Paul Manafort's role in the Republicans' notorious 'Southern Strategy'

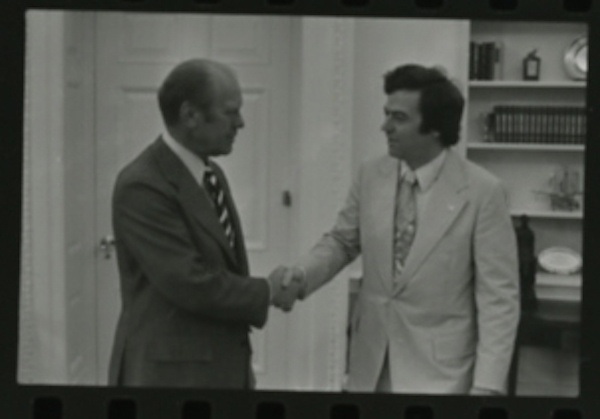

After getting his start in Republican presidential politics working for President Gerald Ford (left), former Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort (right) went on to work for the Reagan campaign where he deployed the so-called "Southern Strategy" of building white support for the GOP through dog-whistle appeals to racism against African Americans. (1976 White House photo via Wikipedia.)

As part of the ongoing probe into Russian efforts to help Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Special Counsel Robert Mueller this week handed down criminal indictments of three Trump campaign associates, among them former campaign chair Paul Manafort of Virginia.

In a 12-count indictment that also named his business partner, Manafort was charged with conspiracy to launder money, serving as an unregistered agent of a foreign power, making false statements and other crimes. The charges relate to his laundering through foreign shell companies millions of dollars made lobbying for a pro-Russia party in Ukraine — work he failed to properly disclose — and using it to buy luxury goods and property while avoiding taxes. Manafort surrendered to the FBI, pleaded not guilty and was placed under house arrest. If convicted, the 68-year-old faces up to 80 years in prison.

The charges against Manafort — a Connecticut native with business and law degrees from Georgetown University — cap off a controversial career in politics. Much of it he spent lobbying for notorious human rights abusers such as Angolan anti-communist rebel leader Jonas Savimbi and dictators Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, Mohammed Siad Barre of Somalia and Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

But before he was advocating for human rights abusers on the world stage, Manafort was helping the Republican Party gain advantage by embracing the politics of racism at home.

After launching his political career in 1976 as a delegate-hunt coordinator for the President Ford Committee, Manafort went on to co-found a political consulting firm. In that capacity he served as Southern coordinator for Ronald Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign, in which he exploited the GOP's "Southern Strategy" — an effort to build political support for the Republican Party among white Democratic voters in the South through dog-whistle appeals to racism against African Americans. It can be traced back to Republican Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential run and was used with great success by the Nixon campaign in 1968.

Two weeks after Reagan became his party's nominee at the 1980 Republican convention in Detroit, Manafort arranged to have him speak at Mississippi's Neshoba County Fair, a traditional forum for right-wing politics. The visit was hosted by Trent Lott, at the time a Mississippi congressman who would go on to serve in the U.S. Senate only to lose his leadership position in 2002 after praising the segregationist politics of former Dixiecrat-turned-Republican U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

The Neshoba County Fair takes place just seven miles from the county seat of Philadelphia, Mississippi. That's where during Freedom Summer of 1964 members of the Ku Klux Klan with help from the local sheriff and police murdered James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner, young civil rights workers who had been registering rural black residents to vote.

Mississippi declined to prosecute anyone involved in the killings at that time, so the federal government stepped in. After a lengthy battle, U.S. prosecutors finally managed to indict 18 people on federal charges of depriving the victims of their civil rights by murder. Held before an all-white jury and a white judge with a record of hostility to the civil rights movement, the trial resulted in convictions for seven men. None served more than six years in prison, so it's possible they attended the fair to hear Reagan speak.

In that historically and racially charged setting, what was the Reagan campaign's message to the overwhelmingly white crowd of 10,000? "States' rights" — the rallying cry for secessionists during the Civil War and for segregationists during the civil rights movement. Reagan said:

I believe in states' rights. I believe in people doing as much as they can for themselves at the community level and at the private level, and I believe we've distorted the balance of our government today by giving powers that were never intended in the Constitution to that federal establishment.

