Stamp would honor George Henry White, NC congressman deposed by racist voting laws

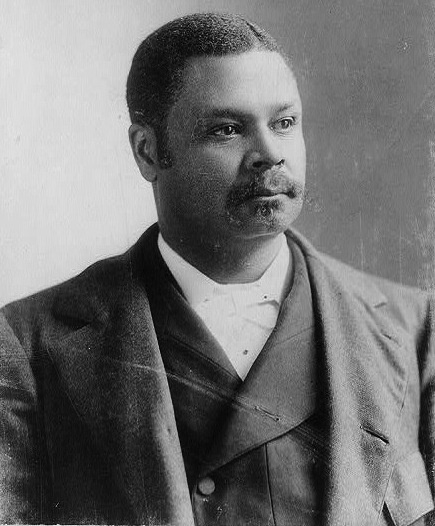

A bill was introduced in Congress this week to issue a commemorative postage stamp honoring George Henry White, an educator and former member of Congress from North Carolina who was driven out of office in 1901 by laws disenfranchising African Americans.

The same day a federal trial began over North Carolina's restrictive and racially discriminatory new voting law, one of the state's congressmen introduced a bill to honor a historic civil rights leader whose political career was cut short by earlier laws aimed at disenfranchising African Americans.

U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield's legislation would issue a commemorative U.S. postage stamp for George Henry White, a noted African-American educator, politician and civil rights advocate from North Carolina. White's service in Congress was abruptly ended at the dawn of the 20th century by the violent imposition of laws that drove blacks from the voting booth and public leadership positions across the South.

"George Henry White was a persistent and thoughtful advocate for his constituents and all African Americans," said Butterfield, a Democrat from Wilson. "He relentlessly stirred the conscience of both his Congressional colleagues and all Americans to embrace racial justice and equality for all people. His historic public service at the state and federal levels has made him an indelible and unique part of our nation's history, which is why he should be honored in this way."

White was born in eastern North Carolina's Bladen County in 1852, to a father who was a freeman farmer and a mother who was a slave, according to his congressional biography. White studied to be a schoolteacher at Howard University in Washington, D.C. and returned to North Carolina to work as an educator in New Bern. He served as a legal apprentice under a former Superior Court judge and was admitted to the state bar in 1879.

In 1880, White won election to the North Carolina House as a Republican, then the party of racial progress. In his single term there, he helped shepherd through a law creating schools to train more African-American teachers, and was hired as the principal of one. White returned to politics in 1884, winning a seat in the state Senate. He went on to serve as a solicitor and prosecuting attorney in eastern North Carolina and a delegate to the Republican National Convention.

In 1896 White was elected to the U.S. Congress representing what was then eastern North Carolina's mostly black 2nd District. His election was made possible by the rise of the interracial Fusionist movement, in which Populists and Republicans united to take control of the state from Democrats, then the party of white supremacy, and repealed laws that had been used to restrict the black vote. White was re-elected in 1898 despite viciously racist diatribes by North Carolina newspapers and violent efforts by Red Shirts — the paramilitary arm of the Democratic Party — to intimidate black voters. By then White was the only African American left in Congress following violent white supremacy campaigns throughout the South.

White used his congressional office to champion civil rights for African Americans and draw attention to the abusive treatment of blacks in the South. He introduced the first bill in Congress to make lynching a federal crime, though it failed amid opposition from his fellow Southern lawmakers.

Back home, North Carolina's Fusion movement was experiencing a violent backlash. Following two consecutive elections in which Fusionists won control of state government, white-supremacist Democrats regained power in 1898 with the help of the Red Shirts. But in the majority-black port city of Wilmington, the Fusionists won control of the municipal government. Two days after the election, a mob of some 2,000 white men rampaged through the city, killing as many as 60 people, destroying property in black neighborhoods and overthrowing the elected government. The rioters were joined by federal troops that had been sent to quell the violence. The incident was a turning point, ushering in an era of extreme racial oppression across not only North Carolina but the entire South.

