Can Republicans show they're against Big Money, too?

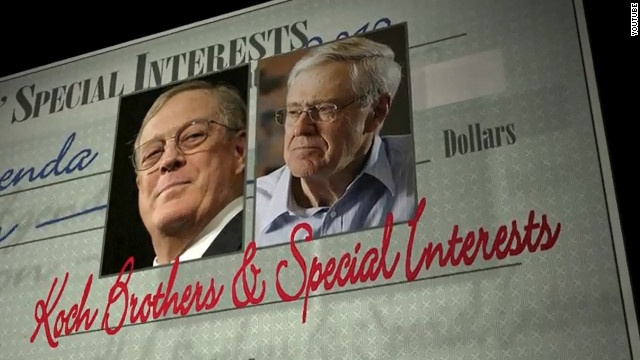

Spurred in part by Democratic attack ads, some Republicans are speaking out about Big Money's corrosive influence. But how far will Republicans go to cross big donors like the Koch brothers, who are vehemently opposed to campaign finance reforms? (Image is from a 2014 Patriot Majority TV ad.)

In 2014, Democrats made a big issue about Big Money in politics. With the billionaire Koch brothers bankrolling more than 40,000 ads -- mostly benefiting Republican candidates for U.S. Senate -- Democrats countered with TV spots and other messages attacking the Kochs for, in the words of then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, "actually trying to buy the country."

Now, some Republicans are seeking to show they're against Big Money influence, too. For good-government reform advocates, this is a welcome development -- a sign that curbing the influence of money in politics has bipartisan support. But how far will GOP support for campaign finance reform really go?

Last month, a group of operatives launched Take Back Our Republic, a nonprofit that promotes "conservative solutions to problems with the campaign finance system." The group was founded by John Pudner, a political consultant based in Alabama most recently known for advising the maverick campaign of David Bratt, who unseated House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in Virginia's 2014 Republican primary.

Pudner is open that one of his first challenges is convincing Republicans that curbing money in politics is "their" issue. As Pudner told The Washington Post, "To any conservative saying, 'Why are you getting involved in that? That's a liberal issue,' I would say, 'I think everyone is starting to realize that money in politics is an issue.'"

GOP strategist Mark McKinnon, who helped launch the group along with Federal Election Commission member Trevor Potter, echoed the sentiment:

As a Republican, I have long felt that [money in politics] was an issue that Republicans abandoned to Democrats at our expense. I've seen increasingly a real problem with not just a perception but a reality that Republicans are too closely wed to monied interests.

The concern is based in a strong reality: Polls consistently show that a large majority of voters are wary of the amount of money flooding into politics and its distorting influence on politics. Crucially, they feel the problem today is worse than usual: A July 2014 Democracy Corps poll [pdf] asked voters whether they thought Big Money spending was "wrong and leads to our elected officials representing the views of wealthy donors," or if "there has always been a lot of money in politics, and this spending is nothing new."

Sixty-five percent of those surveyed agreed with the first statement -- a message that the new era of billionaire super PACs and dark money spending is uniquely dangerous. Most significantly, that message resonated with 64 percent of independents and 54 percent of Republicans. As the pollsters concluded, "Business as usual is no longer an excuse."

But the problem for reformers has never been finding Republican voters who want to curb Big Money influence; there are plenty of polls showing that. There's also a rich tradition of GOP and right-leaning politicians who have railed against undue influence by the monied interests -- figures like archconservative Sen. Barry Goldwater, who said in 1983: "[O]ur nation is facing a crisis of liberty if we do not control campaign expenditures. We must prove that elective office is not for sale."

Key constituencies of importance to Republicans also favor reform as well. A recent poll by Small Business Majority, for example, found that 70 percent of small-business owners -- who don't have the resources to spend on elections like deep-pocketed corporations -- favor significant changes to how we finance campaigns.

The challenge has been agreeing on solutions. In the U.S. House, of the more than 140 co-sponsors of the Government By the People Act -- a small-donor, "clean elections" bill currently championed by the leading national reform groups -- only one is a Republican: North Carolina iconoclast Rep. Walter Jones. At the FEC, progress on stronger disclosure rules has been hamstrung by Republican opposition and partisan feuding.

At the state level, there has been more experimentation and bispartisanship in addressing Big Money influence. More than 20 states have some form of public financing to level the playing field for candidates seeking office, measures that have passed with bipartisan support (Maine being the most recent).

But those efforts have come under fire, often from the same ideological interests that have escalated spending in state-level elections. In North Carolina, a judicial public financing system that had passed with Republican backing was swiftly eliminated at the urging of millionaire GOP donor Art Pope, who first zeroed out funding for the program from his perch as the governor's budget director, and then pressured state legislators -- many of whom he helped spend money to elect -- to eliminate it entirely.

The North Carolina experience points to a central dilemma for conservative lawmakers: Despite widespread public frustration with Big Money influence, and promising leadership from a handful of GOP reformers, how far can they go in standing up to ideological donors like the Kochs, who fiercely oppose campaign finance rules -- and have pledged to spend $889 million in the run-up to 2016?

The answer is that reform is likely to happen only when the political costs of being tied to Big Money donors outweighs the benefits politicians receive from the millions of dollars spent on their behalf. In 2016, Democrats are planning to hammer Republicans again for their Koch ties. As Rep. Steve Israel (D-NY) said in an interview, "This issue polls very well. The more relentless [the Kochs] are, the more negative a brand we will make them."

But for reform to become a truly successful election-year issue, the message will have to come from nonpartisan groups with a proven long-term commitment to change, who can show the cost of Big Money influence to regular voters. As Adam Smith of the national reform group Every Voice told Politico, "I think it's important to keep doing this work going forward and to show how the policies big donors are trying to buy will hurt everyday people."

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.