From Selma to Citizens United: The contested struggle for one person, one vote

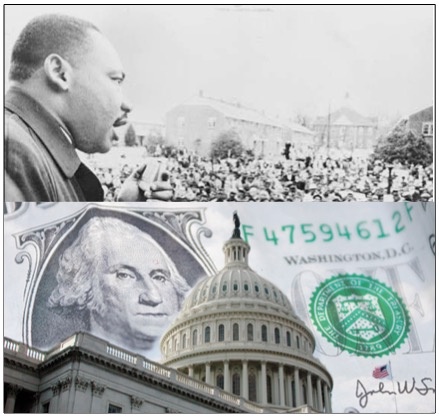

The 1965 Selma marches led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (pictured top) and others galvanized support for the Voting Rights Act and expanding voting access, but today key civil rights leaders argue that the growing power of Big Money in politics undermines the voice of ordinary voters. (Photos: U.S. Library of Congress; EveryVoice.org)

On Jan. 19, our country celebrates the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., half a century after his work -- chronicled in the recent Oscar-nominated movie "Selma" -- helped inspire passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Next week will also be the five-year anniversary of another momentous event for our democracy: the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which gave corporations and groups the right to spend unlimited money to influence elections.

The two anniversaries are more closely linked than many realize.

The 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches -- and the brutal backlash to them from Alabama state troopers -- galvanized national support for the Voting Rights Act, changing the balance of power in the South. Building on years of local organizing, "roughly a million new voters were registered within a few years after the [Voting Rights Act] became law," says historian Alexander Keyssar in his seminal book "The Right to Vote," "with African-American registration soaring to a record 62 percent."

While Selma and the Voting Rights Act strengthened the voice of ordinary voters, Citizens United has heightened the power of mega-rich donors. By opening the treasuries of companies, unions and other groups to limitless political spending, the decision has fueled a spending spree on elections, especially by outside groups not tied to a candidate.

According to a new report by the Brennan Center, outside spending in U.S. Senate races has doubled since 2010, to more than $486 million in 2014. In the 10 most competitive Senate races last year, outside groups accounted for the largest share of cash (47 percent). Having more money doesn't automatically guarantee victory for a candidate, but it certainly plays a role: By one estimate, the better-financed candidate in congressional races wins 91 percent of the time.

But there's another, more direct connection between the issues of protecting voting rights and curbing Big Money's influence: the role of skyrocketing election spending in exacerbating racial inequality.

As the think tank Demos documents in its December 2014 report, "Stacked Deck," the growing power of wealthy elites in our democracy has a profound racial bias. For one, the "donor class" of big contributors is overwhelmingly white: Demos' analysis found that in 2012 more than 90 percent of contributions of $200 or more in congressional elections came from majority white neighborhoods.

Race also plays a role in which candidates get backing from donors, and that in turn influences who gets elected. Demos reports [pdf] that "[c]andidates of color raised 47 percent less money than white candidates in 2006 state legislative races, and 64 percent less in the South." This is among the key reasons that, while whites make up less than two-thirds of the nation's population, they hold 90 percent of elected offices.

MONEY V. JUSTICE

The racial justice implications of Big Money in politics is especially clear in a relatively new spending battleground: state courts.

The courts have always been a key vehicle in the struggle to protect, expand and enforce civil rights, including the right to vote. Indeed, immediately after the Voting Rights Act passed, six Southern states immediately filed a legal challenge, one of many which made it way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Today, special interests are spending record amounts of money on court elections in the 38 states that elect justices to the bench. As a Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies report showed, more than $3 million poured into races for North Carolina's higher courts in 2014, the first election since state lawmakers -- with the help of millionaire donor and political operative Art Pope -- eliminated North Carolina's judicial public financing program.

The controversy over Big Money's attempted takeover of the courts is now coming to a head. Next week, the U.S. Supreme Court will begin hearing Williams-Yulee vs. The Florida Bar, a case involving a challenge to Florida's law barring judicial candidates from personally soliciting campaign contributions.

A constellation of groups have filed an amicus brief calling on the Supreme Court to uphold Florida's ban as a necessary measure to protect the integrity of state courts. As Bert Brandenburg of the court watchdog group Justice at Stake said in a statement unveiling the brief, "Our courts are different from the other two branches of government. If money influences what a legislator or a governor does, it reeks. But if campaign money influences a decision in the courtroom, it violates the Constitution."

Today, a growing number of civil rights and public interest leaders are seeing that voting rights and money in politics are two sides of the same coin: a common fight to bring our democracy closer to the ideal of "one person, one vote." In 2013, then-NAACP leader Ben Jealous explained the connection while announcing the civil rights group's involvement in a network fighting the Citizens United decision.

"We are facing a dual attack on our democracy -- everyday voters are being disenfranchised while corporations are being hyper-enfranchised," Jealous said. "We need to fix the fundamentals of our political system if we want to get down to solving our long-term problems."

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.