Meet the organizer who helped create the soundtrack for the Poor People's Campaign

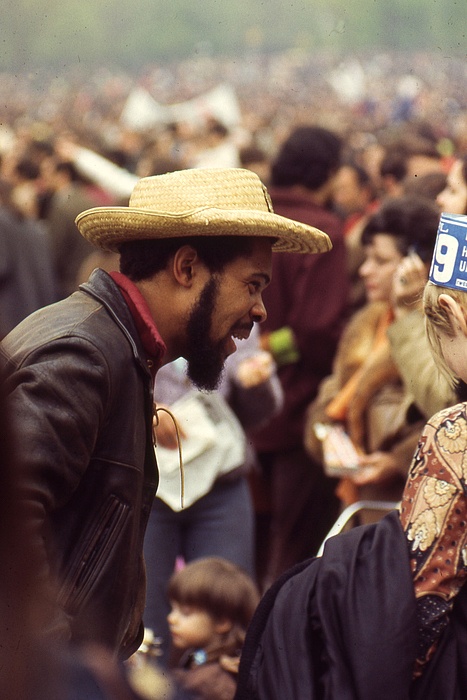

Jimmy Collier at the original Poor People's Campaign. (Photo by Erik Falkensteen used with permission.)

A recent conversation with a young organizer who is working for the Poor People's Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival prompted me to reconnect with Jimmy Collier. I wanted Jimmy — who was an organizer-musician with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) — to know that the songs he composed and recorded 50 years ago with the Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick continue to inspire activists for peace and equality.

In 1968, they recorded an album for Folkways Records titled "Everybody's Got a Right to Live" that served as the soundtrack for the original Poor People's Campaign — a mass mobilization of poor people who traveled to Washington, D.C., to engage in disruptive protests aimed at forcing government action to end poverty. The Poor People's Campaign was initiated by Martin Luther King Jr., who believed that President Lyndon B. Johnson had sacrificed federal War on Poverty programs for an expanded war in Vietnam. In the wake of King's assassination, organizers like Jimmy continued the work of the Poor People's Campaign, recruiting poor people from across the country to take part in the D.C. protests. Gordon Mantler's outstanding 2013 book "Power to the Poor" provides the best critical history of the Poor People's Campaign.

Beyond an occasional Facebook message, I had not spoken to Jimmy for at least 10 years. Knowing that he had suffered some recent health setbacks, I was glad to find him in excellent spirits. He was pleased to learn that young activists find meaning in his music. And he had been tracking the new Poor People's Campaign from his home in Fresno, California, where he and his wife, Cathy, moved a few years ago from their home near Yosemite National Park in order to be closer to their children. We updated one another regarding the whereabouts of mutual friends, many of whom were affiliated with the Western Workers Labor Heritage Festival — a yearly celebration of labor culture that brings together musicians, visual artists, poets, storytellers, and filmmakers. We first met at the San Francisco Bay-area festival in the mid-1990s, when Jimmy, playing guitar or banjo, shared billing with protest-song luminaries like Utah Phillips and Pete Seeger.

Following our phone conversation, I revisited a 1999 interview that I conducted with Jimmy along with Tenisha Armstrong, my longtime co-worker at the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University (now the MLK Research and Education Institute). In that interview Jimmy had discussed his musical upbringing in Fort Smith, Arkansas, his introduction to the movement as a community college student in Chicago, and his four-year association with the SCLC. Both the phone call and the interview reminded me of Jimmy's great qualities as an organizer and a friend. The conversation also reinforced ideas I have been thinking about with regards to our present political moment and the importance of movement building.

Within SCLC, Jimmy wanted to be recognized as an organizer, but SCLC leaders viewed him firstly as a musician. Jimmy was often tasked with warming up crowds as a song leader until the arrival of Dr. King or another featured speaker. "I got very clever at being able to get people going," he recalled. "As soon as he walked in, then pretty much I was forgotten. I mean it was kind of in an instant." SCLC leaders preferred Jimmy as an opening act over church choirs or high profile performers because he would leave the stage quickly and without fuss upon Dr. King's arrival. "It didn't bother me," he said. "It was sort of part of my job."

The lines between musician and organizer were always porous in the movement, so Jimmy made the most of his opportunities to organize. Assigned to work in Chicago under the direction of SCLC strategist James Bevel, Jimmy's talent for fusing topical folk songs with contemporary soul hits proved useful in organizing young African Americans who were skeptical of King and SCLC's advocacy of nonviolence. We were "trying to get the gangs on our side, or at least to get them to let us have nonviolent demonstrations," he said. "At least if they're not going to join, [they should] at least not stop" the protests. By the mid-1960s, freedom songs emerging from the Southern struggle sounded dated to Northern ears, but reworked hits by the Impressions and Sam Cooke resonated with Chicago's West Side youth. Jimmy's "Burn Baby Burn" — a dark lament and angry meditation on the urban rebellions of the mid-1960s written from the perspective of an arsonist — represent a creative peak of his efforts to merge soul and protest music. The song's subtleties, however, may not have translated well to SCLC mass meetings. Jimmy recalled that Dr. King suggested he not play "Burn Baby Burn" because of its tone.

At several points in our conversation, Tenisha and I raised criticisms of SCLC's strategy and tactics, echoing arguments we had read in scholarly accounts of the movement. Jimmy's gentle rejoinders reminded us that successful movements require flexibility and humility. "No one has the key to the timing, the evolution, or any of it," he said. "I mean, all you can do is what you can do at the time, and then if it's the right time things will jell, personalities will come together, energies will be created." Given the level of resistance, "it was a miracle that any of it ever worked," he added. Did we underestimate going into Selma, Albany, or Mississippi? he asked rhetorically. Ending Jim Crow segregation "was a goal that any rational person would have said was impossible to meet at any time, but that just wasn't going to stop it."

Though sympathetic to the criticisms of the movement's over-reliance on King's charismatic leadership at the expense of bottom-up organizing, Jimmy continues to admire SCLC's ability to forge powerful coalitions and to tie the local work to concrete legislative reforms. "My guess is you needed both" approaches, he said. "The situation was severe enough to where you need every style." Moreover, on the ground and in the face of sometimes deadly opposition, the fine distinctions tend to diminish in importance.

At 73, Jimmy may not be able to join us for the new Poor People's Campaign — traveling with his guitar can be a challenge these days and he is slowly recovering after losing his voice last year. But new organizers and artists will emerge to carry through on what is shaping up as a national campaign to confront poverty, racism, environmental degradation, militarism, and our debased political culture. The best of those organizer-leaders will engage the movement with at least a bit of Jimmy Collier's compassion, creativity, and generosity.

Tags

Kerry Taylor

Kerry Taylor is a board member of the Institute for Southern Studies, the nonprofit that publishes Facing South, and directs the Charleston Oral History Program at the Citadel: The Military College of South Carolina.