ReVisioning Black History Month: Linking African American and Latino histories

By Paul Ortiz, Beacon Broadside

Black History Month is more important than ever. To understand how this nation traveled from colonialism to independence, slavery to freedom, and segregation to civil rights, we must place the lives, aspirations, and thoughts of African Americans at the center of US history. The first martyr of the American Revolution was Crispus Attucks, a sailor of African and Native American heritage who fell in the Boston Massacre. John Hancock honored Attuck's memory by observing, "Who taught the British soldier that he might be defeated? Who dared look into his eyes? I place, therefore, this Crispus Attucks in the foremost rank of the men that dared." By the end of the Revolution black troops composed approximately one out of every five soldiers in George Washington's Continental Army.

Abraham Lincoln credited African American labor power as well as courage on the battlefield with turning the tide of the Civil War. In an interview with John T. Mills, President Lincoln asserted "Abandon all the posts now garrisoned by black men, take one hundred and fifty thousand men from our side and put them in the battle-field or corn-field against us, and we would be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks."

Beyond these powerful narratives, John Brown Childs has argued in his essay, "Crossroads: Towards a Transcommunal Black History Month in the Multicultural United States of the 21st Century," that we need to broaden the scope and scale of Black History Month beyond the borders of the United States and to think of the ways that Latinos, Native Americans, and others have played critical roles in African American history. Historically speaking, African Americans have often connected questions of self-determination and equality at home with the fates of oppressed people in Latin America, Africa, and the Global South generally. In 1825, free African Americans in Baltimore gathered to celebrate the 21st anniversary of Haitian Independence and offered a public tribute to "Washington, Toussaint, and Bolívar -- Unequalled in fame -- the friends of mankind -- the glorious advocates of Liberty." By this gesture, African Americans joined their own aspirations for freedom with the emancipation of their brothers and sisters in Latin America and the Caribbean. The commemoration promoted an understanding of the intimate connections between movements for liberty throughout the Americas.

Simón Bolívar grew to become a cherished figure in African American communities because of his June and July decrees of 1816 which freed enslaved people willing to fight on behalf of the Third Republic of Venezuela. These decrees followed Bolívar's legendary meeting with Haitian president Alexandre Pétion who promised support for "El Libertador" against Spain in return for a pledge to end slavery in Central America. African Americans understood that the great leaders of the Latin American wars of independence relied upon the masses to defeat colonialism. The black newspaper, Freedom's Journal reminded its readers in 1827 that "The master spirits that achieved the Revolution in Colombia and Mexico…What is the complexion of the common soldiery of these states? Has not the independence of their country from the vassalage and bondage of Old Spain, been accomplished by troops composed of Negroes, Mulattoes and Indians?"

In the context of Black History Month, the African American century beginning in the 1820s and extending to the eve of the Great Depression was an epoch of Pan-Africanism, anti-imperialism, and expressions of solidarity with a pantheon of Latin America's greatest freedom fighters including Vicente Guerrero, José María Morelos, José Martí, Antonio Maceo, and Augusto Sandino -- among many others. Nearly a century after African Americans in Baltimore had honored Bolívar, the Negro World, the organ of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, joined the people of Peru in commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Ayacucho, considered to be the final major battle of the Latin American Independence wars. By raising the bar of emancipation to encompass liberation struggles in Latin America, African Americans articulated an inclusive, internationalist vision of freedom.

W. E. B. Du Bois articulated such a vision at the 1928 national convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Los Angeles. Dr. Du Bois explained that African Americans were fighting to regain the right to vote in order to secure their own rights as well as to check the power of American imperialism in Latin America and the rest of the world. "The American ballot must be re-established on a real basis of intelligence and character," Du Bois asserted. He continued:

Only in such way can this nation face the tremendous problems before it: the problem of free speech, an unsubsidized press and civil liberty for all people; the problem of imperialism and the emancipation of Haiti, Nicaragua, Cuba, the Philippines, and Hawaii from the government of American banks; the overshadowing problem of peace among the nations and of decent and intelligent co-operation in the real advancement of the natives of Africa and Asia, together with freedom for China, India and Egypt.

At the same time, African Americans were closely watching the progress of the Nicaraguan liberation struggle vis-à-vis the "government of American banks" and the US Marine invasion force. Many blacks rooted for the people that the Pittsburgh Courier called "the Indians and Negroes among the population of Northwest Nicaragua" who composed the rank-and-file of Augusto Sandino's rebel forces. While the New York Times scornfully referred to Sandino as a criminal, a rejoinder in the Amsterdam News argued that: "Sandino has been called a bandit, but his words are not those of a bandit; they would have fitted the mouth of George Washington when he was fighting the British. The worst feature of the business is the curtailing of Latin American freedom of speech by American military power. In Nicaragua, the [US] marines seem to be repeating their record in Haiti and the Virgin Islands. Thinkers will wish to know whether this country is to remain a republic or become an empire."

