On North Carolina's high court, corruption worse than West Virginia?

It was a judicial corruption case shocking in its brazenness -- even for West Virginia, a state renowned for its history of corruption.

In 2002, a West Virginia jury awarded $50 million in damages to Hugh Caperton, president of a mining company driven out of business after having its contract fraudulently canceled by Massey Coal Co. After the verdict but before the appeal, West Virginia held judicial elections, and Massey CEO Don Blankenship created an outside spending group and gave it $3 million in an effort to replace incumbent state Supreme Court Justice Warren McGraw with attorney Brent Benjamin, who went on to win. When Caperton's appeal came before the state's high court, the plaintiff requested Benjamin's recusal because of the justice's connection to Blankenship. But Benjamin refused to step aside and was part of the 3-2 majority that overturned the $50 million verdict.

Caperton appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 2009 ruled in Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co. that the Constitution's due process clause required Benjamin to recuse himself.

"We conclude that there is a serious risk of actual bias -- based on objective and reasonable perceptions -- when a person with a personal stake in a particular case had a significant and disproportionate influence in placing the judge on the case by raising funds or directing the judge's election campaign when the case was pending or imminent," Justice Kennedy wrote for the majority.

Now that case out of West Virginia is being cited in the ongoing legal war over North Carolina's 2011 political redistricting plan for Congress and the state legislature. Plaintiffs including the state NAACP who have filed suit over the plan say the Republican-drawn maps are unconstitutionally race-based, packing minorities into a limited number of districts and diluting their power elsewhere. And the latest battle in that war is over the recusal of a justice with substantial financial ties to the group that drew the new maps.

Last week the plaintiffs filed a motion asking N.C. Supreme Court Justice Paul Newby to recuse himself from the case because the biggest contributor to his latest re-election campaign was the Republican State Leadership Committee -- the same Washington, D.C.-based super PAC behind the redistricting plans. Thomas Hofeller, identified in the redistricting trial as the lead draftsman of North Carolina's 2011 political maps, was retained by the RSLC to draw new districts favorable to Republicans in North Carolina and other states.

Unless Newby recuses himself, the plaintiffs argue, "he will rule on the validity of redistricting plans that were drawn, endorsed, and embraced by the principal funder of a committee supporting his campaign for re-election."

This is the second time the plaintiffs have called for Newby's recusal in the redistricting lawsuit. Last November, they requested his recusal when the high court was asked to review a lower court ruling waiving attorney-client privilege between the defendants, who include the state's top legislative leaders, and their privately retained redistricting counsel. The N.C. Supreme Court denied the recusal request without explanation and went on to reverse the decision by the lower court, which ruled this past July that the redistricting maps were not unconstitutional.

The plaintiffs are now appealing that ruling to the state's high court -- and once again they are asking Newby to step aside.

Compared to the prior recusal request, they argue, "the legal principles and policy concerns requiring justice Newby's recusal in this appeal weigh even more heavily."

Big money on the high court

With Election Day approaching last fall, incumbent Newby was trailing in the polls behind Court of Appeals Judge Sam Ervin IV, grandson of U.S. Sen. Sam Ervin, famous for presiding over the Watergate hearings. Though North Carolina judicial races are officially nonpartisan, Newby is a registered Republican and Ervin is a Democrat.

With Newby poised to lose and a matter related to the redistricting suit before the state Supreme Court, RSLC poured nearly $1.2 million into a super PAC called Justice for All NC, which in turn provided nearly $1.5 million to another super PAC called the NC Judicial Coalition that spent over $1.9 million from Oct. 11, 2012 through Nov. 5, 2012 on TV ads supporting Newby. In comparison, the total amount of independent expenditures supporting Ervin was about $300,000.

The $1.2 million the RSLC contributed to Justice for All represented 79 percent of the $1.5 million Justice for All gave to the Judicial Coalition in support of Newby. At the same time, the $1.5 million from Justice for All amounted to 76 percent of the total $1.9 million that the Judicial Coalition spent on pro-Newby ads.

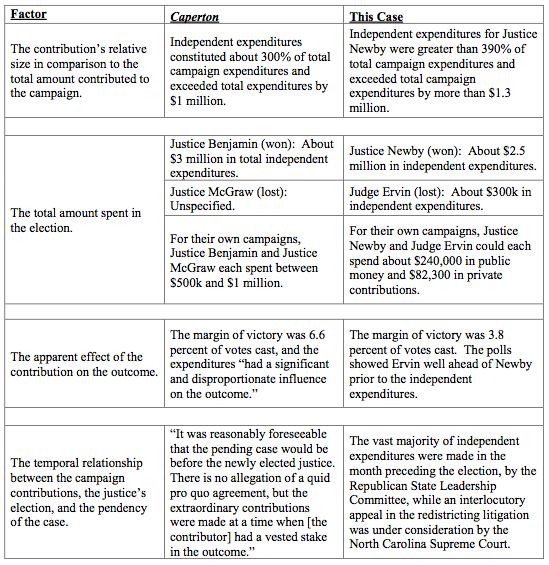

"The facts in this case are substantially similar to, and in fact more extreme, than those in Caperton," the plaintiffs note in their motion.

They even included a table comparing the facts in Caperton to those in the North Carolina redistricting lawsuit (click on chart for a larger version):

The plaintiffs point out that two former N.C. Supreme Court Justices -- James Exum, a Democrat, and I. Beverly Lake Jr., a Republican -- submitted a friend-of-the-court brief in Caperton in which they wrote:

"Substantial financial support of a judicial candidate -- whether contributions to the judge's campaign committee or independent expenditures -- can influence a judge's future decisions, both consciously and unconsciously. [We] believe that the only way to preserve a litigant's due process right to adjudication before an impartial judge is to require that a judge recuse from a case not only when the judge consciously perceives the judge's own partiality, but also when there exists a reasonable appearance of partiality or impropriety."

Besides citing the U.S. and state constitutions, the plaintiffs also argue for Newby's recusal by citing the N.C. Code of Judicial Conduct, which says a judge should recuse himself when his "impartiality may reasonably be questioned." And there is precedent for recusal, as two justices stepped aside in an earlier redistricting case that came before the N.C. Supreme Court in 2003.

But as N.C. Policy Watch has pointed out, what happens next remains somewhat of a mystery. That's because there is no formal procedure for handling such recusal requests and no requirements for oral arguments or a written opinion.

In effect, the judges will be allowed to judge themselves outside of public view.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.