The tricky business of measuring progress eight years after Hurricane Katrina

Define "progress."

For those in government, it typically means economic growth and improvements in quality of life that boost confidence among wealthy investors. Whether it has bond ratings or developers of new homes and businesses in mind, city government wants to send the message that investing there is a safe bet that will yield returns.

That's certainly the case in New Orleans, which suffered near decimation when Hurricane Katrina blew through and the federal levees broke eight years ago this week. In its attempt to bounce back, the city has sought to expand its tax base and make companies feel comfortable setting up shop there.

But the people of New Orleans have a different definition of progress, one that's rooted not in returns on investments but whether they can return to the city at all.

"If another storm came, are poor people still as dependent on others to move them out of harm's way as before the storm?" asks Andre Perry, an education equity advocate who moved to New Orleans in 2004. He is now dean of urban education at Davenport University in Grand Rapids, Mich., but he spent over 10 years in New Orleans exploring the answer to that question, which he says today is "yes."

For many across the Gulf Coast, progress can't be defined without analyzing safety for those who've been cast to the margins of society. There are two New Orleans, says Deon Haywood, executive director of Women With a Vision, an advocacy group for sex worker rights, drug policy reform, reproductive justice, and people with HIV.

"The city is rebuilding and it's making a comeback," says Haywood. "There's a new medical district, new schools, new businesses, new hip and happening areas, new housing options, and more technology. But in the other New Orleans, the poverty rate is the same as it was in 1999, the HIV rates are higher, the sheriff is building a larger jail, and adult education is at an all time low. Oh, and bicycle lanes are growing."

That about sums it up. A new medical district is in the works, but it comes at the expense of the closing of Charity Hospital, which served low-income families across the metropolitan area. There are plenty of new businesses, and the majority of public housing projects have been replaced with modern mixed-income developments.

People of color can rejoice that their share of businesses has risen in the city even as their population has dropped since Katrina. There are 34 arts and culture nonprofits for every 100,000 people in the region, which is more than double the national rate. And Haywood is indeed correct about the bike lanes: 56.2 miles worth across the city compared to 10.7 miles in 2004.

But unemployment rates have risen for black men, only 53 percent of whom are employed in the New Orleans metro area compared to 61 percent in comparable cities. There has been no increase in the region's percentage of African-American men with bachelor degrees since 1990.

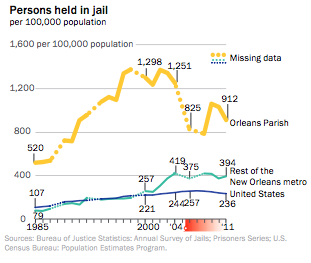

Meanwhile, Louisiana remains the incarceration capital of the world, and New Orleans, which is building a new jail, is a huge driver of that. This is true even though violent and property crime rates in the city are lower than before Katrina.

Rebuilding new homes, businesses, schools and hospitals since Katrina has led to a boost in construction industry jobs, which hasn't quite slowed, but all other industries in the area now have fewer jobs. If any economic progress has been made, it's mostly benefited white households, which have a 50 percent earning advantage over black households.

For those fortunate to have jobs, it’s been more difficult to get to work if you rely on public transit. In 2000, the percentage of New Orleans workers who used transit was 13.2 percent. In 2011, it was 7.8 percent. Recent cuts to funding for the city's ferry service may have exacerbated that, if not for last-second solutions that still need to be implemented.

To top it all off, it's getting harder just to breathe in the city: From 2010 to 2012, the metro experienced nearly double the number of "unhealthy" air quality days as Houston, which has improved its air quality while maintaining an industrial base similar to New Orleans'.

"The question is not whether New Orleans will come back or not, New Orleans will be rebuilt," says Stephen Bradberry, executive director of The Alliance Institute, who lived in the city from 1987 to 2012. "The question is who will get to enjoy the 'new' New Orleans, and eight years out we see the results."

There's a similar message in the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center's report, "The New Orleans Index at Eight: Measuring Greater New Orleans' Progress Toward Prosperity," where the above stats come from. "To be sure," the report states, "all the progress the New Orleans metro makes in other arenas will not be enough to signal to the world the emergence of a qualitatively different place post-Katrina if large segments of the population continue to be left behind."

One area often pointed to as a measure of positive growth is the status of the schools. Of students attending New Orleans Parish schools during 2012-13, 63 percent were enrolled in those that met state standards -- a huge increase from pre-Katrina, when that figure was as low as 30 percent.

But those numbers don't tell much, says Perry, who helped run charter schools while he was there.

"We have to be careful how we measure progress," he says. "The recent gains on standardized tests in education are encouraging. However, we should not equate test score growth to real human capital gains. Unemployment, college graduation rates and health outcomes are still too woeful to claim success."

The talk about progress in the city has overlooked too many New Orleanians who are frustrated with the lack of economic opportunities, says Rosana Cruz, associate director of Voice of the Ex-Offender.

"I like theaters, bike lanes and food trucks as much as the next guy, but ultimately this so-called progress is at the expense of those who are left out and left behind," says Cruz. "Many people have made money off of the rebuilding of the city, but not those who lost the most after the levees burst. These are the people who can't get jobs because they got sucked up on minor charges in our city's vacuum-like approach to crime, or because they are competing for jobs and housing with college transplants, even though they are the ones with the knowledge and experience to address the problems [on which] we haven't made progress."

It's not necessarily a bad thing that people are moving in from other areas to help rebuild New Orleans. But some newcomers are coming not only with their own definitions of progress but their own definition of what New Orleans is as a city.

"It looks to me that Black folks weren't the only ones singing along to Sam Cooke's song, 'A Change Is Gonna Come,'" says Bradberry. "The only difference is that the power elite of New Orleans is hell-bent on making their vision a reality, while low-income and African American families in New Orleans languish in stunned disbelief of the inhumanity of it all."

Says Cruz, "We are losing the soul of the city because people want to look at progress and not remember, preserve and take responsibility for what we're losing."