Are undocumented immigrants 'persons'?

When the U.S. Census counts the population of the country every 10 years, who qualifies as a person? This week, the state of Louisiana filed a lawsuit which challenges the Census' long-standing policy of counting all residents -- citizens and non-citizens -- and using those results to divide up seats in the U.S. Congress.

The lawsuit, which has broad implications for the political role of immigrants, comes after Louisiana lost a Congressional seat following the 2010 Census count. Thanks to the massive displacement after Hurricane Katrina -- the city of New Orleans lost 30% of its population between 2000 and 2010 -- Louisiana's delegation fell from seven seats to six.

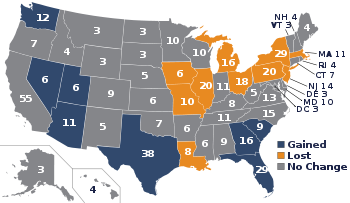

During the last 10 years, every other Southern state saw growth -- in many cases fueled by new immigrants. Texas, for example, gained four Congressional seats thanks to its burgeoning population; the Census estimates two-thirds of the growth came in the Latino/Hispanic community.

New immigrants were also key to increases in size, and added Congressional seats, in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. Nationally, about 22% of voting-age Latinos are not citizens.

In the lawsuit filed directly to the Supreme Court, Louisiana v. Bryson [pdf], Louisiana argues that the Census policy of counting non-citizens allows other states to gain clout "at the expense of states containing relatively few" undocumented immigrants, like Louisiana. Leave out the undocumented residents, Louisiana says, and it would still have seven Congressional seats.

Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell innocently says that "Louisiana's complaint simply asks the court to require the federal government to re-calculate the 2010 apportionment of U.S. House of Representatives seats based on legal residents."

If the Supreme Court ruled in Louisiana's favor, the fallout would be anything but simple. Aside from forcing 17 states to scrap their political maps on the eve of the 2012 elections, the law would fundamentally change how the Census works and immigrants are recognized in the country.

The U.S. Constitution originally said the Census should involve "counting the whole number of free persons," which the 14th Amendment changed to "counting the whole number of persons," including non-citizens.

Changing that mandate would be felt at every level of government and the economy. States and localities, which provide services like police, fire and medical treatment to undocumented residents, depend on billions in federal aid based on whole-person counts. Undocumented residents also paid $11.2 billion in taxes in 2010.

If the Supreme Court sided with Louisiana in saying that undocumented residents shouldn't count in divvying up Congresional districts, they may be cornered into saying the Census can't count them for other policy matters as well.

This isn't the first time Louisiana leaders have dragged the Census into the immigration debates roiling the South and country. In 2009, U.S. Sen. David Vitter (R-LA) introduced an amendment to the bill funding the 2010 Census that would have required Census workers to ask residents if they were U.S. Citizens; the senate voted down the measure.

Redistricting advocate Justin Levitt, who runs the website All About Redistricting, said on Twitter that the Louisiana suit "will lose, and lose badly, for several reasons." Rick Hasen at the University of California-Irvine agrees on the Election Law Blog:

How appealing will be an argument to a bunch of originalists/textualists that the term “persons” in the Constitution does not include all people, and in fact excludes non-legal residents?

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.