A Regulatory Disaster

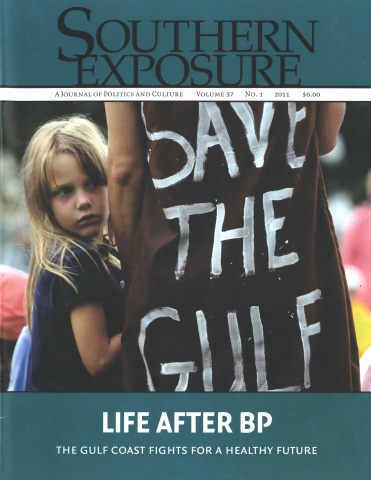

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 37 No. 1, "Life After BP." Find more from that issue here.

When BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig blew in the Gulf, Rik Ott, a marine toxicologist from Alaska, had a sinking feeling: Here we go again.

Ott was touring the United States to promote her book Not One Drop, the story of what until then had been the nation’s worst oil spill—the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, which unleashed up to 32 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

Back then, Ott was working as a commercial salmon fisher in the area. She responded by writing about the environmental and social fallout of the disaster and founding several nonprofits to help Alaskan communities deal with the impact.

When BP’s failed rig began gushing oil into the Gulf, Ott’s first instinct was to turn away. “I didn’t want to go,” Ott told Southern Exposure. “It hurt too much.”

But Ott managed to stay away for only 10 days. She quickly became convinced that many of the post-spill mistakes made in Alaska were being repeated in the Gulf—and putting the health of thousands of coastal residents in jeopardy.

Over the last year, Ott has been crisscrossing the Gulf, collecting stories from hundreds of people from Florida to Louisiana. These conversations have led her to believe there is an environmental health crisis unfolding in the Gulf that was exacerbated by the federal government’s failure to take appropriate action to protect cleanup workers and coastal residents.

“There are a lot of sick people in the Gulf, with reports of respiratory problems, skin rashes and other issues that won’t go away,” Ott says. “The federal government has done a huge disservice by pretending this isn’t a problem.”

Lessons from the Past

Exhibit A of the government’s failure to address the public health aftermath of the BP disaster, Ott and others contend, is the medical problems now afflicting many of the workers mobilized to clean up the spill. According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), about 100,000 people went through cleanup worker safety training in response to the BP disaster. Currently the agency is studying the possible impacts of the BP spill on cleanup workers.

However, that research is geared toward helping prepare for future incidents, rather than helping those who may have been harmed after the Gulf catastrophe.

The reported illnesses should have come as no surprise: People who were involved in the Exxon Valdez cleanup two decades ago reported a flu-like respiratory illness that was dubbed “Valdez Crud,” the symptoms of which—coughing, burning eyes, chest pain, etc.—are consistent with exposure to toxic chemicals found in crude oil.

Over time, many Exxon Valdez cleanup workers say they developed more chronic conditions, including memory loss and cancer, which they contend are likely consequences of long-term chemical exposure.

Though there were no published, peer-reviewed health studies of Exxon Valdez cleanup workers, an unpublished pilot study by a Yale graduate student in 2003 included a phone survey of 169 of those workers that found those with significant oil exposure or exposure to oil fumes were more likely to report symptoms of chronic airway disease than those with less exposure.

Based on such findings, Ott told Congress that as many as 3,000 former Exxon Valdez cleanup workers suffer from spill-related health problems.

More recently, a study by Spanish scientists published last August in the Annals of Internal Medicine looking at fishermen who responded to a 2002 spill of 20 million gallons of oil from a tanker off the northwestern coast of Spain found that participation in the cleanup was associated with persistent respiratory problems such as coughing and shortness of breath.

The Spanish cleanup workers also showed chromosomal abnormalities in their white blood cells that increased with intensity of exposure.

These kinds of effects are just what public health experts would expect. One of the key components of crude oil, for example, is benzene, which the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, say causes damage to the blood, immune system and reproductive organs, and can lead to leukemia.

Lacking a Plan

Given what’s known about the potential health impacts on cleanup workers, BP and federal officials seemed unprepared to address these threats in the face of the largest oil spill in history.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the federal agency in charge of protecting workers from on-the-job hazards, deployed personnel to the Gulf the week after the rig exploded. But even at the height of the cleanup effort, the cash-strapped agency had at most only 50 personnel assigned solely to the oil cleanup—far too few to comprehensively monitor a massive effort that stretched from Texas to Florida.

