Behind the push to limit lawsuits by injured workers and consumers

Voters in two Southern states will weigh in this year on changes to state constitutions that would make it harder for injured people to find justice in civil court.

In Arkansas, a proposed constitutional amendment is on the ballot in November that would give the legislature the power to limit "non-economic" damages, such as pain and suffering, that juries can award. The bill proposing the amendment was sponsored by Sen. Missy Irvin and Rep. Bob Ballinger, both Republicans, and supported by corporate interests. Irvin works at her physician husband's medical clinic, while Ballinger is the former chair of his local Chamber of Commerce.

Proponents claim the so-called "tort reform" amendment would curb costs generated by what they call "frivolous lawsuits." However, damage limits by definition affect only those lawsuits with the worst injuries, where damages exceed a certain threshold. And limits on non-economic damages have a disproportionate impact on groups that generally have less income, such as children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Not surprisingly, the amendment is opposed by trial lawyers, who represent injured people in court. But it also faces opposition from a Christian conservative group, Family Council, which argues that it "allows the powerful to hurt … the least of these." And Mike Ross of Protect Arkansas Families, a group dedicated to defeating the amendment, criticized it for allowing limits on punitive damages, which are intended to deter deep-pocketed corporations that can easily afford ordinary lawsuit verdicts.

"You've got to inflict pain every now and then," said Ross. "And for many of these people, inflicting pain is hitting them in their pocketbook."

As the Arkansas Blog has reported, the state's nursing home industry bankrolled an earlier version of the proposed amendment, which would have capped non-economic damages at $250,000. The new version allows the legislature to set the cap at $500,000. Non-economic damages are particularly important in cases involving nursing home patients, who usually lack economic damages like lost income.

Michael Morton, who owns 15 percent of the nursing homes in Arkansas, has spent big to push the amendment and to elect sympathetic judges. One of these judges, Michael Maggio, is in federal prison after pleading guilty to bribery. Judge Maggio accepted a campaign contribution in exchange for lowering a $5 million verdict against Morton's company in a wrongful death lawsuit, which was filed by the family of a patient who died after a doctor's recommendation that she be hospitalized was faxed to a machine in the nursing home's closet.

After the Arkansas Supreme Court struck down some tort reform laws as unconstitutional in 2011 and 2012, Morton and other corporate interests began donating to the campaigns of their preferred judges. A similar pattern unfolded in other states in the 1990s and 2000s: Rulings to strike down tort reform laws were followed by an influx of corporate money into judicial races.

In Kentucky, state lawmakers and the Chamber of Commerce are pushing a constitutional amendment to give the legislature the power to limit damages in lawsuits. Sen. Ralph Alvarado (R), a physician, said the amendment is a top priority for the Senate, but it must have support from a super-majority in both chambers of the GOP-controlled legislature. The Kentucky Constitution now denies the legislature the "power to limit the amount to be recovered for injuries resulting in death, or for injuries to persons or property." The Kentucky Supreme Court has struck down tort reform measures in the past.

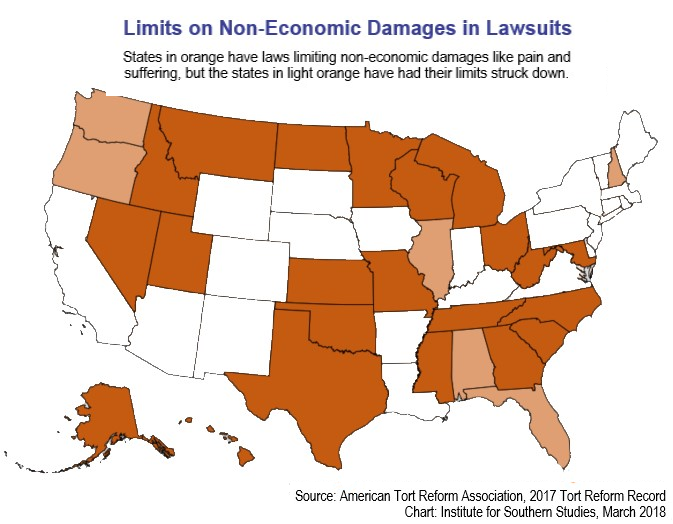

If Arkansas and Kentucky impose damage caps, every Southern state except Louisiana and Virginia would have statutes limiting how much juries can award for damages like pain and suffering. Many states also limit jury verdicts for medical malpractice.

A brief history of tort reform

The tort reform movement was launched in the 1980s by tobacco company Philip Morris and gained support over the years from the pharmaceutical, insurance, and health care industries.

After large class-action lawsuits against dangerous products like cigarettes and defective drugs, corporations that did not want to be sued launched "astro-turf" campaigns in Texas and other states to limit such lawsuits. A 1986 memo drafted by the Tobacco Institute laid out the plan to conceal the industry's backing of the groups: "In order to be totally effective," it said, "the grassroots effort must appear to be spontaneous rather than a coordinated effort."

Corporate-funded tort reform advocates engaged in a successful campaign to convince the news media and the public that companies faced an epidemic of frivolous lawsuits. As part of this effort, the facts of the notorious "hot coffee" lawsuit against McDonald's were distorted to downplay the company's role in ignoring previous burns and to misrepresent the victim's actions. The campaign stoked fears that justified new limits on lawsuits in states across the country.

Alabama and Texas led the way towards tort reform in the 1980s and 1990s. To remove constitutional obstacles, many of the same corporate interests that pushed the concept backed an effort by political operative Karl Rove to elect Republican justices to the Alabama and Texas supreme courts. Rove and then-Gov. George W. Bush subsequently turned Texas into a test case for draconian tort reform laws, making it nearly impossible to file a medical malpractice claim.

The conservative Texas Supreme Court has interpreted medical malpractice to cover nearly any lawsuit filed against a doctor — even one for sexual assault. A 2011 report from Texas Watch found that the Texas Supreme Court, elected with campaign cash from corporations and corporate lawyers, overturned 74 percent of the pro-consumer jury verdicts that it reviewed.

Among the groups that have lobbied for tort reform and spent millions to elect sympathetic judges are the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, its state affiliates, and the American Tort Reform Association (ATRA), which has been funded by the Koch brothers' conservative political network since at least 2004. In turn, the ATRA and tobacco companies created fake grassroots groups that pressed for lawsuit limits in Florida, Texas, and other states. Today the Chamber and ATRA continue to lobby state legislatures to limit civil justice. For example, the ATRA is fighting a pending Georgia bill that would allow sexual abuse victims to sue their abusers.

In Arkansas, meanwhile, another pending bill would allow nursing homes and other corporations to include clauses in contracts with customers that would bar jury hearings for complaints of mistreatment, negligence and other damages. If the proposed Arkansas tort reform amendment passes, the same state legislature would be empowered to limit the damages that severely injured people can receive for their pain and suffering.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.