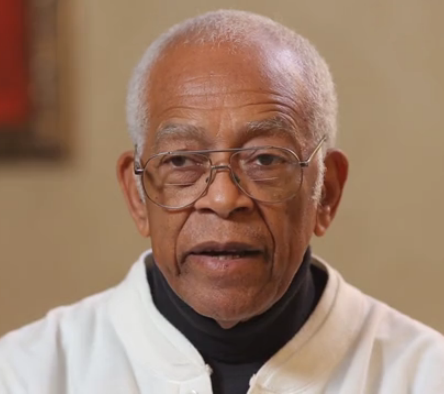

Elders of the movement

Hollis Watkins, a SNCC organizer and co-founder of Southern Echo, a group that works to develop grassroots African-American leaders in rural Mississippi, is among those who've been interviewed by the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation for an oral history of the civil rights movement. (Image is a still from the video below.)

The Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation funds organizations in the South working to move people and places out of poverty. The foundation recently launched a "Southern Voices" oral history project to capture the stories of Southern leaders working for social and economic justice. The first installment of the project focuses on elders in the movement who continue to work for the cause today. (Disclosure: The Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation is a funder of the Institute for Southern Studies.)

* * *

All over the American South, civic-minded people are working to improve communities by building coalitions and breaking down barriers to opportunity. The recent commemorations on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, honored the sacrifices of those who marched 50 years ago and the gains they brought to bear on our society. Many of those brave foot soldiers of the civil rights movement are still marching, tirelessly confronting new obstacles as they arise. While they remind us how far we've come from the days of segregation, their continued engagement tells us we haven't made it across the river.

Some of those elders generously sat down to share the rich and intensely personal stories of how they came to this work. Southwest Georgia Project Cofounder Shirley Sherrod described how her father's murder led to her involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee: "In 1965, my father was murdered by a white farmer in Baker County who was not prosecuted, so SNCC and Charles Sherrod and others who were working with him assisted us in starting the Baker County Movement. That summer, I was trying to register to vote, and every time I attempted to do so, the sheriff would be there to push me out of the courthouse. Didn't actually get to register until after the Voting Rights Act passed that summer, and so getting the right to vote, fighting for other rights -- we were trying to integrate schools, just fighting to help people get to a point where they could be safe and experience some of the things others were experiencing here in this country."

The Southwest Georgia Project started when Charles and Shirley Sherrod split with SNCC over whites' involvement. "In 1966, when Stokely Carmichael became the director of SNCC, Stokely felt that all whites needed to go and work in their own communities," said Shirley Sherrod. "We probably had 20 to 25 white people working with us during that time when Stokely was saying whites needed to leave. So we separated from SNCC at that point and later incorporated the Southwest Georgia Project. … We felt in order to bring about change, we needed the help of whites, whether they were from this area or not. And most of them were not; in fact, all of them were not. But we felt, too, that we needed each other in order to bring about the change that needed to happen here, and to mirror and set the example for other areas."

Southern Echo President Hollis Watkins was the first SNCC member in Mississippi, where he registered and educated voters. The son of sharecroppers, the seeds of his activism were planted in childhood: "I had to walk to school while white children on the bus rode by, splashed mud and water on us. We couldn't ride the bus. We could not go to the same school they went to. The equipment, the books and everything that we had at the school, were hand-me-down books. When they became obsolete for the white children, they were passed to us. I knew something was wrong with that. I didn't know exactly what. And I began to question people in general. I began to question God as to why He would allow such things to take place. As a part of that process, my father said to me once, he said, ‘Son, you always stand up for what's right, even if you're the only one standing.' And I began to look and see all of the things that I felt was wrong that was going on, and I said to myself, ‘These are the things that I've got to fight against because they're not right.' … I made a commitment that I would do everything I could, when I could, as long as I could until we get these situations straightened out. They still haven't been straightened out, so I'm still trying to live up to my commitment."

Like Watkins, Ralph Paige's activism began with voter registration. Paige, who retired this month as Executive Director of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives Land Assistance Fund, described how his focus shifted from polls to schools to land. "I thought voter registration, I thought stuff like that was the vehicle. Then of course, I taught school for a year and got a wild awakening being at a segregated system. … The Federation was being formed and…had set the course then to deal with economic justice in the South after the march from Selma to Montgomery."

Paige detailed how African-Americans owned and farmed acres and acres of land all over the South, but despite ostensible gains in the areas of integration and voting rights, there was no system of support or protection for black land owners. "There was never the infrastructure. There was never capital. There was never jobs. There was never anything for farmers to do. And land was being taken from them."

For decades, the network of cooperatives has played critical roles for its membership, nurtured a reputation for sustained support and planted deep roots for future generations of land owners. "We've stayed in communities for years. ... Some of the cooperatives been around, the next generation has taken over -- West Georgia Co-op, East Georgia Cooperative, Sea Island Small Farmers Cooperative. These are groups that have made a difference. The question is, has it made an economic difference? Yes."

Interviews with these leaders and several others comprise an oral history project documenting the critical work being done from the Deep South to Appalachia, from education to economic development, across lines of gender, race and politics. Some are veterans of the work; others are emerging leaders carrying it forward. Southern Voices aims to document decades of collective wisdom, share valuable lessons learned through experience and elevate the dialogue about the South. Over the next few months, you will hear visionaries describe in their own words how they're changing their communities for the better.

WATCH MORE:

Watkins faced death threats when he began his activism: "I prayed my nonviolence would never be tested."

During Freedom Summer, Watkins had to break the news to students that organizing could get them killed: "There were a lot of young people across the country that was willing to come to Mississippi and risk our lives to try to help make things better."

Watkins explains how he went from working with SNCC to forming Southern Echo: