Who are the 'undocuqueer'? New reports shed light

By Elena Shore, New America Media

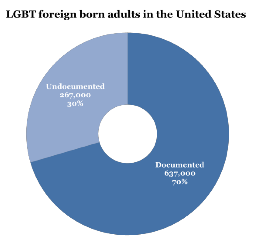

A report released last week by the Williams Institute at UCLA estimates that there are at least 267,000 self-identified LGBT undocumented immigrant adults living in the United States. The number is a conservative estimate -- because many people who fit into both categories are reluctant to identify as such; and because it doesn't include anyone under the age of 18. Another 637,000 self-identified LGBT individuals are estimated to be among the adult documented immigrant population.

The report, based on data from the Pew Hispanic Research Center, Gallup Daily Tracking Survey and the Census Bureau's American Community Survey, is the first-ever study to estimate the number of LGBT undocumented immigrants in the country. The findings were presented in Washington, D.C. at a press briefing organized by the think tank Center for American Progress, which released its own report analyzing the policy implications of the numbers.

"Sexual minorities and undocumented are two groups about which we don't have much quality data," noted Williams Distinguished Scholar Dr. Gary Gates, who directed the study.

Yet LGBT undocumented immigrants -- or "undocuqueer" as many refer to themselves -- have played a prominent role in the immigration reform movement, especially among DREAMers, young undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children.

"This is one of the most under-reported stories" in the immigration reform movement, noted José Antonio Vargas, the Filipino American Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who announced publicly that he was undocumented in 2011. "The undocumented youth movement is led by queer people."

The estimate released today may be conservative, Gates said, but it is useful in documenting this segment of the population.

"As we know with numbers, it hides as much as it reveals," added Vargas. "Just looking at my Facebook page and my Twitter account, I can tell you it's a bigger number than this."

When he told his family he was gay, Vargas said his grandfather kicked him out of the house -- partly because his grandfather was conservative, and partly because, as Vargas said, he had ruined "the plan," which was "to come to America, marry a woman and get my papers that way."

But applying for a green card through marriage is an avenue that is not open to same-sex couples.

That's because same-sex marriage is not recognized at the federal level. Even if a same-sex couple is legally married in one of the nine states (or the District of Columbia) that allows same-sex marriage, the federal Defense of Marriage Act prevents them from accessing many of the benefits other couples receive, including the right to apply for a green card through a U.S.-citizen spouse.

The ripple effect of this has very real economic consequences for same-sex couples, according to attorney Michael Jarecki.

When it comes to employment, noncitizen spouses are at the mercy of their employers -- when a job ends, so does their work visa.

Same-sex families who are enrolling a foreign national child in school must pay out-of-state tuition, which can put strains on their finances.

Many same-sex couples have children, according to the Williams Institute report. Of the 25,000 binational same-sex couples in the country, one in four has children. And of the more than 11,000 couples where both partners are non-citizens, nearly half of them are raising kids.

"It's not just a couple being forced to split up," if, for example, an undocumented spouse is detained or deported, explained Gates. "It's an entire family."

Some of the hurdles all immigrants face are magnified for LGBT individuals.

For those seeking asylum in the United States, there is a one-year deadline during which they have to file their claim -- a limitation that Jarecki says "disproportionately" affects LGBT individuals because the coming out process may take longer than a year.

LGBT individuals in detention suffer sexual violence and often don't have a place to report it. Transgender individuals who are detained in separate cells, supposedly for their "protection" from the other detainees, are essentially in solitary confinement.

As Congress moves toward a plan for comprehensive immigration reform, advocates for the rights of LGBT immigrants hope that any reform bill will include protections for LGBT individuals, couples and families. These include ending discrimination against binational same-sex couples, repealing the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and modifying detention and asylum standards to address the issues faced by LGBT undocumented immigrants.

But Vargas warned that not enough is being done when it comes to LGBT and immigrant rights advocates working together.

For example, Vargas said, he had thought the LGBT community would have embraced immigration reform as their issue. "I've been rather surprised," he said. "I feel like the LGBT advocacy community here in D.C. needs to step up on this."

"The LGBT community's relationship with immigration reform has been a complicated one," explained Maya Rupert, policy director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, one of the groups that has been active on the issue of immigration reform.

LGBT immigrants are often most visible as same-sex couples or DREAMers, she noted. "Very often, we see this attempt to divide and say there are deserving, good immigrants and there are bad or guilty ones."

Any negative messages directed at undocumented immigrants may not be targeting LGBT immigrants now, she said, but they could easily become a target in the future.

"We need to combat those types of messages wherever we see them…and advocate for the kind of world we want to live in," said Rupert.

"The country will only get gayer [because more people are coming out], it will only get browner, it will only get more Asian," said Vargas.

Gates of the Williams Institute agreed, saying people under 30 are twice as likely to identify as LGBT. "That population," he explained, "is growing up in a world more comfortable with self identifying."

"If I were a senator looking at comprehensive immigration reform [and whether to include protections for LGBT immigrants]," added Vargas, "I'd have to ask, 'What side do I want to be on?'"