Dr. King's march to Occupy D.C. for economic justice

On December 4, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. announced that he was launching the "second phase" in the civil rights struggle: A Poor People's Campaign that would unite the poor and working class across racial lines to win full employment, affordable housing and other economic justice demands.

Dr. King and his allies knew they needed a bold and dramatic event to kick off the campaign and push poverty into the national consciousness. The strategy they landed on will be familiar for activists of today: A full-scale occupation of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Here's how Dr. King described his vision:

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference will lead waves of the nation's poor and disinherited to Washington, D.C. next spring to demand redress of their grievances by the United States government and to secure at least jobs or income for all. We will go there, we will demand to be heard and we will stay until America responds. If this means forcible repression of our movement, we will confront it, for we have done this before. If this means scorn or ridicule, we embrace it, for that is what America's poor now receive. If it means jail, we accept it willingly, for the millions of poor already are imprisoned by exploitation and discrimination.

In the spring of 1968, Dr. King criss-crossed the South and country rallying support for the march and its chief policy demand, for Congress to pass an Economic Bill of Rights. He pledged the occupation would be non-violent, but militant: The goal was to disrupt business as usual in the nation's capitol until politicians and the nation got serious about addressing economic justice.

King's leadership in the campaign was cut short in April, when he was murdered at a rally supporting striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. But plans for the D.C. occupation continued under King's chosen successor, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who was thrust into leading the demonstration in May 1968.

On Mothers' Day, May 13, Coretta Scott King led thousands of women in a march that included Ethel Kennedy, the wife of then-presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, who would be assassinated just weeks later.

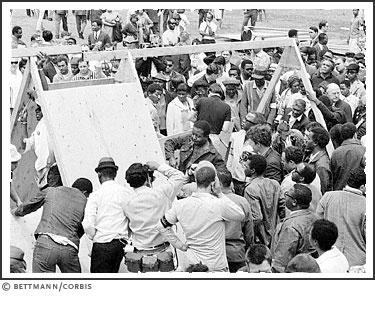

The next day, the protesters erected tents and shacks, what they labeled a "Resurrection City." The occupiers made regular visits to federal agencies demanding action. But the occupation was doomed: After six weeks of relentless rain and media indifference, Resurrection City was closed and the campaign called off.

What would Dr. King have thought of today's occupations for economic justice? There's little doubt he'd embrace the tactic of taking over public space and engaging in civil disobedience to highlight inequality. After the SCLC's struggle to keep the momentum going in his absence, Dr. King may even appreciate Occupy's horizontal decision-making aimed at making it less dependent on individual leaders.

Dr. King envisioned a movement more directly rooted among those most severely affected by the intersections of racism and inequality, particularly poor African-Americans in the South. For better or worse, he also saw the need for a clearer policy agenda -- in his case, the Economic Bill of Rights, an idea that started with President Roosevelt in 1944.

There's no question that the issues Dr. King occupation march was raising are still relevant. As a new report by United for a Fair Economy notes, the racial wealth gap remains a "national embarrassment." In 2010, poverty rates among Blacks (25.7%) and Latinos (25.4%) were more than two and a half times the white poverty rate, and unemployment stands at 7.5 percent for Whites, 15.8 percent for Blacks and 11 percent for Latinos.

At this rate, the report concludes, by 2042 Blacks and Latinos will both have lost ground in average wealth, holding only 19 cents and 25 cents for each dollar of white wealth. This economic chasm, the group argues, will be exacerbated by such racial injustices as inequality in schools and incarceration rates.

Whatever changes in policy come from Occupy's actions, it's likely to have the same effect that Dr. King's march and Resurrection City had on an earlier generation of activists. As historian Gordan Mantler wrote of the 1968 occupiers:

Whether they went for months, weeks, or just a day or two, many marchers left Washington enlightened, if not transformed.

PHOTO: Activists erecting a shanty at the Poor People's Campaign encampment on the National Mall in D.C., May 14, 1968

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.