A Fourth of July anthology for the 'constructive patriot'

The great writer Mark Twain once defined a patriot as "the person who can holler the loudest without knowing what he is hollering about."

He was describing a phenomenon that political psychologists have come to call "blind patriotism," which they define as "an attachment to country characterized by unquestioning positive evaluation, staunch allegiance, and intolerance of criticism."

Here at Facing South, we suspect most of our readers, to the degree that they are patriots of any kind, are adherents of "constructive patriotism." That's defined as "an attachment to country characterized by support for questioning and criticism of current group practices that are intended to result in positive change."

We look forward to a Fourth of July holiday with less hollering and more thinking -- about the deeper meanings of Independence Day and the idea put forth in the Declaration of Independence that all people are created equal, in a nation still struggling to realize that ideal.

To mark the holiday, we share some critical cultural works that we turn to when we want to reflect amidst the flag-waving. What are the essays, speeches, poems, songs, etc. that spur you to think more deeply about what it means to be an American on this most American of holidays? Let us know in the comments.

* "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July" by Frederick Douglass (1852)

On July 5, 1852, abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass delivered an address to the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society that has come to be known as "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" Douglass, who escaped from slavery at the age of 21, contemplated the holiday's meaning in a nation that was still home to slaves:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy -- a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

Read Douglass' full speech here.

* "Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States" by the National Woman Suffrage Association (1876)

As Americans gathered to celebrate the nation's centennial at Philadelphia's Independence Square on July 4, 1876, a group of woman suffrage activists took the stage and presented U.S. Sen. Thomas Ferry of Michigan, who was officially representing his country at the ceremony, with a copy of the "Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States," written by Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton on behalf of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

The women then moved to an empty platform, where Anthony read the four-page document to the crowd that gathered. She began:

While the nation is buoyant with patriotism, and all hearts are attuned to praise, it is with sorrow we come to strike the one discordant note, on this 100th anniversary of our country's birth. When subjects of kings, emperors and czars from the old world join in our national jubilee, shall the women of the republic refuse to lay their hands with benedictions on the nation's head? Surveying America's exposition, surpassing in magnificence those of London, Paris and Vienna, shall we not rejoice at the success of the youngest rival among the nations of the earth? May not our hearts, in unison with all, swell with pride at her great achievements as a people: our free speech, free press, free schools, free church and the rapid progress we have made in material wealth, trade, commerce and the inventive arts? And we do rejoice in the success, thus far, of our experiment of self-government. Our faith is firm and unwavering in the broad principles of human rights proclaimed in 1776, not only as abstract truths but as the cornerstones of a republic. Yet we cannot forget, even in this glad hour, that while all men of every race and clime and condition, have been invested with the full rights of citizenship under our hospitable flag, all women still suffer the degradation of disfranchisement.

You can read the full declaration here.

* "The Fourth of July and Race Outrages" by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1903).

The New York Times published this essay by poet, novelist and playwright Dunbar on July 10, 1903, billing it as "bitter satire."

Dunbar opens by naming cities where recently there had been deadly racial violence: Belleville, Illinois, where an angry white mob had lynched a black man in a public square; Wilmington, North Carolina, where rioting white supremacists killed as many as 100 blacks and overthrew the multiracial elected government; and Evansville, Indiana, where white mobs attacked innocent black residents following the shooting of a police officer. He also mentions Kishineff (Kishinev) in the Russian Empire, where an anti-Semitic pogrom had left almost 50 Jews dead and 600 wounded -- an incident that President Theodore Roosevelt strongly condemned.

Observes Dunbar:

Sitting with closed lips over our own bloody deeds we accomplish the fine irony of a protest to Russia. Contemplating with placid eyes the destruction of all the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution stood for, we celebrate the thing which our own action proclaims we do not believe in.

Read the full essay here.

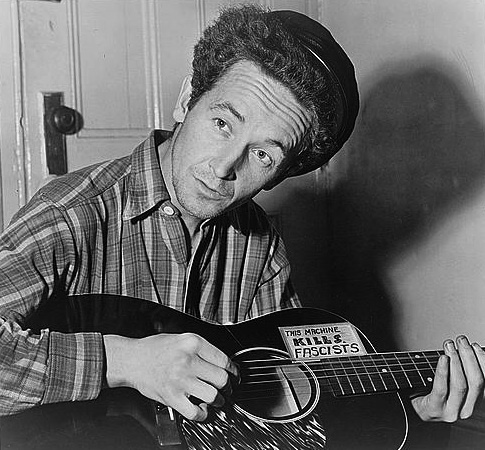

* "This Land Is Your Land" by Woody Guthrie (1940).

