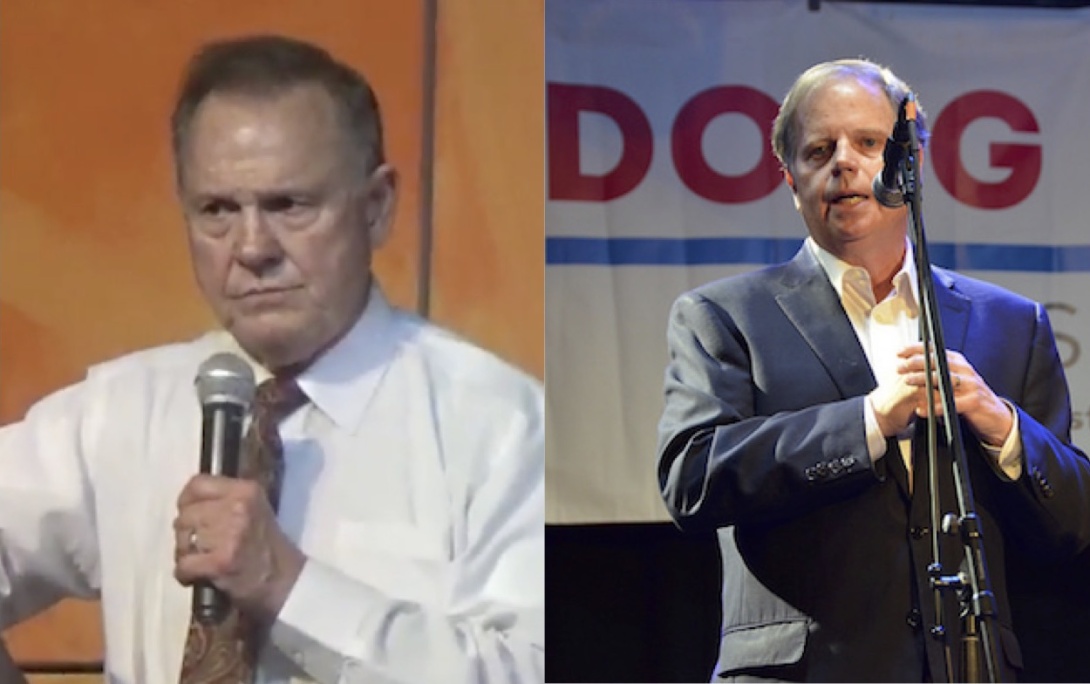

Voting restrictions could affect Alabama's special U.S. Senate election

Recent restrictions on voting adopted by Alabama could affect the outcome of the special election for one of the state's U.S. Senate seats pitting far-right Republican Roy Moore (left) against Democrat Doug Jones (right). (Photo of Moore by Rik Spoutnik via Wikipedia; photo of Jones via Open minded in Alabama via Flickr.)

Roy Moore's win in the Sept. 26 Republican primary runoff for Alabama's U.S. Senate seat previously occupied by Jeff Sessions has put an afterthought of a race back into the national spotlight. In a special election to be held on Dec. 12, Moore — a far-right former chief justice of the state Supreme Court who defeated the appointed incumbent Luther Strange — will face Democrat Doug Jones, a former U.S. attorney who successfully prosecuted KKK members for the 1963 Birmingham church bombing.

Alabama has taken a deep-red turn in recent years, with Donald Trump winning 62 percent of the vote last year. But Moore — who infamously refused to obey a federal court's order to remove a Ten Commandments monument he had placed in the lobby of the Alabama Judicial Building and was subsequently removed from office in 2003 — won his seat on the Alabama Supreme Court in 2012 with just 52 percent of the vote against a last-minute Democratic candidate, circuit court judge Bob Vance. An August 2017 poll found that Moore's unfavorability ratings among even Alabama Republican primary voters hovered around 33 percent, while another poll released this week showed Jones to be within 8 points of Moore.

The election has drawn national attention due to Moore's extremism, Trump's dwindling popularity, and Democrats' hopes for a wave in the 2018 midterms. In less than a week after Moore's victory, Jones had raised over $820,000 from all 50 states. And this week, former Vice President Joe Biden stumped for Jones in Birmingham, telling the crowd: "When he wins this race it'll send ripples down the country."

Given the fact that the contest is shaping up to be closer than many originally thought, and that turnout tends to be lower for special elections, the state's recent moves to restrict voting could make a critical difference in the outcome.

Alabama has long been an important battleground in the fight for voting rights. In 1965, it was the site of three Selma-to-Montgomery marches demanding voting rights for African Americans, which drew the eyes of the world when nonviolent protesters were met with violent police repression on a bridge named after a former Confederate general and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. Moved to action by the sacrifice of the protesters, President Lyndon B. Johnson successfully pushed Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which among other things required counties and states including Alabama that historically engaged in voter discrimination to get U.S. Justice Department preapproval before changing voting laws.