OSHA also worked with the National Institute on Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to establish rules regarding protective equipment and training for cleanup workers. But those rules were not always followed.

In July 2010, for example, OSHA officials sounded an alarm over shortcuts in the required 40-hour training for cleanup supervisors.

“We have received reports that some are offering this training in significantly less than 40 hours, showing video presentations and offering only limited instruction,” U.S. Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health, Dr. David Michaels, announced last July.

Officials may also have been handcuffed by limitations in federal law. In 2010, the Center for Progressive Reform (CPR), a nonprofit watchdog group in Washington, D.C., released a report documenting the way the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 limits the role of agencies like OSHA and NIOSH in the oil spill planning process.

Passed by Congress in the wake of the Exxon Valdez disaster, the act creates a National Contingency Plan that gives OSHA inspection authority after a spill and a seat on national and regional response teams. However, the plan simply states that response actions should comply with OSHA standards—but doesn’t set out any clear way to ensure the law is followed. As a consequence, the Center found, too few cleanup workers were given adequate training on the use of personal protective equipment.

Consider, for example, respirators. “When cleanup crews first got to work on the beaches and on the water, there was no carefully considered plan for what protections they needed for the oil fumes and heat,” says CPR President Rena Steinzor, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law.

Denied Protection

But a lack of training about how to use protective gear wasn’t the only problem: In some cases, BP failed to even make gear available.

Kellie Fellows was one of hundreds of workers hired by BP to help clean up beaches in Mississippi last summer, and she later shared her story about her experience with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN). During training Fellows and her co-workers were told that safety was a priority and that they would be provided with respirators and other protective gear.

But when it was time to go to work, there were no respirators provided—even though there was a strong smell of oil on the beach. Initially they were given Tyvek protective suits to wear but were instructed to pull them up only partway and to tie the arms around their waists.

Eventually they were told there was no danger—and instead of suits, they were only given straw hats, safety glasses and gloves and sent to work.

Fellows’ job was to hold a trash bag while two men shoveled in tar balls and to tie off the bag in a knot, a task that caused her bare arms to repeatedly touch the oil-smeared bag. Eventually her arms became covered with oil, which also worked its way down inside her gloves. Her skin began burning.

“I wanted to be in a Tyvek [suit],” she told LEAN. “And they refused.”

When she reported the contamination to her superiors at BP, no one seemed to know what to do. They ended up washing her hands with soap and bottled water, rubbing on a couple packets of burn cream, and sending her home for the rest of the day.

Fellows has been left: with lingering headaches that she attributes to the toxic exposures, and she believes many others are still experiencing health-damaging consequences—even though the managers denied the clean-up had anything to do with it.

“Everyone was given excuses,” Fellows says. “Oh, you have the flu, it’s going around, that kind of thing. Bronchial issues? Oh, well, it’s allergies. Every excuse known to man was given except for them to actually say this is coming from the oil.”

Louis Bayhi, a Louisiana charter boat captain, heard the same story after he was hired by BP to shuttle divers and scientists to the spill site, and later worked for BP’s Vessels of Opportunity program in direct cleanup.

Bayhi says he was told he didn’t have to wear a respirator since he wouldn’t be directly touching the oil, though he says the fumes still sickened him and his crew. Two co-workers passed out on his boat, were taken for emergency treatment, and never returned. He still doesn’t know what happened to them.

When crews would arrive back at shore, Bayhi says, BP medical staff would ask them how they were feeling. When they described headaches and other problems, they were told they must be seasick.

“I’ve been offshore pretty much all my life and I got sick one time because I ate Froot Loops and beer for breakfast,” he said in a speech recorded by LEAN. “Other than that, I really don’t remember a time I got seasick.”

Seasickness doesn’t continue onshore for months on end—but Bayhi’s symptoms have. In April 2011, he spent five days in the hospital with severe abdominal pain. The doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him, but he suspects it was related to his oil exposure.

Environmental health advocates say the kind of exposures cleanup workers suffered is unthinkable in this day and age.

“The workplace environment cleanup people were put in was totally unacceptable for 2010,” Wilma Subra, an environmental chemist who works with LEAN, told Southern Exposure. “You had a responsible party with resources, and it should not have happened.”

“Human Health Hazards: Acute”

Adding to the toxic stew in the Gulf—and the health risks to cleanup workers and coastal residents—was BP’s government-approved plan to disperse massive oil slicks after the spill.