In recent years, African Americans and Latinos have carried on the practice of honoring African American experiences in an effort to infuse contemporary political struggles with historical wisdom. In 2007, Latino and African American meatpackers at Smithfield Foods in North Carolina joined hands and went on strike to demand that the company observe Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a paid holiday. Union organizer Eduardo Peña noted, "We've got Latino workers here ready to walk out for the holiday. I hear them saying things like, 'People assume that we don't know who King was -- his struggle was the same struggle we're going through now.'" The workers incorporated the battle over Martin Luther King, Jr. Day into their union organizing campaign -- and ultimately won.

In 2010, community organizers in Arizona struggling against racist immigration policies consciously drew lessons from the 1960s civil rights movement for inspiration and strategic insights. Immigration rights activists invited veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to address them in workshops, and they marched together with banners reading "From Selma to Phoenix, from Civil Rights to Human Rights." Across the country, African Americans and Latinos bridged sometimes tense relationships by inviting each other to speak about shared visions. In 2008, Janet Murguía, president and CEO of the National Council of La Raza, became the first Latina to be the keynote speaker for Birmingham's annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Unity Breakfast. In 2010, Chuck D transformed the 1991 Public Enemy song "By the Time I Get to Arizona," originally penned to protest Arizona's refusal to celebrate MLK Day, into a protest against oppressive immigration policies aimed against Latinos.

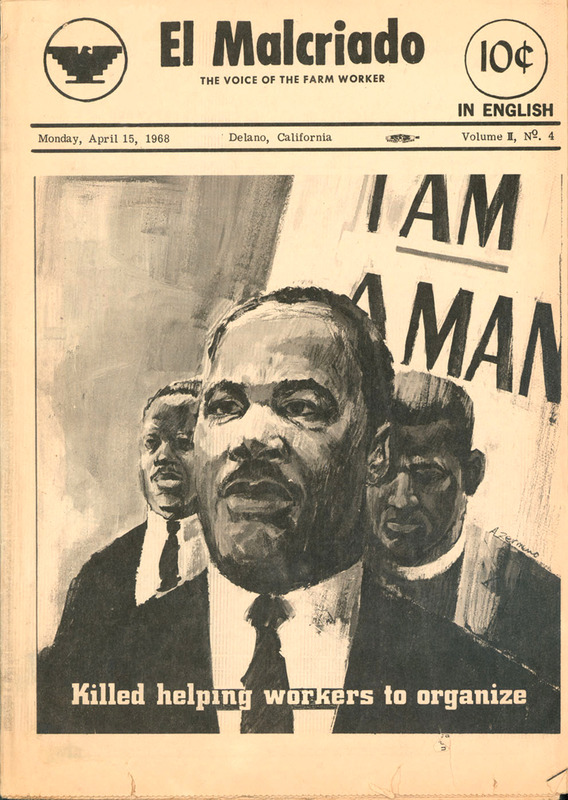

The life and example of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave African Americans and Latinos new ways to infuse Black History Month with aspirations for social change. El Malcriado ("The Troublemaker") was the bilingual newspaper published by the United Farm Workers. The April 15, 1968 issue was dedicated to the memory of Dr. King, and El Malcriado’s editors pointedly titled this edition, "Killed Helping Workers to Organize." The issue's writers chronicled Dr. King's defense of workers' rights as well as his vocal opposition to American imperialism and the Vietnam War. The issue's cover featured a drawing of King leading a protest march with the Memphis sanitation workers' iconic "I Am A Man" picket sign in the background. This edition of El Malcriado was an homage to the overlapping chronicles of Latina and African American freedom struggles.

A few months later, El Malcriado announced an educational workshop for the children of striking grape workers in Delano, California. The students would be immersed in studies of Mexican folklore and art. In addition, the pupils would be taught lessons about the lives of Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, "and the leaders of the farm workers' Cause." It is the curriculum taught to these children of striking farm workers that Our Separate Struggles Are Really One seeks to promote, re-envisioning American history as a shared narrative of struggle -- for justice, dignity, and equality for all.

* * *

Paul Ortiz is director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program and associate professor of history at the University of Florida. He is currently writing Our Separate Struggles Are Really One: African American and Latino Histories, to be published by Beacon Press.

Tags

Paul Ortiz

Paul Ortiz is the director of the award-winning Samuel Proctor Oral History Program and associate professor of history at the University of Florida. He is a former board member of the nonprofit Institute for Southern Studies, which publishes Facing South.