Poisoned in the Gulf

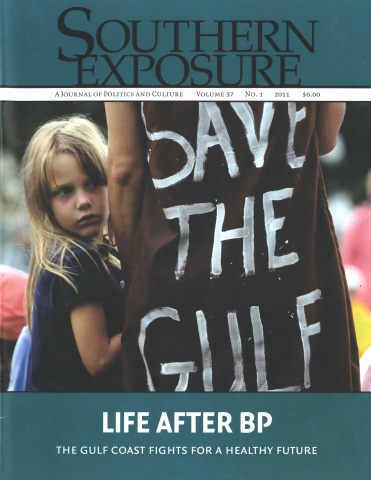

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 37 No. 1, "Life After BP." Find more from that issue here.

Clayton Maherne was just a quarter-mile from BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig when it exploded into flames a year ago in the Gulf of Mexico, killing n workers, injuring 17 others and triggering the largest oil spill in U.S. history.

At the time, Matherne was a boat engineer for Guilbeau Marine, shipping supplies for rig workers. He struggles for words to describe what he witnessed that fateful night.

“It still gives me nightmares today,” he says.

But on April 20, Matherne’s nightmares were just beginning. Two days after the blast, Matherne, a resident of the small town of Lockport in Louisiana’s Lafourche Parish, found himself back at the site of the disaster. BP contracted with Guilbeau Marine to help with the oil cleanup.

Less than an eighth of a mile from where Matherne was skimming oil, other contractors were trying to burn oil off the water’s surface, unleashing massive plumes of black smoke into the air. Meanwhile, low-flying planes dumped chemical dispersants on the growing slick—and directly on Matherne and his fellow cleanup workers.

From the very beginning, Matherne says, he and other workers asked for basic safety equipment like chemical suits and respirators to protect them from the pollution surrounding them. BP refused to provide any.

“So we went and bought our own,” Matherne says. “But BP told us that if we were caught using it, we were fired.”

Almost immediately, Matherne and his fellow workers began experiencing severe headaches and breathing problems. Some workers passed out on the job. Matherne went to the emergency room and was diagnosed with “reactive airway disease secondary to chemical exposure” and sent back to work. Eventually Matherne began vomiting blood. His captain called the BP official overseeing the cleanup operations and told him he feared his employee was dying.

On May 30, 2010, Matherne was airlifted to shore and sent to an emergency clinic, where he says he was diagnosed with acute chemical poisoning. Today his blood still has high levels of dangerous toxins including benzene, arsenic, mercury and xylene—chemicals that commonly show up after exposure to crude oil. He was eventually transferred to a medical center in Houma, La., where he spent five days choking up blood. He was treated with high doses of steroids and released.

Today, Matherne’s lungs are working at only a fraction of their capacity, and he experiences paralyzing headaches. He’s losing control over his bodily functions and faces the possibility of having to wear diapers—a dispiriting prospect for a 35-year-old man who before the BP disaster trained as a power lifter and wrestler and prided himself on his physical strength.

“I can’t even pick up a gallon of milk from the icebox now,” he says. “My wife has to help me put on my shoes.”

“Something I’ve Never Seen”

Matherne’s story is not an unusual one on the Gulf Coast a year after BP’s oil disaster. An investigation by Southern Exposure finds that people across the region from Louisiana to Florida—cleanup workers as well as coastal residents who weren’t directly involved in the cleanup—are reporting unusual health problems that they blame on the oil spill and the chemical dispersants that were used in unprecedented amounts.

Marylee Orr, executive director of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), says she fields a couple of calls a day from people who say they were exposed to BP oil and/or chemical dispersants, and who now report an array of health problems, including respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders, blurred vision, rashes and other skin conditions, bleeding from the rectum and ears, and bloody urine.

Following Hurricane Katrina, Orr’s group assisted cleanup workers who experienced health impacts from exposure to chemicals and pathogens churned up by the storm, but she says those problems pale in scope and severity to what is unfolding now.

“It is something I’ve never seen,” Orr says. “And I’ve been doing this work for 25 years.”

Among the mounting pieces of evidence that the BP spill has unleashed a new set of public health threats in the Gulf:

• Preliminary findings of a coastal survey last August by the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University found that over 40 percent of the population living within 10 miles of the affected coastal areas had experienced direct exposure to the oil spill, and that both adults and children directly exposed to the oil were twice as likely to report new physical or mental health issues as those who were not.

• A door-to-door survey of 954 households conducted across Southeast Louisiana from July through October of last year by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a grassroots environmental nonprofit, found that 46 percent of respondents reported being exposed to oil or dispersant, with 72 percent of those who believed they were exposed reporting at least one associated symptom. Residents reported a sudden onset of symptoms including nausea, dizziness and skin irritation—symptoms common from chemical exposures. •

In early 2011, LEAN released the results of tests performed on blood samples collected from a dozen Gulf residents, fishers and cleanup workers who complained of health problems they believed to be related to the oil spill. All of those tested had high blood levels of ethylbenzene, a component of crude oil that causes respiratory and neurological problems as well as damage to the blood, liver and kidneys. Eleven of those tested had relatively high concentrations of xylenes, a chemical in oil linked to respiratory and neurological problems as well as organ damage, and four showed unusually high levels of benzene, a constituent of oil that is known to cause blood cancer and other serious health problems.

