Remembering Katrina as a human rights disaster

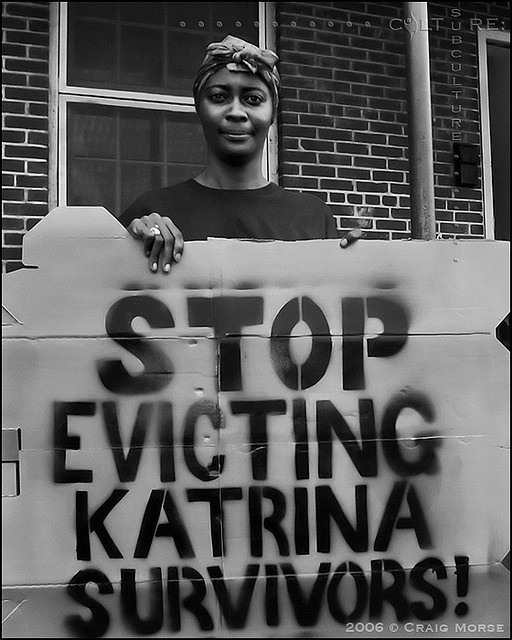

People displaced by Hurricane Katrina returned to their homes in many cases only to lose them to inequitable redevelopment schemes. (Photo by Craig Morse/Culture: Subculture Photography via Flickr.)

When Hurricane Katrina crashed into Louisiana in August 2005, it uprooted more than a million people, inflicted billions of dollars in economic damages and devastated entire communities across the Gulf Coast, some of which are still struggling 10 years later.

Katrina was more than an economic and social catastrophe; it was also a human rights disaster. The failure of federal and state officials to protect Gulf Coast residents from the storm, the botched response, and a deeply flawed recovery plan all revealed that the U.S. fell short in living up to international human rights standards it claimed to uphold.

Shortly after the storm, the Institute for Southern Studies — publisher of Facing South — launched Gulf Coast Reconstruction Watch, a special project to investigate the Katrina aftermath and recovery effort. Institute staff made several investigative trips to the region, interviewing more than 100 Gulf Coast leaders and analyzing thousands of pages of government records and private reports that resulted in several reports on the state of Gulf recovery.

The human rights dimension of the disaster became clear immediately after Katrina struck, when the media struggled to find the right words to describe the estimated 1.3 million people uprooted from their homes and scattered around the country. Some called them "refugees" — a term met with outrage by Gulf residents, since it officially applies to citizens of another country crossing borders. "Evacuees" was also inaccurate, since tens of thousands of people — largely due to a flawed and scandal-ridden emergency response — were never "evacuated" after the storm hit.

There is a more fitting term for those exiled by Katrina, coming from the arena of international human rights: "internally displaced persons." To protect the rights of those uprooted by wars and disasters within a country's borders, in the late 1990s the United Nations put forward — and the United States later endorsed — a set of 30 "Guiding Principles" for protecting the rights of internally displaced persons.

The standards clearly state that national governments have the "primary duty and responsibility" of preventing their people from being displaced, protecting their rights during displacement, and ensuring that those displaced are able to return to their communities in safety and with dignity.

In 2008, in partnership with the Brookings Institution, the Institute released the most in-depth report to date on the issue: "Hurricana Katrina and the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement" [pdf]. In conjunction with the release of the report, the Institute co-sponsored a forum in Washington, D.C. with Walter Kalin, the United Nations' Secretary General on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons (view a C-SPAN video of the forum here), as well as a fact-finding mission with Kalin to New Orleans and the Mississippi coast.

As Kalin stated during his visit to New Orleans:

Whether you're displaced in a rich country or a poor country, what remains the same is you need to get the help, the assistance of the authorities, of the communities, to be able to restart a normal life.

But as the 40-page Institute report described in stark detail, U.S. officials failed to live up to global human rights standards at every step of the process:

* FAILING TO PREVENT DISPLACEMENT: The U.N. guidelines state that governments should take all steps necessary to prevent displacement. Despite repeated official warnings of the impact a hurricane could have on New Orleans, the levee and storm protection system maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was decrepit and riddled with flaws, allowing the city to flood. Federal and state officials also allowed the rapid destruction of coastal Louisiana's precious wetlands — one of the best defenses against storm surges — to be destroyed at the rate of 25 to 35 square miles each year.

* FAILING TO PROTECT RIGHTS DURING DISPLACEMENT: The botched response to Katrina was marked by numerous violations of human rights standards. Tens of thousands of people were left stranded in New Orleans as floodwaters rose, with women, children, the poor and elderly put most at risk. Louisiana's federally-endorsed evacuation plan relied on automobiles as the primary means of escape if a storm hit, even though an estimated 120,000 people in New Orleans — one-third of the residents — didn't own a car. Evacuation buses — run by private companies receiving sweetheart federal contracts — didn't show up on time.

The human rights tragedies of the response multiplied. The lives of patients in hospitals and nursing homes were put at risk; 35 died of drowning in one nursing home alone. At Orleans Parish Prison, thousands of men, women and children as young as 10 — many being held for minor offenses — were effectively abandoned as floodwaters rose and the power went out. Tens of thousands were left in squalid conditions at the New Orleans Superdome and Convention Center. Despite being home to more than a million immigrants, storm bulletins were dispatched almost entirely in English.

* FAILING TO ENSURE A SAFE RETURN: After the TV crews left and media exposure waned, Gulf residents faced — and continue to confront — more obstacles to recovery that put the U.S. at odds with international human rights standards. Public housing was bulldozed and relief money was slow to get to homeowners, creating an affordable housing crisis in New Orleans and keeping thousands across the Gulf Coast from being able to return home. Months and years went by before schools, hospitals and other basic infrastructure were built, further slowing recovery.

Hundreds of millions in recovery dollars were squandered in no-bid and other dubious contracts, often with little state or federal oversight. African Americans were locked out of recovery jobs, while Latinos and other immigrants were locked in dangerous and exploitative jobs: In one 2006 survey, 46 percent of New Orleans recovery workers said they were cheated out getting their full pay.

The devastation of Katrina — and the disastrous governmental response — spurred some degree of change. FEMA, for example, received a far-reaching overhaul, and received high marks for its response to Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

It didn't lead to far-reaching changes in U.S. disaster policy like the Stafford Act, however, which was singled out for criticism after Katrina for its fragmented approach to response efforts and outdated formulas for channeling money into relief projects. Indeed, as the New Orleans-based group Advocates for Environmental Human Rights has argued, the U.N.'s Guiding Principles for internally displaced persons offer a useful framework for reforming the Stafford Act for more effective and equitable recovery planning.

Dozens of grassroots leaders and public interest groups took the human rights message about Katrina — relating to internally displaced persons and other issues — to various United Nations meetings. But the U.N. — where the U.S. is a permanent member of the Security Council — did little more than exert rhetorical pressure.

But, just as Southern civil rights activists appealed to the international community during the 1950s and 1960s, the call to treat Katrina as a global human rights issue served as a valuable educational and organizing tool. And today, as New Orleans and the Gulf Coast still struggle to reach a state of full and equitable renewal, activists like Monique Harden of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights continue to frame the problem as a human rights issue, 10 years later:

Human rights abuses taking place in New Orleans are being masked as 'resilience' and 'recovery' by elected officials, developers, and the tourism industry in the ten years after Katrina. We are supporting the resistance of African American, Vietnamese American, and Latino community organizers to the wide range of oppressive conditions that result from disaster profiteering.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.