Sick for Justice: BP Deepwater Horizon Spill

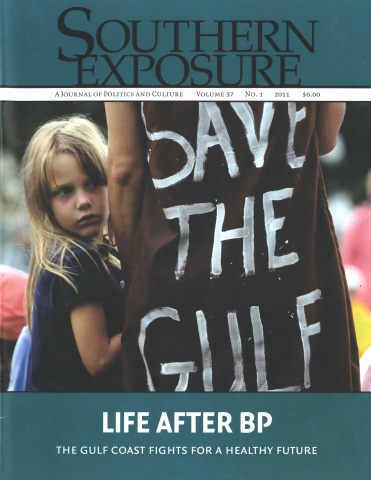

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 37 No. 1, "Life After BP." Find more from that issue here.

When BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010, the disaster upended Cherri Foytlin’s life, pushing the 38-year-old mother of six on a path of activism she had never imagined.

At the time, the Foytlins were just getting back on their feet after losing their home in Oklahoma to foreclosure. Foytlin’s husband, an oil industry worker, moved the family to Louisiana to find a better job, and they ended up in Rayne, a town 150 miles west of New Orleans. Her husband was hired as a service technician for offshore rigs, and Foytlin also found work as a reporter for a small-town newspaper.

“We were doing pretty good,” Foytlin says.

So good that they even managed to buy a new house. But three days after the sale, the Obama administration called for a six-month moratorium on new deepwater projects until they could be proved safe—and Foytlin’s husband was shifted from his offshore job to a lower-paying position in his company’s shop. They fell behind on their mortgage and were forced to use food stamps.

But Foytlin wasn’t just worried about money: She also feared that stories of people affected by the spill weren’t being told. She began visiting Gulf communities where pollution was washing ashore; when she came home she suffered severe headaches and respiratory problems.

“It felt like I was breathing with only a small piece of my lungs,” she says.

Her doctor diagnosed her with severe bronchitis, telling her it was one of the worst cases he had ever seen. But when she asked him to do tests to see if it was linked to chemical exposures, he refused to perform them.

That led her to the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), a leading grassroots group in south Louisiana that agreed to do some tests. They discovered Foytlin’s blood levels of ethylbenzene, a toxic chemical found in petroleum, were three times the national average. Ethylbenzene is known to cause eye and throat irritation and damage to the inner ear; it’s also classified as a possible human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

That discovery—and the fear of her children ages 3 to 14 losing their mother too soon—turned Foytlin into an outspoken activist. She has talked to federal officials and numerous reporters about what she and other Gulf residents are experiencing.

To make sure the media noticed, in March and April 2011 Foytlin walked all the way from New Orleans to Washington, D.C., where she joined protests at a youth-led conference called Power Shift advocating for a transition to cleaner energy sources. The activists presented BP with a bill for $9.9 billion—the amount the company had initially anticipated writing off on its tax bill for the Gulf disaster. BP has since upped that amount to almost $13 billion.

For Foytlin, activism has now become a life calling. “It’s really a rescue mission for me,” she says. “I can’t see people suffer and do nothing.”

“Accidental Activists”

Foytlin’s story echoes that of many Gulf residents who have been spurred to action by the BP disaster. Rjki Ott, a marine toxicologist and former commercial fisher from Alaska who became active herself in the wake of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, describes them as “accidental activists.”

“These are people who were minding their own business when something happened to them that made them into activists,” Ott told Southern Exposure. Ott has encountered many such newly engaged residents since BP’s calamity. When the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, Ott came to the Gulf Coast to meet with concerned citizens and share lessons from the earlier disaster in Alaska.

People would often ask her what they should do. But Ott would turn the question around: What did they think should happen?

“Figuring out what to do together is the key,” says Ott, who sees the BP disaster as an opportunity to engage more Deep South residents in challenging unaccountable corporations.

Ott says many residents have asked for more independent testing to see what kind of contamination they’re being exposed to from the spill. Ott and others were able to put them in contact with LEAN, which was founded 25 years ago to address industrial pollution.

LEAN quickly responded to concerns about a lack of protective gear for cleanup workers, purchasing about $12,000 worth of equipment themselves. The group also met with federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration officials after hearing stories about cleanup workers threatened with being fired for wearing protective equipment.

At the same time, Wilma Subra—an award-winning environmental chemist who works with LEAN— took environmental samples and had them tested for oil-related contamination. She also analyzed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air monitoring data and confirmed that Gulf Coast residents were being exposed to potentially dangerous levels of airborne contaminants. She conducted independent tests that confirmed the presence of significant levels of oil pollution in coastal soils and plants as well as in sea life.

In addition, Subra has been sampling the blood of cleanup workers and coastal residents—and finding unusually high levels of contaminants associated with petroleum pollution in people’s bodies. The work she and LEAN have been doing is part of an organizing strategy to arm Gulf Coast residents with the data they need to ensure their concerns are taken seriously by regulatory authorities.

“We are gathering evidence that I don’t believe you can dismiss,” says Marylee Orr, LEAN’S executive director.

A Lifelong Fight

Carrying out their own scientific tests is just one of an array of strategies the Gulf’s grassroots groups are using to channel community anger towards long-term solutions.

There’s certainly plenty of anger: When BP claims czar Kenneth Feinberg spoke in New Orleans on the one-year anniversary of the disaster, one man spoke for many when he yelled, “We’re sick and this is what happened to us. We’ve been poisoned by BP.”

But getting heard—especially when competing with the money, lobbyists and public relations savvy of oil companies—can require some creativity.

That was the approach used by two enterprising men at the high-powered Gulf Coast Leadership Summit held in April 2011. They called an impromptu press conference, one claiming to be a federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) staffer who announced a ban on chemical dispersants, and another who said he was a spokesperson for BP, which was offering to pay for free medical clinics for those sickened by the spill.

But the men were imposters, and the press conference was actually a piece of political theater organized by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, the grassroots group based in New Orleans, with help from the Yes Lab, a project that helps activist groups get media attention in creative ways.

“This action was all about highlighting the fact that people are truly sick and the government and BP are just standing by,” says Bucket Brigade Executive Director Anne Rolfes.

After months of official silence, the agitation and persistence of Gulf activists may finally be forcing officials to address their health concerns. At the April 2011 panel discussion with Feinberg in New Orleans, U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) pledged to follow up with BP on medical claims. She also said she is planning to hold a meeting specifically to address health problems related to the spill.

And on May 24, a coalition of 154 organizations that advocate for public health, the environment and fishing communities sent a letter to EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson and HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius asking for immediate action on the Gulf health crisis. Among their demands was the creation of a Gulf Coast Health Restoration Task Force that includes members of affected communities.

“Making our communities whole again includes helping every man, woman, and child who has become and will become sick as a result of the BP oil disaster,” the letter stated. “Restoring our environment also means restoring our community’s health.”

In the meantime, Foytlin—and many other concerned Gulf Coast citizens like her—have no intention of letting up. Though she once thought her walk to Washington would be her last act as an activist, Foytlin now says she realizes that it was really only the beginning of what promises to be a much longer struggle for a healthier and safer future in the Gulf.

“We’re going to keep fighting,” says Foytlin. “This is going to be a lifelong project for me.”

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.