He went on to pledge to "restore to states and local governments the power that properly belongs to them." As Bob Herbert of the New York Times wrote years later in response to Republican efforts to cast Reagan's Neshoba County appearance in a more benign light, "Reagan may have been blessed with a Hollywood smile and an avuncular delivery, but he was elbow deep in the same old race-baiting Southern strategy of Goldwater and Nixon."

A more abstract racism

Reagan went on to win a landslide victory over incumbent Democratic President Jimmy Carter of Georgia and racked up a record hostile to civil rights.

He cut funding for the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. He sided with the Christian fundamentalist Bob Jones University in South Carolina in a case over whether institutions that discriminate on the basis of race can get federal funds. He even vetoed the Civil Rights Restoration Act requiring publicly funded institutions to comply with civil rights laws, though Congress overrode him.

The day after the 1984 general election, in which Reagan won a second term in an even more overwhelming landslide, Republican political consultant and White House political aide Lee Atwater of South Carolina became a senior partner in Manafort's consulting firm.

Atwater was known for his use of aggressive and racially charged tactics in his work with congressional campaigns, such as fake surveys implying an opponent was a member of the NAACP. In his work with Manafort's firm, Atwater masterminded the racially charged Willie Horton attack ads run by the George H. W. Bush campaign in 1988 accusing Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis of being weak on crime.

Atwater had discussed the origin and thinking behind the Southern Strategy in a 1981 interview with a political scientist. It surfaced in an audio recording obtained by The Nation magazine in 2012. In it he said:

You start out in 1954 by saying, "Nigger, nigger, nigger." By 1968 you can't say "nigger" — that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states' rights, and all that stuff, and you're getting so abstract. Now, you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites. … "We want to cut this," is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger."

Before he died in 1991, Atwater apologized for the tactics he used, noting that while he didn't invent negative politics he was "one of its most ardent practitioners." Manafort, though, has offered no apologies.

Making a monster

The racially divisive tactics pioneered by Manafort and his colleagues remain a feature of U.S. politics today, though they've been adapted to the times by exploiting white resentment toward Latinos and immigrants as well as African Americans.

After Manafort joined the Trump operation as chair in March 2016, political observers noticed a change in the campaign's tone. Trump stopped with the blatantly outrageous statements, such as saying protesters deserve to be punched in the face, and instead deployed new messaging about threats to "our way of life," and of crime and violence and the need for safety to "be restored."

And in a nod to history, the Manafort-led campaign had Donald Trump Jr. speak at the Neshoba County Fair that July. The crowd chanted, "Build that wall" while some waved Confederate flags. Asked before his speech about the controversy over the Mississippi state flag with its Confederate symbolism, Trump Jr. answered, "There's nothing wrong with some tradition."

But by August 2016, Manafort's work on behalf of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had begun drawing scrutiny in the U.S. press, which reported that Manafort may have illegally received millions of dollars in off-the-books payments from Yanukovych's party. Manafort resigned from the campaign on Aug. 19, 2016. But Republican leaders continued to praise his work for Trump.

"Nobody should underestimate how much Paul Manafort did to really help get this campaign to where it is right now," said political consultant Newt Gingrich, the former congressional leader from Georgia and GOP presidential candidate who served as an adviser for the Trump operation.

How did the Southern Strategy as refined by Manafort work for Trump? In the end, Southern states delivered 160 Electoral College votes to him — more than half of the 306 total that sent him to the White House. White voters favored Trump over Democrat Hillary Clinton by 21 points. Trump won among white men, white women, whites with and without college degrees, and whites of every voting age group.

One analysis found that had only white people voted in the election, Trump would have captured over 80 percent of all electoral votes — an outcome that Manafort and other Republicans helped engineer over the course of decades. As Jeet Heer observed in the New Republic, "The Southern Strategy was the original sin that made Donald Trump possible."

Manafort's trial is now tentatively set for April 2018. Regardless of what happens to him next, though, the political monsters he helped create live on.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.