How are charitable nonprofits getting away with election-season political ads?

Charitable nonprofits are running ads calling out politicians during elections, like this one from the N.C. Environmental Partnership, despite IRS rules forbidding such groups from participating in campaigns for or against candidates. How do they get away with it?

Back in April, less than three weeks before the primary elections, the New York-based Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) launched a $700,000 television ad campaign in North Carolina slamming state Sen. Bill Cook, a Republican representing the northeastern part of the state, for his vote supporting a bill relaxing restrictions on landfills.

As a 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit, the NRDC is barred from supporting or opposing candidates for office. The Internal Revenue Service states that c3 groups, which are not required to disclose their donors, "are absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office." If they break this law, they could lose their tax-exempt status and pay a fine.

But ads like those sponsored by the NRDC occupy a legal gray area. Under current IRS law, an ad that praises or criticizes a candidate for office -- even if it's aired during an election -- might not be considered an attempt to influence the outcome of the vote if it does not explicitly urge viewers to vote for or against this candidate. The NRDC contends that because Cook faced no primary challenger and the ads did not urge viewers to vote against him, they were not election-related -- even though Cook faced a Democratic challenger in the fall's general election, which he won.

Without a direct reference to voting, ads like these can be considered "issue ads" that do not require donor disclosure. That means a tax-exempt organization can call out a candidate for elective office in an ad campaign, hide the donors who funded the ads, and still be considered in compliance with election and tax laws.

"The issue is whether the nonprofit is calling for candidates' election or defeat in a clear way, and whether it's using some of these magic words like 'elect,' 'defeat,' 'vote for,' et cetera," says Bob Hall, executive director of elections watchdog Democracy North Carolina.

However, the IRS rules are not very clear, says Hall: "There's not a bright line except the use of express advocacy language. If you avoid that, then you almost immediately get into this murky land of what is permissible and what is not."

The NRDC was not the only charitable nonprofit running ads about candidates during election season. The Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, another environmental nonprofit, spent $500,000 on an ad praising U.S. Sen. Kay Hagan (D-NC) in March and April, yet claimed it did not endorse her re-election campaign. And it's not happening only in North Carolina. For example, Change Agent Consortium, a c3 based in Detroit that works to address economic inequality, put out an ad in September criticizing Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder (R), who was running for re-election.

Dark money rising

501(c)(3)s are not the only nonprofits spending money on political ads, either. 501(c)(4) groups, or "social welfare" nonprofits, are allowed to make political expenditures and keep their donors secret as long as political activity is not their primary purpose. National groups such as the Koch brothers' Americans for Prosperity and Karl Rove's Crossroads GPS , as well as state groups such as Carolina Rising and N.C. Citizens for Protecting Our Schools, are c4s that spend large sums and leave their donors a mystery.

This money from c3 and c4 groups, often referred to as "dark money" because its sources are unknown, is on the rise. At least $169 million from undisclosed donors was spent during this year's congressional elections, an all-time high. New Federal Election Commission chief Ann Ravel said she plans to "at least make some incremental change in the disclosure of dark money," calling it an issue of "grave concern."

Meanwhile, reporting laws in North Carolina are also murky. The NRDC did report $411,000 in TV ads aimed at Cook to the N.C. Board of Elections, along with $20,700 in mailers targeting Cook on the same issue, classifying them as "electioneering communications."

State law defines an electioneering communication as "any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication, or mass mailing, or telephone phone bank" that "refers to a clearly identified candidate for elected office" but "does not expressly advocate for the election or defeat of that candidate." To qualify as electioneering, the communication must occur within 60 days of the start of absentee voting, or after Sept, 7 for general elections on even-numbered years. If a TV or radio ad, it must reach 50,000 or more individuals; if a mailing or phone bank, it must find at least 20,000 people.

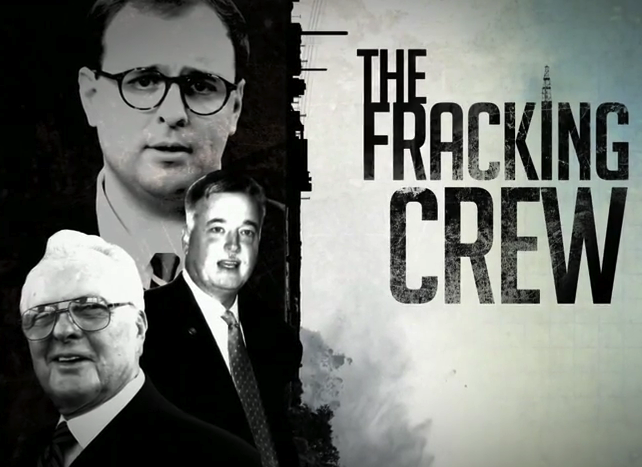

The NRDC also teamed up with the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), another 501(c)(3), and five other nonprofits to form the North Carolina Environmental Partnership (NCEP) to purchase ads and mailers. Aired beginning in March and aimed at "The Fracking Crew," the ads criticized Republican state Sens. Ronald Rabin, Wesley Meredith and Chad Barefoot for their pro-hydraulic fracturing votes.

Like the Cook ads, the NRDC does not consider these ads an attempt to influence elections. In a letter to the State Board of Elections, NRDC's director of policy advocacy, Wesley Warren, writes that the ads were timed to precede the 2014 legislative session, and "although no fracking legislation is pending … NRDC hopes that by encouraging North Carolinians to contact these legislators about fracking, the legislators will, in turn, work to protect our clean water and families' health from unsafe fracking if the opportunity arises…"

The legislators were clearly candidates for office, Hall says, but because the legislature was in session during the airing of some of these communications they could fit within an exemption from the disclosure requirement. According to state law, a "communication made while the General Assembly is in session" that "urges the audience to communicate with … members of the General Assembly concerning [a] piece of legislation or a solicitation of others" is not considered electioneering. However, the 2014 legislative session began on May 14, weeks after many of these ads hit the airwaves.

The NRDC and SELC reported to the state only the portion of those costs that pertained to Rabin. That's because while Rabin faced no Republican primary challenger, two Democrats were running against each other in the primary, as was also the case for Cook. Neither Meredith nor Barefoot nor their Democratic counterparts faced any primary challengers.

The NRDC has said that the only reason it reported any of this spending was due to "informal advice" from the Board of Elections. Warren wrote in his letter to the board that the group did not view its expenditures as electioneering but reported them "in the spirit of transparency."

The NCEP also issued ads opposing state Sen. Trudy Wade and state Reps. Tim Moffitt, Michele Presnell, Mike Stone, and Jamie Boles, all Republicans. According to Kantar Media/CMAC, the cost of these 20 unique ads, which ran over 5,000 times, totaled $1.7 million. There were no primary elections for these additional legislators' seats in either party, and no reports on the ad spending surfaced at the elections board.

While some of the TV ads were booked by the NCEP, the NRDC and SELC appear to have split the bill for the Rabin ads, sometimes reporting the same amount spent on the same day. Altogether, the NRDC and SELC reported $499,130 in TV ads against Rabin. Assuming Kantar Media's numbers are accurate*, that means the NCEP did not report over $1,200,000 of its ads.

The real numbers are likely much higher. If Rabin amounted to one-third of the ad spending for these "Fracking Crew" ads, those alone would have cost the group nearly $1.5 million.

* Kantar's estimates have sometimes proven to be far short of ad campaigns' actual costs. For example, the N.C. Chamber IE spent $345,000 on TV ads supporting N.C. Supreme Court candidates Jeanette Doran and Eric Levinson, but Kantar Media tracked only $99,000 of these expenses.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.