• A team of three scientific divers with the Baton Rouge, La.-based nonprofit EcoRigs who worked in the area near the BP oil spill site last summer report that they began to develop unusual symptoms and by October quit diving, even though they were wearing full wetsuits. However, they have continued to suffer from health problems that include bloody stools, bleeding from the nose and eyes, nausea, diarrhea, stomach cramps, dizziness and confusion. They have had their blood tested, and elevated levels of ethylbenzene and xylene have been discovered.

• A number of people who swam in Gulf waters during the oil spill have since stepped forward to talk about long-term health problems they believe are related to their exposure to the oil and/or chemical dispersants. They include Florida resident Paul Doomm, who was a healthy 22-year-old about to join the Marine Corps when he swam on an open beach off the Florida Panhandle early last summer. By July 2010, he began suffering severe headaches, and by Thanksgiving he was paralyzed on the left side of his body and suffered seizures. He was diagnosed with brain lesions. Meanwhile, Mississippi resident Steven Aguinaga reports that since swimming at Fort Walton Beach in Florida last July he began suffering from chronic chest pain, bloody urine and vomiting. A 33- year-old friend who went swimming with him and then went to work on the BP cleanup also got sick and died suddenly in August.

BP spill-related health problems have also been a leading topic of discussion at various public forums held to discuss the disaster. During a meeting in New Orleans in January to discuss the report released by the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, many Gulf residents described lingering health concerns. Attendees extracted a promise from Commissioner Francis Beinecke of the Natural Resources Defense Council to take their concerns back to the White House. Health concerns also came up repeatedly during a February 2011 meeting of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force in New Orleans.

In March 2011, John Jopling—an attorney with the nonprofit Mississippi Justice Center—attended a town hall meeting in Bay St. Louis, Miss., one of a series organized by state Attorney General Jim Hood.

“We were all blown away by what we heard there,” Jopling reports. “Nothing prepared me for it.”

Jopling expected to hear complaints about BP’s complex and frustrating claims process. Instead, person after person spoke about health problems they attributed to the spill and/or dispersants; some even brought blood test results confirming toxic exposures. Three men told strikingly similar stories about their experiences scouting oil for BP after the spill and then developing a chronic blistering, peeling skin condition on their arms. All said they had difficulty finding a doctor willing to treat them.

Attorney General Hood also seemed surprised. “One of the things that kind of startled me are the people that are concerned about breathing in the fumes, particularly last summer, the effects from it,” Hood later told Mississippi Public Broadcasting. “Many are having effects and there are no doctors here that can really analyze whether it may be as a result of this oil explosion.”

After the March 2011 forum, Hood said he would look into having the state health department or the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do some testing in the area.

A Lack of Options

That a leading Gulf state official was merely considering the possibility of contacting federal health authorities nearly a year after the BP disaster underscores what many see as a breakdown in the government’s public health response to the disaster.

The federal government’s own BP spill commission noted the shortcomings in the ability of current law to address such hazards, recommending that the government be given more power to monitor health impacts. The report also called for long-term tracking of responders’ health and community health in the most affected coastal areas, calling such efforts “warranted and scientifically important.” Indeed, last September the National Institutes of Health announced that it was undertaking a $20 million study looking at potential impacts of the BP spill on cleanup workers.

“However,” the commission report states, “the focus on long-term research cannot overshadow the need to provide immediate medical assistance to affected communities, which have suffered from limited access to healthcare services,” adding that the Gulf’s health care infrastructure was badly damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

The lack of medical options for the BP spill victims is a reality familiar to Clayton Matherne, who—like others in the wake of the disaster—has had a hard time finding a doctor willing to treat him. He says several hung up the phone as soon as he said he got sick doing cleanup work for BP. He figures they didn’t want to get involved because of the possible legal implications.

Eventually he found Dr. Mike Robichaux of Raceland, La., an ear, nose and throat specialist and former state senator who has provided free care for people who believe they have been sickened by the BP spill. Robichaux has put Matherne on high doses of steroids in hopes of keeping his organs from shutting down, and he has referred him to a chemical illness specialist who plans to try detoxification therapy.

If that doesn’t work, the doctors have given Matherne five years to live at most.

Like many others in the Gulf, Matherne has channeled his anger and frustration into advocacy, joining a grassroots movement demanding that officials pay attention to widespread reports of health impacts from the disaster. Matherne is speaking out at public hearings, showing up at press conferences and telling his story to anyone who will listen.

“These companies took my life from me,” Matherne says. “The thing that keeps me going every day is that I’m pissed off.”

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.