Marco Rubio's DREAM Act: The new 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'?

By Elena Shore, New America Media

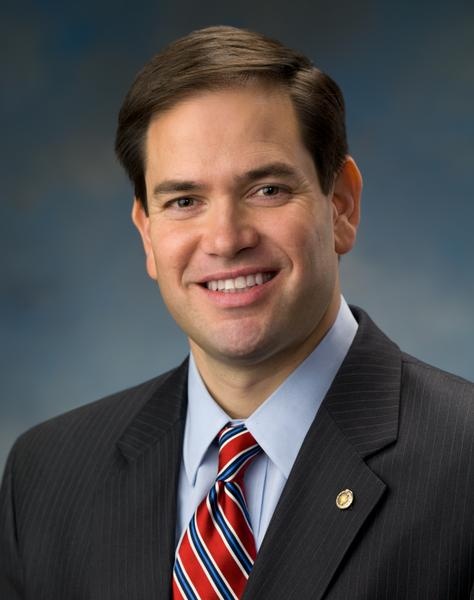

Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio on Wednesday dismissed speculation that he could be the vice presidential nominee, but he is preparing to make another political play: He is about to release his version of the DREAM Act -- one that would offer legal status without a pathway to citizenship for undocumented students.

The move could be a game changer in immigration politics.

The federal DREAM Act, which would have provided a path to citizenship for undocumented high school graduates who were enrolled in college or the military and met certain requirements, originally enjoyed bipartisan support.

But things have changed.

Republicans blocked the bill when it last came up for a vote in December 2010. Republican David Rivera has put forward a military-only version of the DREAM Act, called the ARMS Act. Mitt Romney says he would veto the DREAM Act if he is elected president.

Now Sen. Rubio, a Cuban American who says he opposes the DREAM Act, is about to release his own version of the bill. But his stance on immigration has not gained the Florida senator widespread popularity among Latinos in the rest of the country.

If the bill gains traction in Congress, it would be a coup for the GOP -- a party that has been shifting further to the right to appease a sector of nativist conservatives, with mainstream candidates like Romney publicly espousing anti-immigrant views.

If they are able to pull it off, Republicans would be able to do what no Democrat could do -- a la Nixon in China -- going down in history as the party that moved immigration reform forward (even if it is piecemeal) and simultaneously rebooting their chances with Latino voters in the 2012 presidential election.

But Rubio's version of the DREAM Act is no dream; a New York Times editorial called it "A Dream Act Without the Dream."

It is more like the 2012 version of former Pres. Bill Clinton's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy -- a move that at the time was seen as a step forward (after all, it was better than an explicit ban on LGBT people in the military), but ultimately created a second-class citizen status for LGBT military personnel, not equal rights.

Like "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," Rubio's version of the DREAM Act may be better than nothing -- but by denying a path to citizenship to undocumented students, it traps them in a legal category as a kind of second-class citizen (or, more accurately, non-citizen).

Immigrant rights advocates are now taking the temperature of the political landscape to determine what the bill's chances are of gaining traction in Congress. They will have to decide whether to back the bill, as what could be the only viable option to improve the legal status of undocumented students here (that is, if it succeeds in gaining bipartisan support); or to hold out for the original version of the bill that would offer a path to citizenship and real equality (even if it has lost its momentum).

Like LGBT activists in 1993, immigrant rights advocates today are facing a Catch-22, where taking a step toward equality simultaneously would cement their status as "second-class citizens."

In fact, the similarities between the two movements go even further.

In "coming out" as undocumented, DREAMers -- undocumented students who support the DREAM Act -- took a page from the LGBT rights movement. Well-known DREAM activists like Jose Antonio Vargas and Gaby Pacheco are in some ways continuing in the tradition of Harvey Milk, who saw coming out as a political act.

It also happens that "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" was repealed on the same day the DREAM Act died in the Senate, Dec. 18, 2010. The day was "bittersweet" for some DREAM activists, many of whom are LGBT themselves or are allies of the movement and had hoped that both votes would go their way.

For both movements, the politics are personal.

And both face staunch opposition that has managed to get referendums on the ballot in various states. In Maryland, for example, one referendum likely to appear on the November ballot would overturn Maryland's recently-passed marriage equality bill; another would overturn the Maryland Dream Act that allows some undocumented students to qualify for in-state tuition.

Meanwhile, as lawmakers introduce their own versions of the federal DREAM Act -- a blatant political move in an election year -- it's unclear what will happen to the real people affected by these policies: undocumented students who have no means of working legally after they graduate from college.

It seems that for now, the way forward for immigration advocates could be a dark tunnel.