said the evidence showed "an announced racial target that … produced boundaries amplifying the divisions between blacks and whites." He said that legislators had downplayed the districts' "longtime pattern" of "crossover voting," in which enough whites voted for the minority population's candidates of choice for them to win.

Alabama made a similar defense of its racially gerrymandered map, but the U.S. Supreme Court also rejected its VRA excuse. Virginia's approach to redistricting was more like North Carolina's, but with a goal of at least 55 percent black voters for 12 state legislative districts. Brunell was also hired to help defend Virginia's maps but withdrew after another expert witness questioned his credibility. In the end, the Supreme Court upheld the use of the 55-percent threshold for just one Virginia district because legislators had determined that it was necessary to maintain the voting power of the district's black population, as the VRA requires.

Entrenching GOP power

Just as Republicans' use of the VRA to justify racial gerrymandering spurred lawsuits, so is their VRA excuse for the census citizenship question.

Several states have filed a lawsuit that argues the administration's decision to include the question violated a federal law that prohibits government agencies from taking "arbitrary and capricious" actions. The states — none of which are in the South — say that the question would not serve the administration's stated goal, "because an undercount of non-citizens and their citizen relatives will decrease the accuracy of census data" needed to enforce the VRA.

Legal reporter Mark Joseph Stern of Slate says the question could bolster the argument that Congress should represent only citizens and not "people" — an argument the Supreme Court unanimously rejected in 2016 in a case out of Texas. As Stern writes:

If the question survives a court challenge, it will fundamentally alter the composition of government, exacerbating overrepresentation in predominantly white regions while diminishing representation of immigrants and minorities. The question will tilt political power to the right in both Congress and state legislatures while depriving cities of vital funds for public health, schooling, and other social services. And it opens the door to a new kind of gerrymandering that will further suppress minority votes. The addition of this question may be Donald Trump's most lasting move as president, one with vast ramifications that will harm communities disfavored by the Republican Party through at least 2030.

This would be particularly true in the states with the most immigrants, including Florida and Texas.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.