The reality of the U.S. violence epidemic beyond Sandy Hook

Friday's massacre of 20 first-grade students and six adults at the Sandy Hook elementary school in Newtown, Conn. by a disturbed young man who also killed his mother has sparked a conversation about what needs to happen to prevent these shockingly common mass shootings in the United States.

Speaking Sunday night at an interfaith prayer service for the victims, President Obama said the nation is "left with some hard questions":

This is our first task -- caring for our children. It's our first job. If we don't get that right, we don't get anything right. That's how, as a society, we will be judged.

And by that measure, can we truly say, as a nation, that we are meeting our obligations? Can we honestly say that we're doing enough to keep our children -- all of them -- safe from harm? Can we claim, as a nation, that we're all together there, letting them know that they are loved, and teaching them to love in return? Can we say that we're truly doing enough to give all the children of this country the chance they deserve to live out their lives in happiness and with purpose?

I've been reflecting on this the last few days, and if we're honest with ourselves, the answer is no. We're not doing enough. And we will have to change.

Obama went on to note that the occasion marked the fourth time the nation has confronted the horror of a mass shooting since he was president. Mother Jones has tallied up the numbers and reports that since 1982 there have been at least 62 mass murders carried out with firearms in 30 states across the United States. California was the state with the most mass murders, at eight, followed by Florida and Texas with four each.

These mass shootings focus the attention of the national public, press and politicians. But do the family and friends of victims of individual murders suffer any less than the loved ones of those killed en masse?

These mass shootings take place in a broader context of violence that also needs to be understood and addressed if we're serious about caring for the nation's children. The fact is, the United States is an unusually violent nation -- and the South is its most violent region. Most victims of the U.S. violence epidemic do not look like those in Newtown, a New England community that is 95 percent white with a median household income over $90,000.

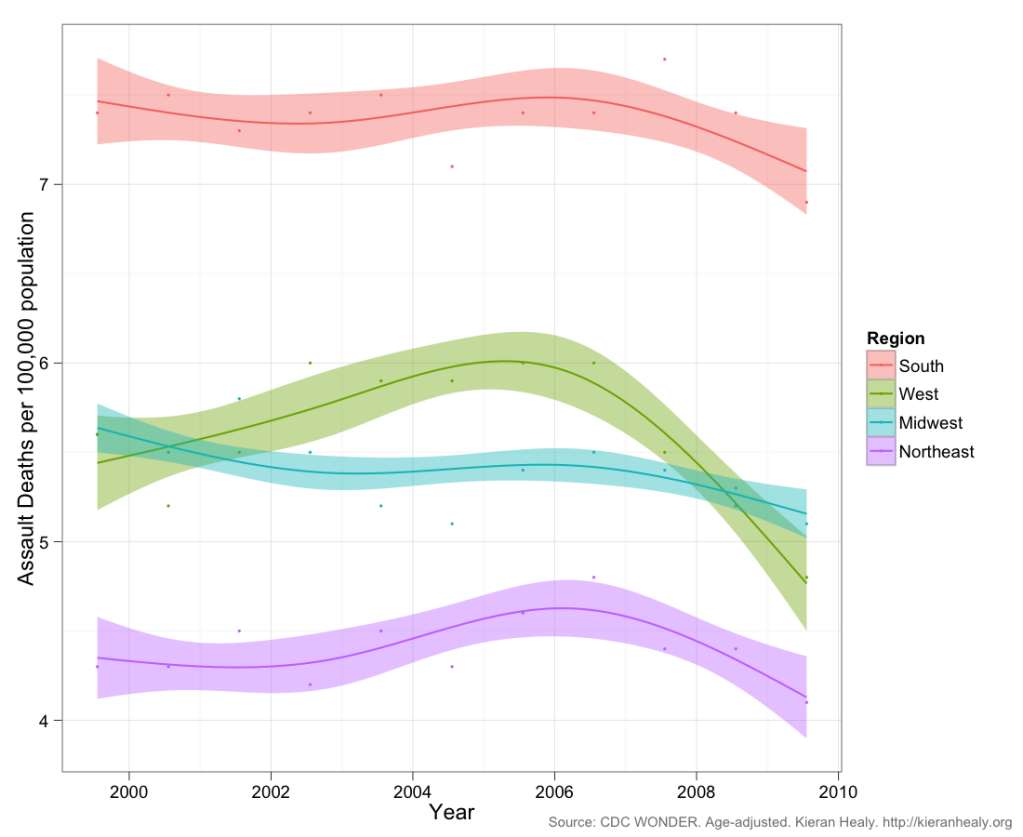

Kieran Healy, a sociology professor at Duke University in Durham, N.C., has extensively analyzed assault deaths, finding that the U.S. is much more violent than the 33 other developed nations that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development -- and the South has a violence problem far greater than the rest of the country:

Of the 15 U.S. states with the highest murder rates, eight are in the South: Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, Arkansas and North Carolina. Looking at the data for 2011, Louisiana has the highest murder rate by far, with 11.2 murders per 100,000 people. It's followed by Mississippi with 8 murders per 100,000 people, while South Carolina is tied with Maryland for fourth place with 6.8 per 100,000.