Oil dispersants are a mix of surfactants and industrial solvents that cause oil to form into droplets and fall to the ocean floor. Less than a month after the Deepwater Horizon explosion, BP reported spraying more than 400,000 gallons of dispersant on the slick and wellhead itself—primarily two versions of Corexit, manufactured by Illinois-based Nalco.

Corexit EC9500A and Corexit EC9527A were both on the list of 18 dispersants approved for use on oil spills by the Environmental Protection Agency. However, as The New York Times reported in a May 2010 story titled “Less Toxic Dispersants Lose Out in BP Oil Spill Cleanup,” the EPA’s own data showed that Corexit was far more toxic—and far less effective— than other alternatives in handling southern Louisiana crude:

Of 18 dispersants whose use EPA has approved, 12 were found to be more effective on southern Louisiana crude than Corexit, EPA data show. Two of the 12 were found to be 100 percent effective on Gulf of Mexico crude, while the two Corexit products rated 56 percent and 63 percent effective, respectively. The toxicity of the 12 was shown to be either comparable to the Corexit line or, in some cases, 10 or 20 times less, according to EPA.

Considered a trade secret, the precise contents of dispersants like Corexit were initially hidden from public view and only revealed to the Environmental Protection Agency in June 2010 after extensive negotiations. However, OSHA requires that any ingredients which may be harmful to exposed workers be listed on readily available Material Safety Data Sheets. For both forms of Corexit used by BP—Corexit EC9500A and EC9527A—the data sheets include this warning: “Human health hazards: acute.”

OSHA’s data sheet for Corexit EC9527A details the potential health consequences: “[E]xcessive exposure may cause central nervous system effects, nausea, vomiting, anesthetic or narcotic effects.” It also notes that this version of Corexit includes 2-butoxyethanol, stating that “repeated or excessive exposure to butoxyethanol may cause injury to red blood cells (hemolysis), kidney or the liver. . . . Prolonged and/or repeated exposure through inhalation or extensive skin contact with EGBE [butoxyethanol] may result in damage to the blood and kidneys.”

By September 2010, BP reported spraying about 2 million gallons of dispersants for the Deepwater Horizon spill—an unprecedented amount. And some Gulf scientists believe there is already strong evidence that it is having adverse health impacts.

In July 2010, Dr. Susan Shaw, founder and director of the Marine Environmental Research Institute in Maine, appeared on a special CNN report to tell about a shrimper whose skin had been splashed with Gulfwater:

. . . [H]e got a headache that lasted for three weeks. He had heart palpitations. He had muscle spasms and . . . bleeding from the rectum.

And that’s what Corexit does. It ruptures red blood cells, causes internal bleeding, and liver and kidney damage.

This stuff is so toxic combined [with oil] . . . it goes right through skin.

As with the risks of severe oil exposure, the hazards posed by Corexit were already known. The United Kingdom had famously banned the used of the dispersant. A version of Corexit was also used after the Exxon Valdez disaster and implicated by cleanup workers and environmental advocates for the health problems many suffered after that disaster.

Even when faced with growing criticism about the use of such toxic elements on such an untested scale—especially near cleanup workers and coastal communities—government regulators appeared slow to address the hazards.

On May 26, 2010—just over a month after the disaster began—the EPA and U.S. Coast Guard issued a directive telling BP to stop using surface dispersants, except in “rare cases where there may have to be an exception.” Yet as Rep. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) noted in a strongly worded July 30 letter sent to Adm. Thad Allen, the spill recovery commander, exemptions were being routinely granted:

An analysis of the exemption request letters submitted by both the BP and Houma Unified Command, as well as other documents provided to me by the USCG, reveals that since the Directive was issued on May 26th, more than 74 exemption requests have been submitted and, usually within the same day, approved by the USCG. On 5 separate occasions BP submitted requests for pre-authorized exemptions to deviate from EPA and USCG instructions by applying 6,000 gallons of dispersant per day to the ocean surface for an entire week. . . . In every instance this weekly request was approved by the USCG, and on many of these days, BP still used more than double its new 6,000 gallon limit.

The result? Dispersant use declined only 9 percent— even after federal officials had formally directed BP to stop using them in all but the most extreme circumstances.

