Pro-union Nissan worker in Mississippi: The UAW-VW vote in Chattanooga only 'made us stronger'

By Joe Atkins, Labor South

Chip Wells, 43, an 11-year veteran at the 5,200-employee Nissan plant in Canton, Miss., says the recent bad news coming out of the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., did nothing to deter him and fellow pro-union Nissan workers from their campaign to join the United Auto Workers.

"People think that derailed us," says Wells, who works in Nissan's paint department, "but we think it made us stronger. That plant (in Chattanooga) was only opened for two years. They're still in the honeymoon phase."

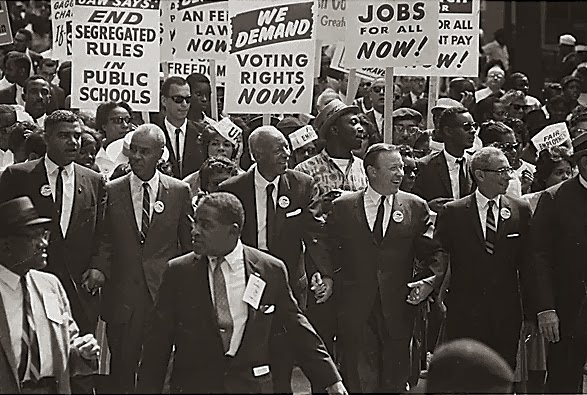

The UAW "made some mistakes and they realize it," he says. "The demographics were different. Here labor rights are civil rights, actually human rights."

Wells expects a union election at Nissan's Canton plant by this summer. UAW President Bob King has tied his legacy to organizing in the South, and he plans to step down in June.

Wells says he traveled to Chattanooga to witness the Valentine's Day 712-626 vote rejecting UAW representation at the Volkswagen plant. "When we got there, they'd lost by 43 or however many there were. Some were crying. To me, they took it too hard. We don't need to be feeling like this."

Despite its closeness, the vote at the 1,560-worker Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga was called "a devastating loss that derails the United Auto Workers union's effort to organize Southern factories," by the Associated Press. The New York Times called it a "stinging defeat" for the UAW. Others talked of a "fatal blow" to UAW hopes to organize the foreign auto plants in the South.

What's missing from this picture is the nine-year-old campaign in Canton that has grown from small gatherings of activists, organizers, and a handful of courageous workers in 2005 to rallies of hundreds at local churches and college auditoriums. Caravans of workers, students and activists have traveling to trade shows across the country and as far away as South Africa and Brazil, where national labor leaders have pledged their support.

Even beyond Nissan in Canton, the UAW has an active campaign at the Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Ala., where, as with the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, the potential exists to establish a German-style works council with the UAW representing workers on key issues such as wages, benefits and working conditions.

In Chattanooga, the UAW should have insisted on more time to establish a firm foundation of community support that would withstand the inevitable anti-union political-business-media juggernaut. U.S. Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., Tennessee Republican Gov. Bill Haslam and outside groups like Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform led a virulent campaign warning of lost jobs, plant closings and a Detroit-like future if the UAW won.

The UAW underestimated the forces aligned against it. The union figured that Volkswagen's own willingness to allow a fair election and creation of a German-style works council at the plant was sufficient to ensure victory. The UAW was wrong.

Mississippi is different.

The workers who voted in Chattanooga were predominantly white in a Republican stronghold in a Republican-dominated state. Mississippi is also Republican-ruled, but the Nissan plant has an 80-percent black workforce and is located near the capital city of Jackson, one of the state's few Democratic strongholds. Then there's the legacy of civil rights in Mississippi.

"The politicians are going to get involved, and it is going to be ugly," Well says. "Down here in the South this is a mindset. This is the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer. They didn't like people coming in from the outside to tell them how to do their business. They look at the UAW the same way."

Indeed, the summer of 2014 will mark the 50th anniversary of the murders of civil rights activists Andrew Goodman, Mickey Schwerner and James Chaney in Neshoba County, Miss. Goodman and Schwerner came to Mississippi as part of a wave of young idealists hoping to help establish freedom and democracy during what became known as "Freedom Summer." Chaney was a native Mississippian and the only black among the three.

"Labor Right Are Civil Rights" was the banner carried by a delegation of preachers, activists and workers from Canton to the recent North American International Auto Show in Detroit. That slogan has inspired a network of students at historically black colleges and universities who are constantly working their computers and iPhones to build support for a union election at the Nissan plant.

"Our movement is moving," says Hayat Mohammad, a 19-year-old English major at predominantly black Tougaloo College near Jackson and a leader of the Mississippi Student Justice Alliance. "We have such amazing talent -- photographers, journalists -- such active young people. Nissan is feeling the pressure."

What the workers in Canton and Chattanooga face is what workers face all across the South. Yet union campaigns were successful at places such as Smithfield Foods in North Carolina in recent years and, decades before, with the textile giant J.P. Stevens in North Carolina. The Farm Labor Organizing Committee and Coalition of Immokalee Workers have also won better wages and conditions for migrant workers in North Carolina and Florida. These campaigns were all hard-fought and took years.

"You've got to train your local leaders, get your core group together and train them," veteran Southern labor organizer Danny Forsyth once told me in an interview. "Whenever I left town, the local leadership could do what was necessary to do."

Forsyth knows what he's talking about. Over a four-year period in the 1980s, he helped secure 20 victories out of 22 campaigns in the South. That includes the successful battle to establish a union at the giant Pillowtex textile mill in Kannapolis, N.C., in 1999.

The best organizing is from the ground up, Forsyth said, and it utilizes the same methods espoused by famed community organizer Saul Alinsky. Workers learn where they fit in vis-à-vis the existing power structure in a plant and see they have power, too. Community is key to organizing, Forsyth said.

A workers' organizing committee has a firm foothold at the Nissan-Canton plant, Chip Wells says. "We are fighting for each other. We love each other. We've gotten to know each other, really become friends from not even knowing each other a couple years ago. If something happens to one, we all get behind each other."

Anti-union pressures inside the Canton plant continue, Wells says. Plant leaders no longer subject workers to the anti-union videos that were once a staple, but they still "tell us how many plants (the UAW) closed down, insinuate things."

Unlike Volkswagen, Nissan has given no indication that it will allow a fair, intimidation-free election at the Canton plant. Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn has been a vocal opponent of unions at his company's Southern plants.

Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant, a Republican, has already publicly invited outside groups to come in and help fight unions at the auto plants in his state. He and other Republican leaders can be expected to do what Haslam and Corker did in Tennessee.

"It is our blood, sweat and tears that is in these vehicles," Nissan worker Wells says. "We are prepared for the politicians."

Tags

Joe Atkins

Joe Atkins is a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi and author of "Covering for the Bosses: Labor and the Southern Press." A veteran journalist, Atkins previously worked as the congressional correspondent with Gannett New Service's Washington bureau and with newspapers in North Carolina and Mississippi.