Fracking chemical disclosure divides North Carolina officials

Requiring public disclosure of chemicals used in fracking for oil and natural gas has proven to be a controversial issue in the states -- and in North Carolina the issue has pitted a regulatory commission against the state lawmakers who created it.

Last week the N.C. Mining and Energy Commission (MEC) voted unanimously to protest the state Senate's effort to take away its authority to set rules about fracking chemical disclosure. The legislature set up the commission last year after voting to allow fracking in the state and charged it with creating an oil and gas regulatory program.

The MEC had pledged to craft the nation's strictest rule for disclosure of fracking fluids, which include toxic chemicals such as ethylene glycol, methanol and naphthalene. But state Senators are attempting an end run around the commission with a revised version of a bill that the House passed in May. Last week the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources overwhelmingly approved revisions to House Bill 94 that would allow oil and gas companies to designate chemicals as "trade secrets" and require their public disclosure only in cases where the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) issues a written declaration that a situation endangers public health or the environment.

The News & Observer reported that DENR requested the changes over concerns that it didn't want to be a repository for corporate trade secrets. Under the revised legislation, property owners affected by fracking could challenge companies' trade-secret claims in N.C. Business Court, which specializes in complex issues of corporate law.

Following heated debate over the Senate's move, the MEC agreed to send a memo protesting the change to Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger and House Speaker Thom Tillis, both Republicans. The June 30 memo by MEC Chair James Womack -- who is also a Republican county commissioner in rural Lee County, in the state's fracking zone -- notes that the MEC "committed several months of effort" in researching and analyzing other federal and state regulations in developing its draft rule, which was vetted by the MEC's stakeholder group that includes industry representatives, and objects to the wording of H94:

As written, the language would allow any company to claim exemption from disclosure of important information about potentially dangerous hydraulic fracturing fluids being pumped into oil and gas wells, denying knowledge of those chemicals to state officials without any effort to verify the validity of the trade secret.

Womack's memo also criticizes the politics of the Senate's move, accusing it of handing ammunition to fracking's critics:

Media and environmental interest group reactions to the proposed new language were immediate and sharply critical. This one simple change has reinvigorated anti-drilling fervor across the state; an outcome the MEC has worked tirelessly to avoid.

An outspoken advocate of fracking, Womack was appointed to the commission by Berger.

During the MEC's discussion of the Senate legislation, some commissioners expressed concerns about energy companies privately negotiating fracking standards with lawmakers rather than bringing their issues to the commission. Among the companies reportedly involved in the behind-the-scenes negotiations is oilfield services giant Halliburton, a fracking pioneer with headquarters in Houston. Earlier this year, Halliburton blocked the MEC from adopting a strict disclosure rule, complaining to DENR that it went too far.

Fracking -- shorthand for hydraulic fracturing -- involves blasting large amounts of water and chemicals into shale rock formations at high pressure to break them apart and release natural gas or oil. Reports of drinking water wells in the United States being contaminated with chemicals from nearby fracking operations go back at least as far as the mid-1980s, to a case involving a residential well in West Virginia.

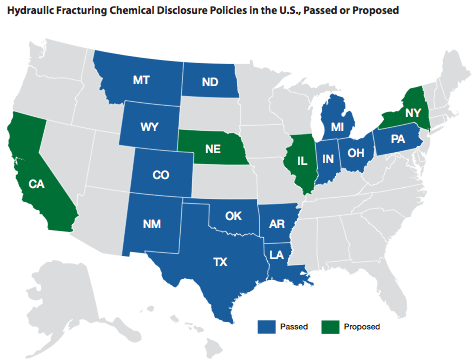

If the MEC prevails over the Senate and adopts strict fracking chemical disclosure rules, North Carolina would be an outlier among Southern states where fracking is underway.

OMB Watch, a nonprofit now known as the Center for Effective Government that promotes transparency, released a report last year that found most of the states where fracking is taking place and that do not require any public disclosure of the chemicals used are in the South. It also found that Southern states are among those with the weakest disclosure laws.

Of the seven states with significant gas drilling activity that don't require any public disclosure of chemicals, five are in the South: Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Virginia and West Virginia. The others are Kansas and Utah. And among the 17 states with weak disclosure requirements, three are in the South: Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas.

In 2005, Congress exempted the oil and gas industry from having to disclose chemicals used in fracking, leaving regulation largely up to the states. In May, the U.S. Interior Department adopted rules requiring disclosure of chemicals used in fracking on public lands, but environmental advocates criticized the requirements as being too weak to adequately protect the public.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.