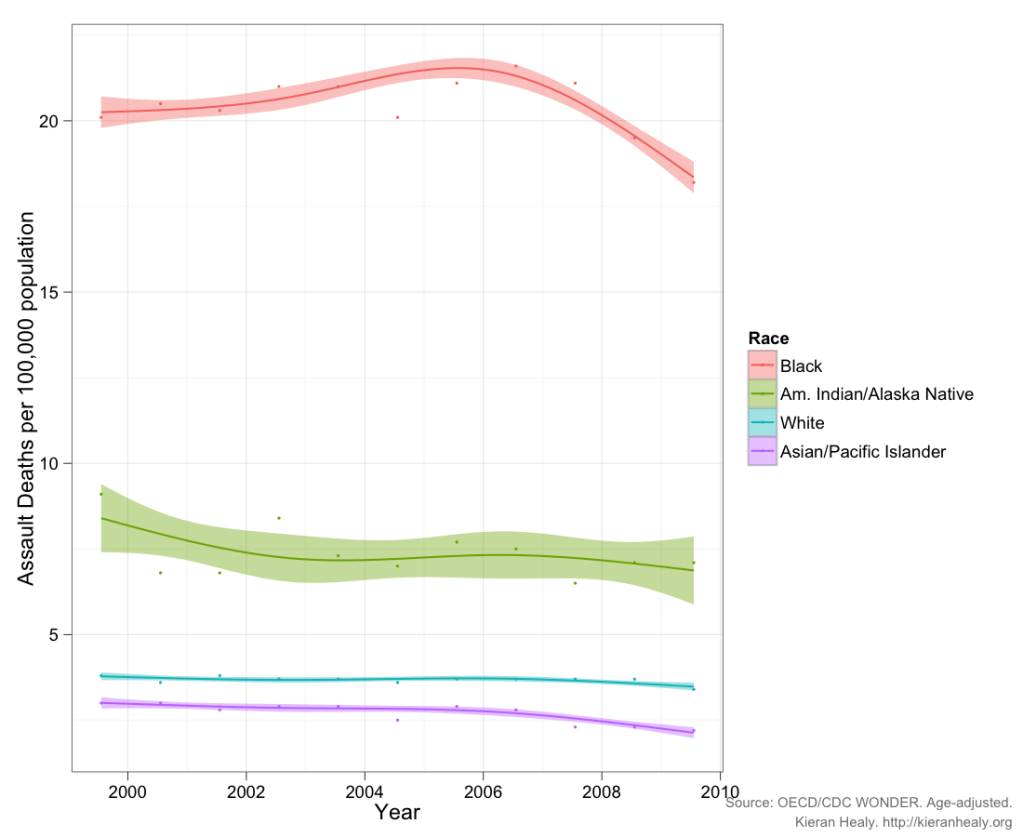

Healy's research has also shown that African Americans are far more likely to be the victims of deadly assaults than people of other races:

As Healy writes:

The story here is depressing. Blacks die from assault at more than three times the U.S. average, and between ten and twenty times OECD rates. In the 2000s the average rate of death from assault in the U.S. was about 5.7 per 100,000 but for whites it was 3.6 and for blacks it was over 20.

Though Healy does not point this out in his analysis, homicide rates tend to increase with poverty. So is it any surprise that African Americans, whose poverty rate is triple that of non-Hispanic whites, also disproportionately suffer from violence? Or that the South, a region that has long struggled with entrenched poverty, is the most violent U.S. region?

While the victims of most of these assaults are not children, the incidents still have a devastating impact on young people through the damage they do to families and communities. If the president and the nation are serious about caring for children, deadly violence in its more common forms must also be addressed.

In the aftermath of the Sandy Hook tragedy, there are growing calls for stricter gun control laws. They have come from the usual quarters, including gun-control advocacy groups, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.). But there are also new voices speaking up on the issue, like U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), an avid hunter and longtime defender of gun rights who received an "A" rating from the National Rifle Association. Speaking today on the MSNBC program "Morning Joe," Manchin said he supported re-evaluating laws that allow people to own assault rifles and clips that hold dozens of rounds of ammunition.

There are also mounting calls to address the U.S. mental health care crisis. Outgoing U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), who is calling for a commission to look at the problem of gun violence and its causes, echoed the opinion of many by saying we need to consider ways to better help "people in trouble, mentally." Sandy Hook shooter Adam Lanza was said by relatives to have suffered from a personality disorder and had reportedly been diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome, while his mother was allegedly stockpiling guns and food to prepare for a possible economic collapse, raising questions about her own mental state.

Perhaps Sandy Point will be a turning point for addressing the nation's epidemic of deadly violence. But given that the problem tends to disproportionately affect the nation's poorest people, families, communities and region, let's hope that the structural issues that lead to such violence also get the attention they demand.

(For a larger version of the map by tablemtn, which is based on 2009 FBI data, click here.)

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.