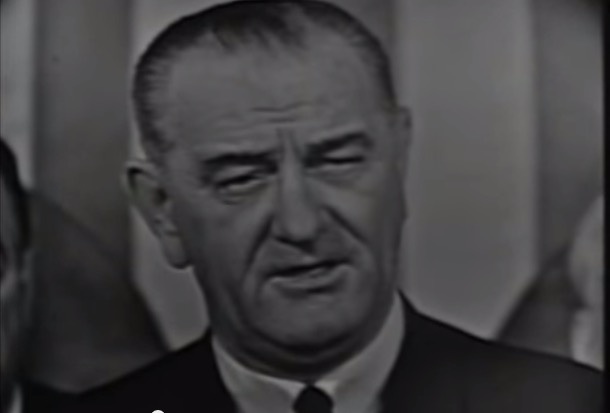

50 years since LBJ's historic voting rights speech

President Lyndon Johnson's 1965 address calling for passage of the Voting Rights Act is considered one of the finest pieces of presidential oratory in history.

Two weeks ago, tens of thousands of people came to Selma, Alabama to honor the 50th anniversary of the first Selma to Montgomery March. This week, on March 15, marks 50 years since President Lyndon Johnson's address to Congress -- only a week after "Bloody Sunday" -- calling for passage of the Voting Rights Act, the most durable achievement of the Selma march.

As Julian Zelizer notes in a thorough rundown of the speech's origins and aftermath in The Atlantic, Johnson's address was hailed as the best of his administration and one of the finest pieces of presidential oratory in history.

The debate over the level of Johnson's commitment to voting rights was reopened with his portrayal in the 2014 movie "Selma" as a reluctant ally. Whatever misgivings or calculations Johnson was making about pushing the Voting Rights Act, those were put aside after the bloody -- and widely televised -- events in Selma. With a draft bill already in hand, Johnson's team sprung into action, deciding that a national address from the president to Congress would launch a full-scale push to pass the bill:

The speech was written at break-neck speed. On the morning of March 15, presidential confidante Jack Valenti asked the 33-year-old Richard Goodwin, who had spent the previous night socializing and drinking, to write the speech. Valenti had assigned the job to someone else but Johnson said he wanted Goodwin. "Don't you know that a liberal Jew has his hands on the pulsebeat of America?" the president told Valenti.

Goodwin had about eight hours to finish the job. He pounded on his typewriter, with the images he had seen on television at the forefront of his mind. Goodwin didn't wrap up until about 7 p.m. He went so late into the day that he didn't have time to do any rewrites. He also didn't want to turn over the speech until the very end so that the president would not have time to tamper with the text.

In the speech, which was watched by 70 million people, Johnson framed voting rights as a defining and historic cause for the nation. "I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of Democracy," Johnson said. "There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem."

The speech was also important because in it, Johnson gave full credit to the civil rights movement, validating the struggle and -- indirectly -- undermining claims by the Southern opposition that the movement's leaders could be dismissed as "radicals" and "outside agitators." As Johnson said:

The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation. His demonstrations have been designed to call attention to injustice, designed to provoke change, designed to stir reform. He has called upon us to make good the promise of America.

Johnson then offered his ultimate endorsement of the movement by echoing one of its leading slogans, "We shall overcome."

Events unfolded rapidly: Two days later -- while 25,000 marchers continued their trek from Selma to Montgomery, with protection from federal troops -- Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) and Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) introduced a bill that quickly picked up 64 co-sponsors. The Senate passed the Voting Rights Act by 77-19, with only Southerners opposing it. (A key item of dispute was the formula for which areas would be covered by the act, a foreshadowing of the debates that now swirl around the VRA's re-authorization.) On July 9, the House followed, passing it on a vote of 333-85.

In Alabama, civil rights leader John Lewis watched the speech with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., where the room was moved to tears. "Dr. King started crying and we all cried." The speech itself, which was quickly recognized as historic, was also understood to be the result of an even more historic uprising of people organizing for change. As the editors of Life magazine observed afterwards:

What happened last week shows how public indignation, sweeping the country like chain lightening, can force a wise and necessary action that had been balked by partisanship and governmental apathy for nearly a hundred years.

Watch President Johnson's March 15, 1965 address to Congress here:

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.