The limits of the Sandra Bland Act

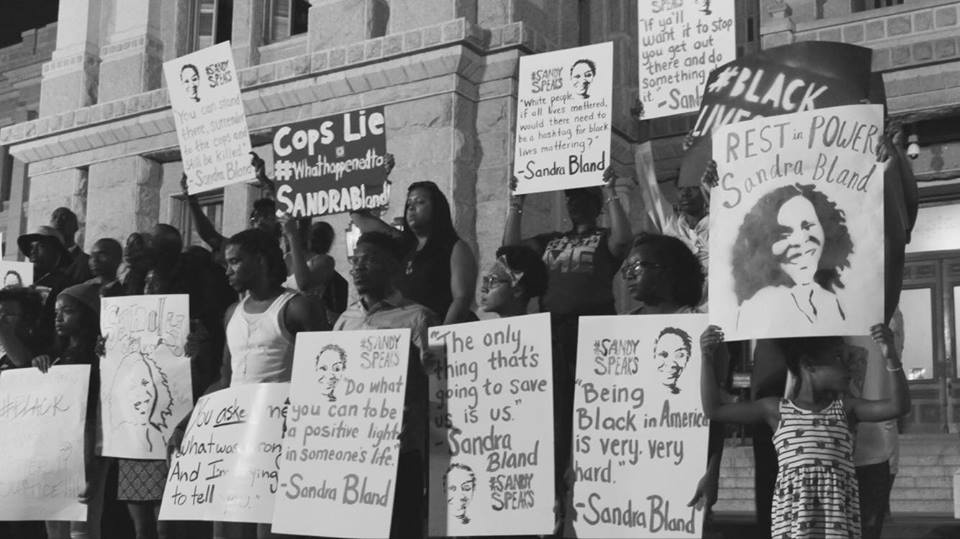

At a 2016 action, people gathered to remember Sandra Bland, who was found dead inside a Texas jail cell two years ago this week. (Photo from the Counter Balance: ATX Facebook page.)

Two years ago this week, Sandra Bland was found hanged in her jail cell in Waller County, Texas, three days after State Trooper Brian Encinia stopped her for failing to signal a lane change and threatened her with tasering, pushed her to the ground, and arrested her for refusing to put out her cigarette. She had been on her way to start a new job at Prairie View A&M, her alma mater.

Ruled a suicide, Bland's death drew national attention to the #SayHerName movement that has been working for years to shed light on the fact that, like their male counterparts, Black women and girls are disproportionately victims of police violence. Her death also drew attention to the plight of Black women who are disproportionately stuck in jail because they can't afford to make bail — a problem that can be particularly perilous to people like Bland, who struggled with mental health problems and had considered suicide previously, something her jailers knew.

Because Bland lived at the intersection of multiple identities — Black, woman, poor, health-challenged — advocates hoped that legislation to address the way she died would also be intersectional. But that's not how it worked out.

In its original form, the Sandra Bland Act, which was sponsored by Democratic Texas state Rep. Garnet Coleman of Houston, did address these intersections to a degree. It required a higher burden of proof for stopping and searching vehicles, and training for officers to prevent racial profiling. It banned arrests for offenses that are punishable by fines. It also would have mandated counseling for officers who engaged in racial profiling.

But that version of the bill drew criticism from law enforcement groups and Republican lawmakers and likely would have failed in the Republican-controlled Senate. So state Sen. John Whitmire, another Houston Democrat, introduced the bill that was passed unanimously and will take effect in September.

Largely focused on mental health, the law will divert people with mental health issues and substance mental illnesses to secure bond, and require that independent law enforcement agencies investigate jail deaths.

Bland's family has been critical of the law's limited vision.

"What this bill does in its current state renders Sandy invisible," said Bland's sister, Sharon Cooper.

Disconnecting vulnerabilities

It's true that Bland — like a disproportionate number of women in jails — lived with mental illness and depression. But disconnecting this part of her identity from her race, class, and gender fails to address the underlying causes of why she was arrested in the first place.

And because the law does not improve police accountability, it fails to address a critical larger issue: that people with disabilities, including mental illnesses like depression, are among those most affected by police violence.

According to a 2016 report from the Ruderman Family Foundation on media coverage of police use of force and disability, 27 percent of all Americans killed by police in 2015 had mental health issues. In addition, people with disabilities made up the majority of those killed in use-of-force cases that attracted widespread attention and overall were more likely to be unjustly harmed by law enforcement.

In reporting on such cases, the media often ignores the disability component or discusses it in ways that intensify ableism. For instance, in reporting on the 2014 New York Police Department chokehold killing of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, the media often discussed how Garner was a victim of racial prejudice and excessive force. But despite the fact that he suffered from asthma, diabetes and heart disease and his last words were, "I can't breathe," many reports failed to note how his disabilities made him especially vulnerable.

And disability is not unconnected to race: Because of environmental injustice and lack of access to health care in the U.S., people of color — and Black people in particular — are more likely to live with a disability.

"Disability intersects with other factors, such as race, class, gender, and sexuality to magnify the degrees of marginalization and increase the risk of violence," the Ruderman report notes.

Meanwhile, activists and family members of Bland disappointed by how the law that bears her name fails to adequately address the factors that led to her death continue to organize in her honor.

On July 13, the anniversary of her death, Texas-based nonprofit Counter Balance: ATX led dozens of people in a march from East Austin to the state capital to remember Bland as well as others who have died in police custody. As the marchers began their action — which was also used to connect people who are interested in criminal justice reform — they were led in prayer by spoken word artist, Selah Vie:

"We ask as we walk down this street … that we inflict some kind of thought or plant seeds with just our presence … Continue to use each and every one of us to ensure that things like this do not happen again and that we change laws that cause so much pain in people's lives."

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.