South still least segregated for black students, but progress stuck in 1967

This week marks the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing school segregation. To mark the occasion, a civil rights think tank has released two reports that warn of growing resegregation in schools nationwide and in North Carolina in particular.

"Brown was a major accomplishment and we should rightfully be proud," said co-author Gary Orfield, co-director of UCLA's Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles that carried out the studies. "But a real celebration should also involve thinking seriously about why the country has turned away from the goal of Brown and accepted deepening polarization and inequality in our schools."

Research has found that minority-segregated schools tend to have fewer experienced teachers, greater teacher turnover, inadequate resources, and higher dropout rates. Desegregated schools, on the other hand, are linked to benefits including improved academic achievement for minority students with no decline for white students, improved critical thinking skills, and reduction in students' willingness to accept stereotypes.

Among the key findings of one of the reports, "Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future":

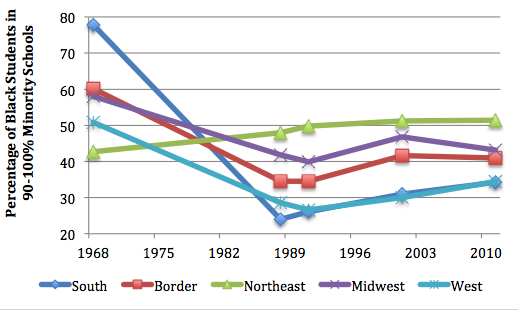

* Despite some claims to the contrary, the South has not reverted to pre-Brown levels of segregation. However, it's lost all of the additional progress made toward school integration after 1967. Nevertheless, for black students, the South is still the least segregated region.

* The Supreme Court has fundamentally changed desegregation law since the 1990s, leading to the end of many district desegregation plans. Among the large school districts that have experienced increased segregation as a result are Charlotte, North Carolina; Henrico County, Virginia; and Pinellas County, Florida.

* The South, which has always been home to the most black students, now has more Latinos than blacks and is what the authors call a "profoundly tri-racial region."

* Segregation of blacks is highest in the Northeast, while California is the state where Latinos are most segregated.

The report offers recommendations for creating and maintaining integrated schools. They include developing student assignment policies that consider race among other factors, altering school choice plans to ensure they promote diversity, promoting collaboration between fair housing efforts and school policies, and recruiting more diverse teaching staff while training current staff.

This week the Civil Rights Project also released a report on school resegregation in North Carolina specifically, part of a special series on public schools in Eastern states.

Once a leader in desegregation, North Carolina -- though still less segregated than the U.S. overall -- has experienced a tripling of intensely segregated schools since 1989. They now account for a full 10 percent of the state's schools, up from 3 percent a quarter-century ago. An intensely segregated school is defined as one where minorities make up 90 percent or more of the student body.

In Greensboro -- the first Southern city to announce that it would comply with the May 17, 1954 Brown decision -- the share of intensely segregated schools jumped from 0.7 percent in 1989 to 15.8 percent in 2010. In Charlotte, 20.2 percent of schools were intensely segregated in 2010, up from 0.1 percent in 1989.

"It is very sad for me to see statistics showing a level of segregation that looks like Detroit or Chicago in parts of North Carolina where there had been nothing like that for a third of a century," Orfield wrote in his foreword to the report.

In the Raleigh metro area -- part of the Wake County district that in 2000 adopted a groundbreaking desegregation plan based on socioeconomic status -- the share of intensely segregated schools increased over the last two decades but remained relatively small in 2010 at less than 3 percent. In recent years, however, the district's integration plan has come under political attack, with a resulting shift toward emphasizing neighborhood schools.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.