The following year, North Carolina Democrats changed the state constitution to disenfranchise blacks, and White decided not to seek a third term in Congress. In his January 1901 farewell address, he criticized his white-supremacist colleagues and Democratic efforts to rob blacks of the vote. He detailed black progress since the Civil War and predicted that white supremacists would not be able to keep African Americans out of politics forever:

" … [W]hat the Negro was thirty-two years ago, is not a proper standard by which the Negro living on the threshold of the twentieth century should be measured. Since that time we have reduced the illiteracy of the race at least 45 percent. We have written and published nearly 500 books. We have nearly 800 newspapers, three of which are dailies. We have now in practice over 2,000 lawyers, and a corresponding number of doctors. We have accumulated over $12,000,000 worth of school property and about $40,000,000 worth of church property. We have about 140,000 farms and homes, valued in the neighborhood of $750,000,000, and personal property valued about $170,000,000. We have raised about $11,000,000 for educational purposes, and the property per-capita for every colored man, woman and child in the United States is estimated at $75. We are operating successfully several banks, commercial enterprises among our people in the South land, including one silk mill and one cotton factory. We have 32,000 teachers in the schools of the country; we have built, with the aid of our friends, about 20,000 churches, and support 7 colleges, 17 academies, 50 high schools, 5 law schools, 5 medical schools and 25 theological seminaries. We have over 600,000 acres of land in the South alone. The cotton produced, mainly by black labor, has increased from 4,669,770 bales in 1860 to 11,235,000 in 1899. All this was done under the most adverse circumstances.

We have done it in the face of lynching, burning at the stake, with the humiliation of "Jim Crow" laws, the disfranchisement of our male citizens, slander and degradation of our women, with the factories closed against us, no Negro permitted to be conductor on the railway cars … no Negro permitted to run as engineer on a locomotive, most of the mines closed against us. Labor unions — carpenters, painters, brick masons, machinists, hackmen and those supplying nearly every conceivable avocation for livelihood — have banded themselves together to better their condition, but, with few exceptions, the black face has been left out. The Negroes are seldom employed in our mercantile stores … With all these odds against us, we are forging our way ahead, slowly, perhaps, but surely … You may use our labor for two and a half centuries and then taunt us for our poverty, but let me remind you we will not always remain poor! You may withhold even the knowledge of how to read God's word and … then taunt us for our ignorance, but we would remind you that there is plenty of room at the top, and we are climbing … !

Mr. Chairman, before concluding my remarks I want to submit a brief recipe for the solution of the so-called "American Negro problem." He asks no special favors, but simply demands that he be given the same chance for existence, for earning a livelihood, for raising himself in the scales of manhood and womanhood, that are accorded to kindred nationalities. Treat him as a man … open the doors of industry to him … Help him to overcome his weaknesses, punish the crime-committing class by the courts of the land, measure the standard of the race by its best material, cease to mold prejudicial and unjust public sentiment against him, and … he will learn to support … and join in with that political party, that institution, whether secular or religious, in every community where he lives, which is destined to do the greatest good for the greatest number. Obliterate race hatred, party prejudice, and help us to achieve nobler ends, greater results and become satisfactory citizens to our brother in white.

This, Mr. Chairman, is perhaps the Negroes' temporary farewell to the American Congress; but … phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again …

It would be 1928 before the next African American was elected to Congress: Oscar DePriest, a Republican from the South Side of Chicago. North Carolina wouldn't send another African American to Congress until 1992, when Eva Clayton won a special election in the state's 1st District.

After leaving Congress, White moved his family first to Washington and then to Philadelphia, where he practiced law, founded a bank, and with backing from investors including educator Booker T. Washington and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar established a planned community for African Americans in southern New Jersey called Whitesboro. White became an officer in the National Afro-American Council, a national civil rights organization, and was an early member of the NAACP. He died in Philadelphia in 1918.

Butterfield's proposal to issue a commemorative stamp is part of a broader push to honor White. Organizers of that effort are also seeking a proclamation from President Obama next year to mark the 115th anniversary of White's departure from Congress and an exhibit on White in the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. For more on the efforts to honor White, visit www.georgehenrywhite.com.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.