Mixed picture for Southern unions

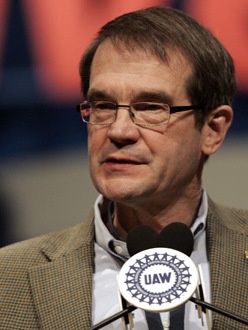

Bob King, president of the United Auto Workers, has launched high-profile campaigns to unionize auto plants in Mississippi and Tennessee, part of a broader interest among national unions to grow in Southern states. (Photo by Rebecca Cook/UAW.)

Last year, nearly 2.2 million workers in Southern states belonged to unions, and, despite a difficult climate for union organizing, five states -- Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana and Texas -- saw the total number of employees belonging to unions increase.

But overall, unions in the South followed the national trend of declining membership: According to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics data released last month, the percentage of workers belonging to unions -- also known as union density -- declined from 11.3 percent nationally in 2013 to 11.1 percent in 2014.

The latest BLS figures highlight the conflicted state of unions in the South. Thanks to right-to-work laws, restrictions on public-sector bargaining and other measures that have tilted the playing field against union organizing, Southern states have historically ranked among the lowest in union density.

That remains the case today. According to the BLS, in all 13 Southern states the percentage of workers belonging to unions was below the national average, with North Carolina having the nation's lowest union density at 1.9 percent.

But the story hasn't been all bad for unions in the South. In three states -- Arkansas, Florida and Louisiana -- union density actually increased, and in another four it remained about the same from the year before, as the following chart shows:

In 2013, labor pledged to step up its organizing in the South. Since then, unions have waged several high-profile campaigns, like a United Auto Workers' drive at a Volkswagen plant in Tennessee that came up short of winning a recognition election in early 2014 but ultimately led to VW partially recognizing the union.

In another UAW drive underway in Mississippi, Nissan recently declined to allow the U.S. State Department to mediate a complaint lodged by the union with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Labor has also invested in organizing fast food and other low-wage workers and in campaigns to raise the minimum wage in the South.

At the same time, unions have faced new efforts to rein in their ability to organize. Business and conservative groups are pushing "right to work" initiatives in the two Southern states without such laws, Kentucky and West Virginia. In North Carolina, lawmakers have introduced a bill that prevents the State Employees Association of N.C. from automatically collecting monthly dues.

One trend that may help Southern unions in the long-term: the rapidly-changing demographics of the region. Polls show the South's growing African-American, Asian and Latino communities are more receptive to unions and willing to join them. Which isn't a surprise: as writer Doug Henwood notes, the latest BLS data also shows that historically disenfranchised groups benefit the most from union membership:

Union status matters for wages: overall, unionized workers earned 27% more than nonunion (measured by median weekly earnings for full-time workers). The effect was especially pronounced for weaker, more discriminated-against demographic groups. The youngest group, aged 16–24, enjoyed a 28% union premium; the advantage declined with each successive cohort, down to 12% for the 65+ set. Women aged 25 and older enjoyed a 27% premium, compared to 15% for men. White men (16 and over) had a 20% union advantage, compared with 32% for white women; for black men, the premium was 29%, compared to 34% for black women; and for Hispanics, it was 44% for men and 46% for women.

Despite their relatively small numbers, unions in the South have shown they can still exert influence. This week, 4,000 members of the United Steelworkers went on strike at nine refinery and chemical plants -- including five in Texas and one in Kentucky -- that account for 10 percent of U.S. refinery capacity.

The workers, who are targeting oil giant Shell in demands for a 6 percent pay increase and better health and safety standards, have pledged to stay on strike until their demands are met. The USW warns that, if they are joined by the union's other national members, as much as 64 percent of the nation's fuel output could be disrupted.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.