Almost half a century later, Alabama played an integral role in the gutting of the Voting Rights Act when Shelby County sued then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder to end the preapproval requirement. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in its landmark 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder struck down the law's preapproval provision. The 5-4 ruling freed states including Alabama to pursue voting rights restrictions that would not have survived preapproval.

And that they did. Of the 14 states with restrictive new voting laws in effect for the first time in last year's presidential election, six were previously covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act — including Alabama.

Here are some of the ways that Alabama has limited voting in recent years:

Voter ID law

In 2011, even before the Shelby decision, Alabama passed a law requiring photo ID to vote; the move came after Republicans took control of both chambers of the state's legislature for the first time since Reconstruction. Proponents said such a law was necessary to protect against voter fraud. However, a recent study found that between 2000 and 2014 there were only 31 credible allegations of voter impersonation — the only type of fraud that photo IDs can prevent — out of over a billion ballots cast.

What photo ID laws do accomplish is disproportionately barring African Americans from voting. For example, the 2012 American National Elections Study found that over 2.5 times as many African Americans (13 percent) lacked a valid photo ID as white people (5 percent). For African Americans living in households making less than $25,000 per year, that number increased dramatically to 39 percent. Alabama has estimated that 250,000 registered voters — around 10 percent of all of the state's registered voters — lack an ID required to vote.

To date, efforts to overturn Alabama's voter ID law have been unsuccessful. A lawsuit brought by the Greater Birmingham Ministries and Alabama NAACP challenging the photo ID requirement for having a disproportionate impact on minority voters is set to go to trial the same month the special election will take place.

Complicating administration of the state's voter ID law, in 2015 then-Gov. Robert Bentley (R) decided to close 31 driver's license offices where people could get ID to vote as well as register. While Bentley touted the move as a cost-savings measure, critics pointed out that the closures disproportionately affected the state's largely rural, impoverished, and majority African-American "Black Belt" region. Responding to the public outcry, the state reopened many of the offices but for fewer hours; a settlement later reached with the U.S. Department of Transportation after an investigation concluded Bentley's move violated the Civil Rights Act led to further expansion of operating hours at Black Belt offices, leaving things where they stood before the closures.

Polling place closures

In the wake of the Shelby decision, many states that were formerly covered by the Voting Rights Act's preapproval provision used their newfound freedom to close polling places. One study found that at least 868 polls were closed between 2012 and 2016 in states that formerly had federal oversight of voting. Though the study looked at only 18 of Alabama's 67 counties, it found at least 66 polling place closures in 12 of them.

A Facing South analysis that compared the Associated Press count of Alabama precincts in the 2012 election (2,711) to the New York Times' count in 2016 (2,522) found a loss of 189 precincts — an almost 7 percent decrease in a state where the population grew by nearly 2 percent from 2010 to 2016. An elections analyst from the Alabama's Secretary of State's office estimated that "about 2,500" polls would be open for the December special election.

Reclassifying voters' status

Earlier this year Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill's office sent out postcards confirming that people still lived at the address on their voter registrations. If the postcards were returned as undeliverable, the state then sent a forwardable postcard to those voters asking them to update their registration. If the state didn't get a reply to the second card, the voter would be moved to "inactive" status after 90 days. Once a voter is moved to inactive status, the clock begins ticking on their removal from the rolls, which comes after two federal elections in which the person doesn't vote.

However, being listed as an inactive voter could give someone the impression that their voter registration has expired. In addition, there has been considerable confusion surrounding the address confirmation process. ACLU of Alabama Executive Director Randall Marshall reports that some people who were able to vote in last November's general election and who didn't return the postcards — indicating they hadn't changed their address — were moved to inactive status anyway sometime between last November's general election and this year's primaries.

Others report not getting postcards at all — including Democratic state Rep. Patricia Todd, the state's first openly gay elected official. As she wrote in an Aug. 15 Facebook post, "I never got one and neither did my wife. I asked several other folks and they never received one."

It's unclear how many people might be affected by the confusion; a call to Merrill's office for more information wasn't immediately returned.

Resistance to re-enfranchising ex-felons

In May of this year, Alabama took a step to expand voting rights when it restored the franchise to people who had committed nonviolent felonies by defining "crimes of moral turpitude" — a vague classification that had been used historically to disenfranchise black voters in the state. The Southern Poverty Law Center estimated that the law would impact a "few thousand" people.

However, Merrill — a Republican who came under fire for touting the state's voter ID law at an event commemorating the Selma march — has declined to dedicate resources to informing people about the changes. In August a federal judge agreed, saying the state didn't have to inform people who previously were unable to vote that they can now register.

Given the lack of official action, the onus is now on advocacy groups to inform newly qualified voters of the change in their status.

(Facing South contributor Paul Blest provided research assistance for this story; he contributed $15 to Jones' campaign.)

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.