Aside from the threats posed by immediate exposure, there is concern about the long-term impact of dispersants on the Gulf ecosystem. In May of this year, scientists at the University of West Florida released preliminary findings that, when mixed with oil, Corexit is toxic to phytoplankton and bacteria, the foundation of the food chain—and they said the toxic effect may “cascade” up the chain to larger organisms. The findings of their study, which was funded by BP, also contradicted the company’s claim that dispersants speed up the breakdown of oil by naturally occurring bacteria.

Meanwhile, there have been reports that dispersants were still being used long after the spraying was supposed to have stopped.

In August 2010, a month after the Joint Command for the oil spill had announced the end of dispersant spraying, Rocky Kistner with the Natural Resources Defense Council documented the presence of large tanks of Corexit on Gulf beaches. In early 2011, an MSNBC report gave detailed accounts of Gulfresidents who saw dispersants being sprayed long after July, with C-130S spraying within sight of beaches at night.

“I have received hundreds of reports about improper spraying,” says Wilma Subra of the group LEAN. “It was ongoing, and people are being made very, very sick.”

Subra says she has passed the reports she’s received about the spraying to the EPA. However, the agency has refused to discuss the matter with her, saying only that it’s part of an ongoing criminal investigation.

Just Four Jumbo Shrimp a Week

Another potential health risk for people in the Gulf Coast and beyond is the safety of the region’s seafood.

At a press conference in September 2010, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrator Jane Lubchenco declared that seafood from the Gulf was “free of contamination.” NOAA echoed the sentiment this past April, when it led reporters on a tour of testing facilities in Mississippi and declared that “not one piece of tainted seafood has entered the market” due to the BP spill, according to the Biloxi Sun Herald.

But as Subra points out, test data from the federal government and state agencies contradicted at least the earlier assertions. Twenty-four percent of all Gulf seafood and 43 percent of Gulf oysters sampled through August 2010 contained polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a natural constituent of crude oil and a byproduct of burning fuel. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry reports that PAHs are known to cause cancer, as well as birth defects and damage to the skin and immune system.

While the concentrations detected fell far below the levels of concern established by the Food and Drug Administration, those levels are another source of controversy.

To set its safe consumption levels for Gulf seafood in the wake of the BP oil spill, the FDA measured the levels of PAHs in the seafood against the national average of seafood consumption—about 3 ounces a week. That’s the equivalent of four jumbo shrimp.

But the typical Gulf Coast family—especially in fishing communities—eats much more seafood than that. A survey in late 2010 by the Natural Resources Defense Council of 547 seafood eaters in the Gulf found the median consumption was about 20 seafood meals a month. Those at the higher end consumed up to 60 seafood meals a month. And their portions were bigger than just four jumbo shrimp.

“Those levels are clearly not designed to deal with the situation on the Gulf Coast,” says Subra. “It’s not protective enough.”

What’s more, the estimate is based on the person eating the seafood weighing an average of 176 pounds. What about children? People who weigh less? Pregnant women and their developing fetuses? Federal and state health officials insist their measures are conservative and adequate to protect the public. However, environmental health advocates point out that the FDA itself has applied conflicting standards, using local fish consumption rates to calculate safe limits in the wake of the Exxon Valdez disaster, but switching to less accurate national measures after the BP disaster.

Meanwhile, LEAN has been conducting its own tests of seafood from the Gulf, looking at PAHs as well as total petroleum hydrocarbons, which the FDA is not testing for. LEAN intentionally tested only seafood that appeared pristine and neither looked nor smelled suspicious.

LEAN found that levels of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) in flounder and speckled trout caught in Louisiana’s St. Bernard Parish last August were 21,575 milligrams per kilogram, while oysters caught in Plaquemines Parish showed levels of 12,500 mg/kg. Petroleum levels found in fiddler crabs and periwinkles harvested from Terrebonne Parish on Aug. 19 were 6,916 mg/kg.

Are those levels safe? The federal government does not set acceptable levels for TPHs but instead calculates safe consumption limits for oil components such as benzene and toluene. But Paul Orr ofLEAN says that after talking with researchers and a toxicologist, his group believes that there should be no detectable levels of TPH in seafood.

The prospect of contaminated seafood continues today: At a public meeting held in March 2011 in Grand Isle, La. as part of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment process that’s now underway, shrimpers reported pulling up nets full of oil from the seafloor and facing the decision of whether to report the oil to the Coast Guard, which would mean throwing away the day’s catch, or keeping quiet.

Subra is among those who aren’t taking any chances.

“I don’t eat seafood now from the Gulf or from coastal areas,” she confesses. “I still eat crawfish, but that’s freshwater.”

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.