Here's one to break out during patriotic sing-alongs. Regarded as a sort of unofficial national anthem by many Americans, it was penned by a Communist sympathizer as a populist corrective to Irving Berlin's "God Bless America," which Guthrie considered complacent.

While most of us are familiar with the lines about the redwood forest and the golden valley, the original version of the song has lesser-known verses that critique American inequality:

Was a high wall there that tried to stop me

A sign was painted said: Private Property,

But on the back side it didn't say nothing --

This land was made for you and me.

One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple

By the Relief Office I saw my people --

As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering if

This land was made for you and me.

Check out this version of Guthrie's song, performed by music legends Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen at a concert during President Obama's 2009 inauguration:

* "My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying," Buffy Sainte-Marie (1966).

On a day dedicated to celebrating the birth of the United States, we might think about the people who were here before the colonizers, and consider what colonization meant for them.

Among the most moving expressions of an indigenous perspective on American colonization is Cree musician, educator and activist Buffy Sainte-Marie's song "My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying" from her 1966 album, "Little Wheel Spin and Spin." With its lyrical reference to the patriotic song also known as "America," Sainte-Marie's song begins:

Now that your big eyes have finally opened

Now that you're wondering how must they feel

Meaning them that you've chased across America's movie screens

Now that you're wondering, "How can it be real?"

That the ones you've called colorful, noble and proud

In your school propaganda

They starve in their splendor

You've asked for my comment I simply will render

My country 'tis of thy people you're dying.

Here's a video of Sainte-Marie performing the song on "Rainbow Quest," Pete Seeger's 1960s TV series:

* "Born in the USA," Bruce Springsteen (1984)

Though Springsteen's song been often misunderstood as a nationalistic anthem -- perhaps most famously by the campaign of President Ronald Reagan -- its lyrics are actually about the ruinous effect of war on Americans. The opening lines:

Born down in a dead man's town

The first kick I took was when I hit the ground

You end up like a dog that's been beat too much

Till you spend half your life just covering up

Born in the U.S.A.

I was born in the U.S.A.

I was born in the U.S.A.

Born in the U.S.A.

Got in a little hometown jam

So they put a rifle in my hand

Sent me off to a foreign land

To go and kill the yellow man

Born in the U.S.A.

I was born in the U.S.A.

I was born in the U.S.A.

I was born in the U.S.A.

Born in the U.S.A.

The lyrics about the jobless vet going "down to see [his] V.A. man" who said "Son, don't you understand" have particular resonance today given the recent Veterans Health Administration scandal, part of the longstanding outrage of sending people off to fight and neglecting them when they return home.

Watch the video here:

* "Patriotism and Ambivalence," Rogelio Saenz (2010).

For the Fourth of July in 2010, The New York Times invited six writers and historians to contemplate what the holiday means to immigrants, how different generations see the day, and how their views change over time.

Among the contributors was Rogelio Saenz, then a professor of sociology at Texas A&M University who now serves as dean of the College of Public Policy at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Saenz wrote about how some Latinos feel they are not seen as "real Americans" and how that affects their view of the holiday:

Indeed, many other Latinos possess ancestors who have been in this country for many generations, yet they continue to feel isolated because they are not really seen by mainstream America as part of the national fabric. Even though they may take a day off from work, do the cookout thing, and view firework displays, they do not really feel American or feel that other Americans do not see them as belonging to this country.

You can read Saenz's full essay -- along with others by Joshua Halberstam, Kica Matos, Thomas Glave, David A. Hollinger, and Hiroshi Motomura -- here.

* "With Civil War's Rancor Faded, Reasons to Celebrate," Campbell Robertson, (2013).

Vicksburg, Mississippi has been called the city that did not celebrate the Fourth of July because a brutal 47-day siege during the Civil War ended with its surrender on that day in 1863.

But last year, New York Times reporter Campbell Robertson visited the city and told the fuller story: that the African Americans of Vicksburg have long celebrated the holiday precisely because of what happened on that date:

"We celebrated the Fourth of July," said Yolande Robbins, 73, whose great-grandmother was a slave here and who know runs her father's funeral home. "Our grandparents told us that the real reason we celebrated the Fourth of July is because Vicksburg fell."

Read Robertson's report here.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.