Could Duke Energy's coal ash be headed to a mine near you?

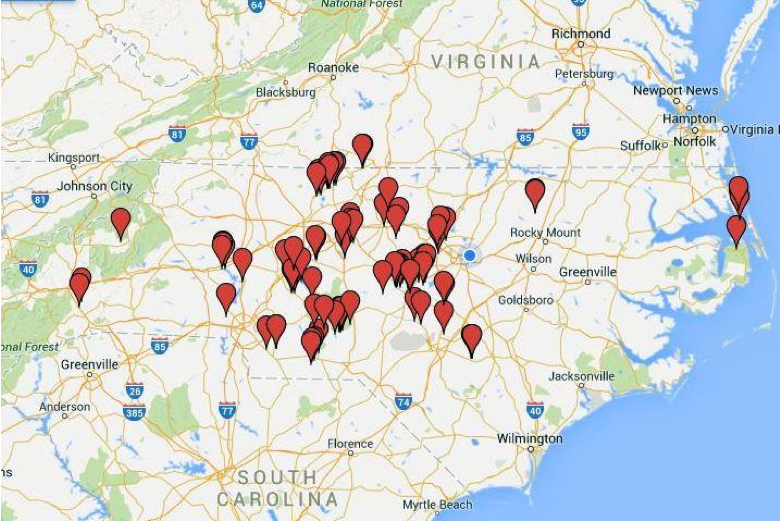

The locations of active and abandoned clay mines across North Carolina that could be targeted for coal ash dumping under a plan proposed by Duke Energy and its coal ash disposal contractor. (Map by the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League.)

A Duke Energy contractor is seeking permission from North Carolina regulators to move millions of tons of coal ash from existing dumpsites at the utility giant's power plants and place it in abandoned clay mines in Lee and Chatham counties.

But should the plan win state approval over the objections of local governments, environmental advocates worry that it could lead to dumping of coal ash in scores of former clay mines across the state. The waste left over after burning coal to generate electricity, coal ash contains potentially dangerous levels of toxins including arsenic, lead, thallium, and radioactive elements.

"If these two permits are approved, it will set a terrible precedent," said Therese Vick, an investigator with the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League (BREDL), a nonprofit environmental group based in North Carolina.

Last week BREDL released a report by Vick that shows the locations of 96 active and inactive clay mines in more than 20 counties across the state, from the mountains to the coast. Vick obtained the mine location data from the N.C. Division of Energy, Mines and Land Resources.

The dumping permits are being sought by Charah Inc., a coal ash services company based in Louisville, Kentucky. The permit applications indicate the coal ash would be moved from Duke Energy sites in North and South Carolina.

The quest to move the coal ash comes in the wake of last year's 39,000-ton spill into the Dan River from a retired Duke Energy coal-fired power plant in Rockingham County near the Virginia border. Most of the company's current coal ash dumpsites are located along rivers and other waterways and are leaking pollution to both surface and groundwater supplies, creating an urgent need to find safer storage solutions.

The Coal Ash Management Act passed last year by the N.C. General Assembly allows companies to dispose of the waste as "structural fill" to reclaim open pit mines, and it forbids local governments from imposing their own regulations on the practice. The Environmental Protection Agency's long-awaited coal ash rule issued last month treats coal ash as ordinary solid waste rather than as hazardous waste and is not expected to affect North Carolina's law.

Proponents of the plan note that the mines would first be lined, so essentially the sites would be treated like regulated landfills, which must have liners to prevent their contents from leaching into the groundwater. But even coal ash landfills are not without environmental problems.

BREDL points to the issues that have emerged at the Arrowhead landfill in Uniontown, Alabama that received the coal ash spilled in the 2008 TVA disaster in Tennessee. Residents of the high-poverty and mostly African-American community have complained about coal ash falling from trucks and spilling along roads, contaminated landfill runoff flowing into a nearby creek, and a foul smell. A civil rights complaint has been filed against the operation.

BREDL has also raised concerns that liners like those Charah is planning to install in the clay mines slated to receive the coal ash eventually fail. The group has called instead for solidifying coal ash with concrete and storing it in aboveground vaults on power plant property -- the "saltstone" disposal approach originally developed by the U.S. government for storing hazardous radioactive waste.

"The plan to spread coal ash all over the state is a public health nightmare," said BREDL Executive Director Lou Zeller. "This is an environmental justice issue."

To see an interactive map of the clay mines across North Carolina with details about their size and location, click here.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.